Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 17

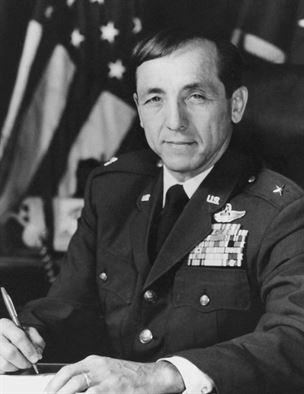

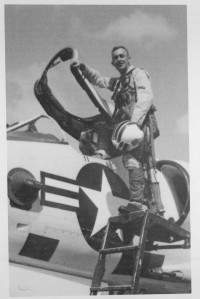

Name: Samuel Robert Johnson

Name: Samuel Robert Johnson

Rank/Branch: O4/United States Air Force

Unit: 433rd TFS

Date of Birth: 11 October 1930

Home City of Record: Dallas TX

Date of Loss: 16 April 1966

Country of Loss: North Vietnam

Status (in 1973): Returnee

Aircraft/Vehicle/Ground: F4C

Missions: 25

NOTE: Flew 62 missions in Korea in F-86’s

Samuel Robert “Sam” Johnson (born October 11, 1930) is a retired career U.S. Air Force officer and fighter pilot and an American politician. He currently is a Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives from the 3rd District of Texas. The district includes much of Collin County, as well as Plano, where he lives.

Johnson grew up in Dallas and graduated from Woodrow Wilson High School. Johnson graduated from Southern Methodist University in his hometown in 1951, with a degree in business administration. While at SMU, Johnson joined the Delta Chi social fraternity as well as the Alpha Kappa Psi business fraternity. He served a 29-year career in the United States Air Force, where he served as director of the Air Force Fighter Weapons School and flew the F-100 Super Sabre with the Air Force Thunderbirds precision flying demonstration team. He commanded the 31st Tactical Fighter Wing at Homestead AFB, Florida and an air division at Holloman AFB, New Mexico, retiring as a Colonel.

He is a veteran of both the Korean and Vietnam Wars as a fighter pilot. During the Korean War, he flew 62 combat missions in the F-86 Sabre. During the Vietnam War, Johnson flew the F-4 Phantom II.

In 1966, while flying his 25th combat mission in Vietnam, he was shot down over North Vietnam. He was a prisoner of war for seven years, including 42 months in solitary confinement. During this period, he was repeatedly tortured.

Johnson was part of a group of 12 prisoners known as the Alcatraz Gang, a group of prisoners separated from other captives for their resistance to their captors. They were held in “Alcatraz”, a special facility about one mile away from the Hỏa Lò Prison, notably nicknamed the “Hanoi Hilton”. Johnson, like the others, was kept in solitary confinement, locked nightly in irons in a 3-by-9-foot cell with the light on around the clock. Johnson recounted the details of his POW experience in his autobiography, Captive Warriors(available through amazon).

Mr. Johnson states “The nearly seven years that I spent in Hanoi but most especially the more than two years in a camp called Alcatraz engendered a close-knit bond between me and some great Americans. I count these men as true friends and their courage and ideals have brought home vividly to me what America is all about. I can only emphasize that the freedoms that most Americans take for granted are in fact, real and must be preserved. I have returned to a great nation and our sacrifices have been well worth the effort. I pledge to continue to serve and fight to protect the freedoms and ideals that the United States stands for” and he has done so.”

A decorated war hero, Johnson was awarded two Silver Stars, two Legions of Merit, the Distinguished Flying Cross, one Bronze Star with Combat “V” for Valor, two Purple Hearts, four Air Medals, and three Air Force Outstanding Unit Awards. He was also retroactively awarded the Prisoner of War Medal following its establishment in 1985. He walks with a noticeable limp, due to an old war injury.

After his military career, he established a homebuilding business in Plano. He was elected to the Texas House of Representatives in 1984 and was re-elected four times. In 1990, Johnson was inducted into the Woodrow Wilson High School Hall of Fame. In October 2009, the Congressional Medal of Honor Society awarded Johnson the National Patriot Award, the Society’s highest civilian award given to Americans who exemplify patriotism and strive to better the nation.

On May 8, 1991, he was elected to the House in a special election brought about by eight-year incumbent Steve Bartlett’s resignation to become mayor of Dallas. Johnson defeated fellow conservative Republican Thomas Pauken, also of Dallas, 24,004 (52.6 percent) to 21,647 (47.4 percent). Johnson thereafter won a full term in 1992 and has been reelected nine times. The 3rd has been in Republican hands since 1968. The Democrats did not even field a candidate in 1992, 1994, 1998, or 2004.

2004: Johnson ran unopposed by the Democratic Party in his district in the 2004 election. Paul Jenkins, an independent, and James Vessels, a member of the Libertarian Party ran against Johnson. Johnson won overwhelmingly in a highly Republican district. Johnson garnered 86% of the vote (178,099), while Jenkins earned 8% (16,850) and Vessels 6% (13,204).

2006: Johnson ran for re-election in 2006, defeating his opponent Robert Edward Johnson in the Republican primary, 85 to 15 percent. In the general election, Johnson faced Democrat Dan Dodd and Libertarian Christopher J. Claytor. Both Dodd and Claytor are West Point graduates. Dodd served two tours of duty in Vietnam and Claytor served in Operation Southern Watch in Kuwait in 1992. It was only the fourth time that Johnson had faced Democratic opposition. Johnson retained his seat, taking 62.5% of the vote, while Democrat Dodd received 34.9% and Libertarian Claytor received 2.6%. However, this was far less than in years past, when Johnson won by margins of 80 percent or more.

2008: Johnson retained his seat in the House of Representatives by defeating the Democrat Tom Daley and Libertarian nominee Christopher J. Claytor in the 2008 general election. He won with 60 percent of the vote, an unusually low total for such a heavily Republican district.

2010: Johnson won re-election with 66.3% of the vote against Democrat John Lingenfelder (31.3%) and Libertarian Christopher Claytor (2.4%).

2014: Johnson handily won re-nomination to his thirteenth term, twelfth full term, in the U.S. House in the Republican primary held on March 4, 2014. He polled 30,943 votes (80.5 percent); two challengers, Josh Loveless and Harry Pierce, held the remaining combined 19.5 percent of the votes cast.

In the House, Johnson is an ardent conservative. By some views, Johnson had the most conservative record in the House for three consecutive years, opposing pork barrel projects of all kinds, voting for more IRAs and against extending unemployment benefits. The conservative watchdog group Citizens Against Government Waste has consistently rated him as being friendly to taxpayers. Johnson is a signer of Americans for Tax Reform’s Taxpayer Protection Pledge. Johnson is a member of the conservative Republican Study Committee, and joined Dan Burton, Ernest Istook and John Doolittle in re-founding it in 1994 after Newt Gingrich pulled its funding. He alternated as chairman with the other three co-founders from 1994 to 1999, and served as sole chairman from 2000 to 2001.

On the Ways and Means Committee, he was an early advocate and, then, sponsor of the successful repeal in 2000 of the earnings limit for Social Security recipients. He proposed the Good Samaritan Tax Act to permit corporations to take a tax deduction for charitable giving of food. He chairs the Subcommittee on Employer-Employee Relations, where he has encouraged small business owners to expand their pension and benefits for employees. Johnson is a skeptic of calls for increased government regulation related to global warming whenever such government interference would, in his mind, restrict personal liberties or damage economic growth and American competitiveness in the market place. He also opposes calls for government intervention in the name of energy reform if such reform would hamper the market and or place undue burdens on individuals seeking to earn decent wages. He has expressed his belief that the Earth has untapped sources of fuel, and has called for allowing additional drilling for oil in Alaska. Johnson is one of two Vietnam-era POWs still serving in Congress.

Johnson is married to the former Shirley L. Melton, of Dallas. They are parents of three children and ten grandchildren.

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 8

SERVICE:

U.S. Marine Corps 1942-1945

U.S. Army Reserve 1946-1949

Iowa Air National Guard 1949-1951

U.S. Air Force 1951-1977

World War II 1942-1945

Cold War 1945-1977

Korean War 1953

Vietnam War 1967-1973 (POW)

Bud Day was born on February 24, 1925, in Sioux City, Iowa. He enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps on December 10, 1942, and spent 30 months in the South Pacific during World War II before receiving an honorable discharge on November 24, 1945.

After the war, Day joined the U.S. Army Reserve on December 11, 1946, and served until December 10, 1949. He was appointed a 2d Lt in the Iowa Air National Guard on May 17, 1950, and went on active duty in the U.S. Air Force on March 15, 1951.

Lt Day completed pilot training and was awarded his pilot wings at Webb AFB, Texas, in September 1952, and completed All-Weather Interceptor School and Gunnery School in December 1952. He served as an F-84 Thunder jet pilot with the 559th Strategic Fighter Squadron of the 12th Strategic Fighter Wing at Bergstrom AFB, Texas, from February 1953 to August 1955, with deployments to Omisawa, Japan, during this time in support of the Korean War.

His next assignment was as an F-84 and F-100 Super Sabre pilot with the 55th Fighter Bomber Squadron of the 20th Fighter Bomber Wing and later on the wing staff at RAF Wethersfield, England, from August 1955 to June 1959, followed by service as an Assistant Professor of Aerospace Science at the Air Force ROTC detachment at St. Louis University in St. Louis, Missouri, from June 1959 to August 1963. During his service in England, he became the first person ever to live through a no-chute bailout from a jet fighter.

CPT Day attended Armed Forces Staff College for Counterinsurgency Indoctrination training at Norfolk, Virginia, from August 1963 to January 1964, and then served as an Air Force Advisor to the New York Air National Guard at Niagara Falls Municipal Airport, New York, from January 1964 to April 1967.

MAJ Day then deployed to Southeast Asia, serving first as an F-100 Assistant Operations Officer at Tuy Hoa AB, South Vietnam, before organizing and serving as the first commander of the Misty Super FACs at Phu Cat AB, South Vietnam, from June 1967 until he was forced to eject over North Vietnam and was taken as a Prisoner of War on August 26, 1967. He managed to escape from his captors and make it into South Vietnam before being recaptured and taken to Hanoi. After spending 2,028 days in captivity, COL Day was released during Operation Homecoming on March 14, 1973. He was briefly hospitalized to recover from his injuries at March AFB, California, and then received an Air Force Institute of Technology assignment to complete his PhD in Political Science at Arizona State University from August 1973 to July 1974.

His final assignment was as an F-4 Phantom II pilot and Vice Commander of the 33rd Tactical Fighter Wing at Eglin AFB, Florida, from September 1974 until his retirement from the Air Force on December 9, 1977. MISTY 1, Col Bud Day, died on July 27, 2013, and was buried at Barrancas National Cemetery at NAS Pensacola, Florida.

His Medal of Honor Citation reads:

On 26 August 1967, Col. Day was forced to eject from his aircraft over North Vietnam when it was hit by ground fire. His right arm was broken in 3 places, and his left knee was badly sprained. He was immediately captured by hostile forces and taken to a prison camp where he was interrogated and severely tortured. After causing the guards to relax their vigilance, Col. Day escaped into the jungle and began the trek toward South Vietnam. Despite injuries inflicted by fragments of a bomb or rocket, he continued southward surviving only on a few berries and uncooked frogs. He successfully evaded enemy patrols and reached the Ben Hai River, where he encountered U.S. artillery barrages. With the aid of a bamboo log float, Col. Day swam across the river and entered the demilitarized zone. Due to delirium, he lost his sense of direction and wandered aimlessly for several days. After several unsuccessful attempts to signal U.S. aircraft, he was ambushed and recaptured by the Viet Cong, sustaining gunshot wounds to his left hand and thigh. He was returned to the prison from which he had escaped and later was moved to Hanoi after giving his captors false information to questions put before him. Physically, Col. Day was totally debilitated and unable to perform even the simplest task for himself. Despite his many injuries, he continued to offer maximum resistance. His personal bravery in the face of deadly enemy pressure was significant in saving the lives of fellow aviators who were still flying against the enemy. Col. Day’s conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Air Force and reflect great credit upon himself and the U.S. Armed Forces.

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 7

Former U.S. senator Adm. Jeremiah Denton, who died at age 89 on 28 March 2014, was interred at Arlington National Cemetery in a service highlighted by the reading of a letter from George H.W. Bush, the appearance and testimonies of fellow Vietnam POWS and attendance by two U.S. senators and a member of the House who shared time with him at the “Hanoi Hilton,” the infamous torture chamber that Denton defied. He wrote a classic – “When Hell Was in Session” that included accounts of his later service in the U.S. Senate with President Ronald Reagan.

Former U.S. senator Adm. Jeremiah Denton, who died at age 89 on 28 March 2014, was interred at Arlington National Cemetery in a service highlighted by the reading of a letter from George H.W. Bush, the appearance and testimonies of fellow Vietnam POWS and attendance by two U.S. senators and a member of the House who shared time with him at the “Hanoi Hilton,” the infamous torture chamber that Denton defied. He wrote a classic – “When Hell Was in Session” that included accounts of his later service in the U.S. Senate with President Ronald Reagan.

Among those in attendance were Sens. Richard Shelby, R-Ala., and Jeff Sessions, R-Ala.; Rep. Sam Johnson, R-Texas, a fellow POW; and Capt. Red McDaniel, author of “Scars and Stripes” and also a fellow POW at the Hanoi Hilton.

Bush’s written tribute said: “We do have heroes … Adm. Jeremiah Denton … was a hero in the truest sense of the word.”

Denton was laid to rest not far from the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

He survived nearly eight years in captivity in Vietnam, including time in the infamous “Hanoi Hilton” after his Navy A-6A Intruder jet was shot down on a bombing mission in 1965.

Four of those years in incarceration were in solitary confinement where he endured starvation and torture in horrendous conditions.

He tells the story in his book “When Hell Was in Session.”

In 1980, he became the first Republican elected to the U.S. Senate from Alabama since Reconstruction. He was a strong supporter of the traditional family and chaired a subcommittee on internal security and terrorism that focused on communist threats.

Reagan, who relied on him for advice on foreign policy, lauded Denton in his 1982 State of the Union address.

“We don’t have to turn to our history books for heroes. They are all around us. One who sits among you here tonight epitomized that heroism at the end of the longest imprisonment ever inflicted on men of our armed forces,” Reagan said.

“Who will ever forget that night when we waited for the television to bring us the scene of that first plane landing at Clark Field in the Philippines – bringing our POWs home? The plane door opened and Jeremiah Denton came slowly down the ramp. He caught sight of our flag, saluted, and said, ‘God Bless America,’ then thanked us for bringing him home.”

He died in Virginia Beach, Virginia, at Sentara Hospice House, said his son, Jeremiah A. Denton 3rd. He is also survived by his second wife, Mary Belle Bordone, four other sons, William, Donald, James and Michael; two daughters, Madeleine Doak and Mary Beth Hutton; a brother, Leo; 14 grandchildren and six great grandchildren.

In “When Hell Was in Session,” Jeremiah Denton, the senior American officer to serve as a Vietnam POW, tells the amazing story of nearly eight years of abuse, neglect and torture. This historic book takes readers behind the closed doors of the Vietnamese prison to see how the men fought back against all odds and against all kinds of evil. It’s available today at a special price.

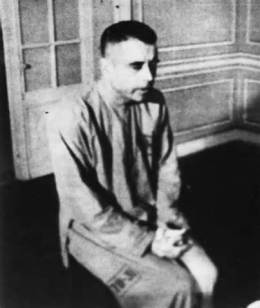

Denton achieved widespread recognition during his imprisonment. In an internationally televised press conference in 1966 staged by the North Vietnamese for propaganda purposes, he answered the interviewer’s questions while simultaneously blinking, in Morse code, the message “T-O-R-T-U-R-E.” The message confirmed to the U.S. for the first time that U.S. POWs were being tortured in captivity.

Further, he shocked his captors when answering questions about what he thought of U.S. actions.

“I don’t know what is going on in the war now because the only sources I have access to are North Vietnam radio, magazine and newspapers, but whatever the position of my government is, I agree with it, I support it, and I will support it as long as I live.”

When he returned on Feb. 12, 1973, he landed at Clark Air Force Base, walked to a waiting microphone and said: “We are honored to have the opportunity to serve our country under difficult circumstances. We are profoundly grateful to our commander-in-chief and to our nation for this day. God bless America.”

He explained how he survived when so many didn’t. “My principal battle with the North Vietnamese was a moral one, and prayer was my prime source of strength,” he said.

The Navy Cross was among the recognitions for his service.

Reagan showed profound respect for Denton.

“Jerry and I came into office in the same year, 1981, and for the last four-and-a-half years, he’s been a pillar of support for our efforts to keep America strong and free and true,” Reagan said. “He’s been rated the most conservative senator by the National Journal. That’s my kind of senator,” Reagan said. “His voting record has been rated 100 percent by the American Conservative Union, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the Conservatives Against Liberal Legislation – I like the name of that one – The National Alliance of Senior Citizens, the Christian Voters Victory Fund, and some others.”

Reagan also noted a poll by the magazine Conservative Digest ranked Denton as the second most admired senator. “Now, knowing Jerry, he’s probably wondering where he slipped up,” Reagan quipped.

His humanitarian work, however, began in his Senate years with the Denton Program, which allowed the U.S. military to haul humanitarian aid on a space-available basis at no cost to the donor. The program now is administered by the U.S. Agency for International Development, the State Department and Defense Department.

His foundation summed up his life in a statement last year.

“It is his belief in, and knowing of God, that is his pillar. This is the central guiding force in his life not only today, but throughout his life,” the foundation said. “Especially in the small, dark jail cell as a POW … for over seven years during the Vietnam war.”

Family man

Born in Mobile, Alabama, on July 15, 1924, his mother and father divorced in 1938. That experience, he said, was one reason why he became such a strong advocate for the nuclear family. ”

He graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1946 and earned a master’s degree in international affairs from George Washington University in 1964.

He married his first wife, the former Kathryn Jane Maury of Mobile, in June 1946, and had seven children with her.

In 2007, they moved from near Mobile to Williamsburg, Virginia, to be closer to some of their children. Mrs. Denton died Nov. 22, 2007, at 81.

His book, “When Hell was in Session,” begins with the shock he experienced upon his return to the United States in 1973 to find his beloved nation had drastically changed since his capture in 1965.

“I saw the appearance of X-rated movies, adult magazines, massage parlors, the proliferation of drugs, promiscuity, pre-marital sex, and unwed mothers.”

That scenario, he wrote, was coupled with “the tumultuous post-war Vietnam political events, starting with Congress forfeiting our military victory, thus betraying our victorious American and allied servicemen and women, who had won the war at great cost of blood and sacrifice.”

Reagan’s ‘amazing lift’

Denton wrote that when he began his Senate service he was not optimistic, recognizing he was “joining a Congress that had voted to sell out the freedom-loving people of South Vietnam, a Congress that voted, in spite of our military victory, to abandon Southeast Asia to the Communists.”

But he received an “an amazing lift” to his “morale and hopes” when President Reagan took him aside to tell him of his great admiration and respect and to invite him to call on him personally if he had anything he believed the president needed to hear.

Denton took up Reagan on his offer, hatching a plan to thwart the rise of communism in Latin American led by Nicaraguan leader Daniel Ortega, who was riding a wave of popularity in U.S. media and academia even as he worked to spread revolution to El Salvador.

Denton secured permission from the State Department to divert a scheduled trip to El Salvador and, instead, fly to Nicaragua to put Ortega’s boasts of freedom and democracy to the test.

Denton described his ambitious venture as a nervy game of single-hand poker with Nicaragua’s leadership. With confidence borne from dealing with “similar people” during his eight years of communist captivity, he held his own, warning Nicaragua’s startled regime, face to face, that any further acts of aggression would be met with a “reaction from the United States under President Reagan different from what you found under President Johnson in North Vietnam.”

Later, Denton found himself in the Oval Office with Reagan, proposing a comprehensive strategy for confronting communism in Latin America that the president accepted and successfully implemented.

‘Misinformation campaign’

Denton observed that since Reagan’s time, “things have not gone as well.”

“One malady continues to worsen: the on-going influence exerted by the misinformation campaign waged by the liberal media/academic community continues to confuse the citizenry,” he wrote.

In an interview in 2009, Denton said one of the problems he saw at the time was the disdain for “ideology” by many of the nation’s most influential leaders and lawmakers. “They are acting like ideology shouldn’t be the point for any discussion of policy,” he said, with energy in his voice belying his 85 years. “[Balderdash!] Ideology is the basis for which you evaluate any policy.”

The most basic principle that distinguishes America as a nation, he said, is the Declaration of Independence’s assertion that all men are created equal and endowed by their creator with inalienable rights. “Nobody is interpreting rights now in terms of the Creator,” he said. “He endowed the rights.”

President Obama, Denton contended, was usurping the rights of God, “as did Hitler and Stalin and the emperors of Rome.”

“They all had gods – but when they didn’t have good enough gods to constitute a culture, they went to hell,” Denton told WND. “And we are too, if we continue to believe that man, all of us individually, or our government, can determine what the rights are and set up everything else to match that. We’re done.”

Denton said he believed the U.S. is in its worst security position since World War II, when Hitler was sweeping across Europe.

He explained that in the aftermath of that war, the U.S. didn’t have to worry as much about its conventional weapons and forces because of its nuclear might and the doctrine of “mutually assured destruction” with the Soviet Union.

But now, he said, with a decreasing percentage of America’s GDP devoted to defense – coupled with China’s and Russia’s buildup of conventional forces – America’s security is at risk.

“If Russia were to take over first Georgia, then Ukraine – and maybe China moves into India – we couldn’t go there with a conventional force and stop that, and we wouldn’t have the guts to use nuclear, for good reason,” he said. Denton said that while the military leaders with whom he spoke agreed with his analysis, President Obama didn’t recognize the problem. “We don’t really have the proper national intelligence the way we used to have,” he said. “We had people like Clare Boothe Luce and brilliant people from many different fields come in, but we don’t do that anymore. It’s done on a haphazard basis.”

Recent Comments