Category Archives: Personal Stories

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 26 – Hall

Virginia Hall was born in Baltimore, Maryland on April 6, 1906. She was the youngest child of Edwin Lee Hall and Barbara Virginia Hammel. Nicknamed “Dindy” by family and friends, Virginia graduated from Roland Park Country Day School in Baltimore. From 1924 to 1926, she attended Radcliffe (Harvard University’s college for women) before going on to Barnard (Columbia University’s college for women). She attended graduate school at the American University in Washington, D.C. A self-confident and outgoing young person, Virginia participated in high school drama productions and was the editor of her college paper and president of her class.

Virginia Hall was born in Baltimore, Maryland on April 6, 1906. She was the youngest child of Edwin Lee Hall and Barbara Virginia Hammel. Nicknamed “Dindy” by family and friends, Virginia graduated from Roland Park Country Day School in Baltimore. From 1924 to 1926, she attended Radcliffe (Harvard University’s college for women) before going on to Barnard (Columbia University’s college for women). She attended graduate school at the American University in Washington, D.C. A self-confident and outgoing young person, Virginia participated in high school drama productions and was the editor of her college paper and president of her class.

She may well have inherited her love of adventure from her father who stowed away on her grandfather’s clipper ship when he was nine. Virginia’s parents took her to Europe for the first time in 1909 and she would go back as often as she could. As a college student, Virginia studied at the Ecole des Sciences Politiques in Paris, the Konsularakademie in Vienna, and completed brief stints at universities in Strasbourg, Grenoble, and Toulouse. While studying in Europe, Virginia mastered both French and German, although she could never quite rid herself of a slight American accent.

Virginia Hall is awarded the Distinguished Service Cross by Bill Donovan, chief of Office of Strategic Services on September 23, 1945. (Photo courtesy: CIA Museum)

Before she ended up at the top of the Gestapo’s most wanted list in Nazi-occupied France, Virginia Hall spent seven years in the U.S. Foreign Service working as a consular clerk in Poland, Turkey, Italy, and Estonia. After she failed to pass the difficult U.S. Foreign Service exam on her first and second tries in December 1929 and July 1930, Virginia decided to get some practical on-the-job experience by working at U.S. missions overseas. As a result, she joined the staff of the U.S. Embassy in Warsaw in July 1931 as a consular clerk. She worked there until April 1933 when she transferred to the U.S. Consulate in the Turkish port city of Smyrna (present day Izmir).

Virginia always had a keen sense of adventure. A great lover of the outdoors, she enjoyed hiking, hunting, and horseback riding. But while serving in Turkey, Virginia suffered an unfortunate hunting accident. On December 8, 1933, her shotgun misfired as she was climbing over a fence, leaving her left foot in tatters. While her colleagues managed to get her to a local hospital in time to save her life, gangrene had already set in. The American doctor who treated her was forced to amputate her left leg below the knee. After her condition stabilized, she transferred to the American Hospital in Istanbul in January 1934. By February, she was able to travel back to the United States to continue treatment. In her home town of Baltimore, Virginia was fitted with a custom prosthetic and started learning how to walk all over again. She named her new leg “Cuthbert.”

By September 1934, Virginia was ready to get back to work. She wrote the U.S. Department of State asking to be reinstated and listed, Spain, Estonia, and Peru as her top three choices for her next assignment. How the small U.S. Legation in Tallinn made it to the top of her bid list is not quite clear. But by the late 1920s, Estonia already had a reputation in U.S. Foreign Service circles as being a very nice place to work. As there were no positions available for consular clerks where she wanted to go, Virginia was offered a position at the U.S. Consulate in Venice instead. By December 1934, she was back at work.

In Venice, Virginia tried once again to pursue her dream of joining the U.S. Foreign Service. But the odds were against her. At that time, only six out of the 1,500 or so commissioned U.S. Foreign Service officers were women. And those six women had to be single. If they got married, regulations required that they resign their commissions. In 1937, Virginia asked to complete the U.S. Foreign Service exam a third time, a process she had begun while stationed in Warsaw. To her great dismay, she received a rejection letter from the U.S. Department of State explaining that regulations required that all applicants be “able-bodied.” Virginia’s amputation, the letter went on to explain, “is a cause for rejection, and it would not be possible for Miss Hall to qualify for entry into the Service under these regulations.”

Stunned, Virginia tried to appeal the decision. Hoping that a change of location might do her some good, Virginia accepted an opening at the U.S. Legation in Tallinn where she arrived in June 1938. Under the supervision of U.S. Consul Walter A. Leonard and Vice Consul Montgomery H. Colladay, Virginia worked once again as a consular clerk. She was in Tallinn on November 24, 1938 when U.S. Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary John C. Wiley presented his credentials to State Elder Konstantin Päts – although Virginia would not have been allowed to attend the ceremony as a simple Foreign Service clerk.

From Tallinn, Virginia launched her final appeal to Assistant Secretary of State G. Howland Shaw requesting a waiver to take the Foreign Service exam. When her appeal was turned down, Virginia decided that it time to leave the U.S. Foreign Service. The routine life of a consular clerk in a nice, quite post like Tallinn simply did not offer enough of a challenge. Virginia resigned from the U.S. Foreign Service and left Estonia for Paris in May 1939 in search of something greater. In France, Virginia would find her true calling, where her twin “handicaps” of being both a woman and an amputee would not matter.

After her dreams of joining the U.S. Foreign Service were crushed, Virginia spent the summer of 1939 in Paris trying to figure out what to do with her life. Hitler’s September 1, 1939 invasion of Poland provided the answer for her. Right after France declared war on Germany on September 3, Virginia decided to follow in Ernest Hemingway’s Great War footsteps by enlisting in the French ambulance corps known as the Services Sanitaires de l’Armee as a private. During the so-called “Phony War” which lasted from September 1939 to May 1940 when the French and Germans fought only minor skirmishes, Virginia received first aid training and began her work as an ambulance driver. The job evacuating casualties from the front lines was not easy, especially as Virginia had to drive an ambulance with her wooden leg. But all hell finally broke loose on May 10 when the Germans turned their full military might on France. From that day until the fall of Paris on June 14, Virginia worked almost around the clock evacuating the wounded to relative safety.

After France surrendered to Nazi Germany on June 22, Virginia found herself stuck in occupied France. Disgusted by the Nazi regime and their policies directed against European Jews, Virginia decided that the best way for her to continue fighting the good fight would be to go to England. Thanks for her U.S. passport; she made her way to London via neutral Spain in August 1940. When she checked in at the U.S. Embassy, Virginia was immediately asked to debrief the staff about the situation in occupied France. In September, she was hired by the U.S. Defense Attaché’s Office. But Virginia did not want to end up right where she started, working as a clerk at a U.S. mission. After surviving the Battle of Britain and the Luftwaffe’s round-the-clock bombings of London which lasted from July to October 1940, Virginia was all the more convinced that she wanted to take the war to the Germans.

On February 26, 1941, Virginia resigned her position at the U.S. Embassy in London as a code clerk stating that she was “seeking other employment.” What Virginia failed to mention is that she had been recruited by the British Special Operations Executive (SOE). After completing the elite SOE’s demanding agent training program, Virginia became an SOE special agent in April 1941. She then spent the summer planning her deployment in Vichy France. Virginia, codenamed Germaine, arrived in France on August 23, 1941 assuming the identity of Brigitte LeContre, a French-American reporter for the New York Post. While the SOE usually kept its agents in the field for just six months, Virginia spent the next fifteen months working in Lyon organizing, funding, supplying, and arming the French resistance. She rescued downed Allied airmen, making sure they made it safely back to England. She oversaw SOE parachute drop, designed to supply resistance fighters. She organized sabotage attacks against German supply lines. She engineered POW escapes from German and Vichy French prisons and camps. She served as a liaison for other SOE agents operating in southern France.

Virginia did her job so well that she came to the attention of both the French Vichy Police and the German Gestapo. Because Virginia was a master of evasion and disguise, they never quite managed to figure out who Germaine was. But the Nazi authorities had enough information on her that they were looking for a “French-Canadian” nicknamed la dame qui boite – the Lady with the Limp. When U.S. and British forces invaded North Africa in November 1942, the fiction that was known as Vichy France came to an abrupt end. German troops took full control of the rest of France. The infamous Klaus Barbie assumed control over the Gestapo in former Vichy territorities. “The Butcher of Lyon” – as he would become known – launched a nation-wide hunt to find Virginia, complete with want ads and posters. The Nazis code-named Virginia Artemis. Barbie is reputed to have told his staff: “I would give anything to lay my hands on that Canadian bitch.”

But by the time Barbie arrived in Lyon, Virginia had vanished. Despite the winter snows and her wooden leg, Virginia hiked all the way across the Pyrenees and into Spain. After being imprisoned in Spain for twenty days for lacking the proper documentation for entry, Virginia made it back to London in time for Christmas dinner where she was greeted by her SOE colleagues as a hero. Not content to sit around, Virginia wanted to get back out into the field.

But now that Virginia was at the top of the Gestapo’s most wanted list, the SOE thought that it was much too dangerous to send her back to occupied France. Virginia’s next assignment took her to Madrid in May 1943 where she worked undercover as a reporter for the Chicago Tribune. Her job was to run a network of safe houses. But Spain was too far from the front lines for Virginia’s liking. She transferred back to London and spent her free time how to become a radio operator. In July 1943, Virginia was made a Member of the British Empire for her outstanding contributions to the Allied war effort. She declined to accept the medal from King George VI for fear it would blow her cover.

As the SOE refused to send her back behind German lines, Virginia set out to find someone who would. On March 10, 1944, Virginia joined the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS) with the grudging approval of the SOE. By the end of the month, Virginia (now code-named Diane) was back in France disguised as an old lady. She was taken to the coast of Bretagne by a wooden speed boat under the cover of darkness. She and a fellow agent landed on the shore in a rubber dinghy. After transiting through Paris, Virginia set up operations in a village south of Paris named Maidou where she monitored and reported on German troop movements. As the Germans had sophisticated radio detection equipment, the job of an undercover radio operator was incredibly dangerous. When the Gestapo began to close in, Virginia moved further south to the town of Cosne where she set up operations in May 1944. With the Allied invasion of France drawing near, OSS agent Diane received new orders to organize the local French Résistance forces. Having already done this in Lyon for the SOE, Virginia knew exactly what to do. She went to work contacting the French Résistance network and arranging for weapons, supplies, and other agents to be dropped behind enemy lines.

By the time Allied troops landed in Normandy on the morning of June 6, 1944, Virginia and her men were ready. They sabotaged supply lines, attacked German troops, and caused enough chaos behind enemy lines to hinder movements to the north of France. All over France, other OSS- and SOE-led French Résistance groups were doing exactly the same. When Allied troops hit the beaches of southern France on August 16, 1944, Virginia and her fellow agents switched tactics. What had been a guerilla war intended to harass and disrupt German forces became an all out war. On August 26, Virginia and her French Résistance troops accepted the surrender of the German southern command at Le Chambon. As the war in France was winding down, Virginia was instructed to coordinate another parachute drop on September 4. One of the men who arrived as part of the drop was a French-American lieutenant named Paul Goillot who called both Paris and New York home. While it was almost love at first sight, there was still a war to be won.

After clearing their zone of any resistance, Virginia, Paul, and several of their colleagues left Cosne on September 13 looking for more Germans to fight. By September 25, they made it to Paris which had been liberated the month before. After they reporting in, the OSS congratulated Virginal and her team on a job well done and pulled them out of the field.

Although it looked like the war would soon be over, the Battle of the Bulge (December 1944 to January 1945) made it clear that the final battle for Germany would be long and hard. As a result, Virginia and Paul volunteered for another dangerous mission, this one behind German lines in Austria. On April 25, Virginia’s new OSS team was in position in Switzerland, waiting for their orders to cross the border. But on May 2, the mission was scrubbed. Six days later, Germany surrendered to the Allies. The war in Europe was finally over.

Already a British hero for her work with the SOE, Virginia became an American hero when she received the Distinguished Service Cross on September 23, 1945 for her work with the OSS. In a letter to President Harry S Truman, General William J. Donovan wrote: “Miss Virginia Hall, an American civilian working for this agency in the European Theatre of Operations, has been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against the enemy. We understand that Miss Hall is the first civilian woman in this war to receive the DSC. Despite the fact that she was well known to the Gestapo, Miss Hall voluntarily returned to France in March 1944 to assist in sabotage operations against the Germans.” Although President Truman wanted to present the award at a public ceremony, Virginia insisted on protecting her cover. So instead, General Donovan – who earned both the Medal of Honor and the DSC while in command of the famous “Fighting Irish” regiment during the First World War – gave Virginia her DSC at a private ceremony attended only by her mother.

Always modest, Virginia’s only comment on receiving America’s second highest award for bravery is said to have been: “Not bad for a girl from Baltimore.”

Back in the United States after the war, Virginia tried to join the U.S. Foreign Service one more time in March 1946 after President Truman dissolved the OSS. But she was turned down once again – this time because of “budgetary cutbacks.” As a result, Virginia ended up joining the recently created Central Intelligence Group which would eventually evolve into the Central Intelligence Agency. Virginia spent a good part of 1947 and 1948 working in the field in Europe. After her return to the U.S., she worked for the CIA’s National Committee for Free Europe in New York City where she lived with her long-time love, Paul Goillot. The two would finally get married in 1950. While Virginia wanted to stay out in the field, the CIA put her to work as an analyst in the Office of Policy Coordination in Washington in December 1951. Working a variety of jobs at the agency, Virginia was the first woman to become a member of the CIA’s Career Staff in 1956. She left ten years later when she reached the mandatory retirement age of sixty.

Living on her farm in Barnestown, Maryland, Virginia enjoyed reading, bird-watching, gardening, weaving, and her pet poodles. She died on July 12, 1982 in Rockville, Maryland at the age of 76. Virginia’s wartime exploits are meticulously documented in Judith L. Pearson’s The Wolves at the Door: the True Story of America’s Greatest Female Spy (2005).

(Resources used for this article come from the following:

Web Sites:

- Central Intelligence Agency

Books:

- Pearson, Judith L.The Wolves at the Door: The True Story of America’s Greatest Female Spy. Lyons Press, 2005.

- Kramer, Ann Women Wartime Spies. MJF Books, Fine Communications, 2011

Works Cited:

- This article is excerpted in part from the “Clandestine Women: The Untold Stories of Women in Espionage” Exhibition, produced by the National Women’s History Museum, Annandale, Virginia, in 2002.

- ”Virginia Hall,” Central Intelligence Agency, n.d., http://www.cia.gov/cia/ciakids/history/vhall.html.

- “We must find and destroy her,” S. News, 27 January 2003

- PHOTO; CIA

Six Little Known Facts about Pearl Harbor and the USS Arizona

December 7, 1941

As we commemorate the 77th anniversary of this “date which will live in infamy,” as President Franklin D. Roosevelt described it on December 8, 1941, explore six little known facts about the USS Arizona and the attack that plunged America into war.

- At 6:54 a. m. (Hawaii Time) The USS Ward sunk a Japanese midget submarine near the entrance to Pearl Harbor.

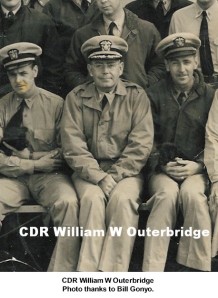

At the beginning of World War II, Captain William Outerbridge skippered the USS Ward, a re-commissioned ship built during the World War I period. Reportedly in his first command and on his first patrol off Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, Outerbridge

beginning of World War II, Captain William Outerbridge skippered the USS Ward, a re-commissioned ship built during the World War I period. Reportedly in his first command and on his first patrol off Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, Outerbridge and the USS Ward detected a Japanese two-man midget submarine near the entrance to Pearl Harbor. The USS Ward detected the midget sub at 6:45 AM and sank it at 6:54 AM, firing the first shots in defense of the U.S. in World War II. Captain Outerbridge was reportedly awarded the Navy Cross for Heroism.

and the USS Ward detected a Japanese two-man midget submarine near the entrance to Pearl Harbor. The USS Ward detected the midget sub at 6:45 AM and sank it at 6:54 AM, firing the first shots in defense of the U.S. in World War II. Captain Outerbridge was reportedly awarded the Navy Cross for Heroism.

(Sub was located 2002 exactly at location in Outerbridge’s report.)

- At 7:55 a.m. (Hawaii Time) – The United States of America was plunged into World War II

At 7:55 a.m. Hawaii time (12:55 p.m. EST) on December 7, 1941, Japanese fighter planes attacked the U.S. base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, launching one of the deadliest attacks in American history. The assault, which lasted less than two hours, claimed the lives of more than 2,500 people, wounded 1,000 more and damaged or destroyed 18 American ships and nearly 300 airplanes. Almost half of the casualties at Pearl Harbor occurred on the naval battleship USS Arizona, which was hit four times by Japanese bombers.

At 7:55 a.m. Hawaii time (12:55 p.m. EST) on December 7, 1941, Japanese fighter planes attacked the U.S. base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, launching one of the deadliest attacks in American history. The assault, which lasted less than two hours, claimed the lives of more than 2,500 people, wounded 1,000 more and damaged or destroyed 18 American ships and nearly 300 airplanes. Almost half of the casualties at Pearl Harbor occurred on the naval battleship USS Arizona, which was hit four times by Japanese bombers.

- Twenty-three sets of brothers died aboard the USS Arizona.

There were 37 confirmed pairs or trios of brothers assigned to the USS Arizona on December 7, 1941. Of these 77 men, 62 were killed, and 23 sets of brothers died. Only one full set of brothers, Kenneth and Russell Warriner, survived the attack; Kenneth was away at flight school in San Diego on that day and Russell was badly wounded but recovered. Both members of the ship’s only father-and-son pair, Thomas Augusta Free and his son William Thomas Free, were killed in action. Though family members often served on the same ship before World War II, U.S. officials attempted to discourage the practice after Pearl Harbor. However, no official regulations were established, and by the end of the war hundreds of brothers had fought—and died,—together. The five Sullivan brothers of Waterloo, Iowa, for instance, jointly enlisted after learning that a friend, Bill Ball, had died aboard the USS Arizona; Their only condition upon enlistment was that they be assigned to the same ship. In November 1942, all five siblings were killed in action when their light cruiser, the USS Juneau, was sunk during the Battle of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands.

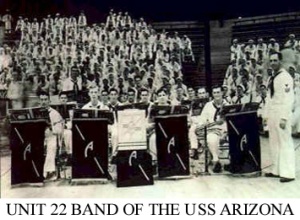

Almost half of the casualties at Pearl Harbor occurred on the naval battleship USS Arizona, which was hit four times by Japanese bombers and eventually sank. Among the 1,177 crewmen killed were all 21 members of the Arizona’s band, known as U.S. Navy Band Unit (NBU) 22. Most of its members were up on deck preparing to play music for the daily flag raising ceremony when the attack began. They instantly moved to man their battle positions beneath the ship’s gun turret. At no other time in American history has an entire military band died in action.

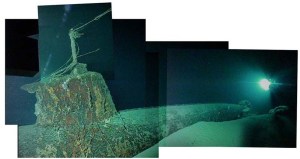

- Fuel continues to leak from the USS Arizona’s wreckage.

December 6, 1941, the USS Arizona took on a full load of fuel—nearly 1.5 million gallons—in preparation for its scheduled trip to the mainland later that month. The next day, much of it fed the explosion and subsequent fires that destroyed the ship following

its attack by Japanese bombers. While the USS Duncan was in at Pearl Harbor for refitting and repairs, Roy Boehm, a 17 year old Navy hardhat diver, was tasked with salvaging the sunken USS Arizona and diving to recover corpses and ammunition. (Boehm would continue in the Navy and eventually be asked by President John F. Kennedy to form the SEALs, thus becoming the First SEAL.)

However, despite the raging fire and ravages of time, some 500,000 gallons are still slowly seeping out of the ship’s submerged wreckage: Nearly 70 years after its demise, the USS Arizona continues to spill up to 9 quarts of oil into the harbor each day. In the mid-1990s, environmental concerns led the National Park Service (NPS) to commission a series of site studies to determine the long-term effects of the oil leakage.

Some scientists have warned of a possible “catastrophic” eruption of oil from the wreckage, which they believe would cause extensive damage to the Hawaiian shoreline and disrupt U.S. naval functions in the area. The NPS and other governmental agencies continue to monitor the deterioration of the wreck site but are reluctant to perform extensive repairs or modifications due to the Arizona’s role as a “war grave.” In fact, the oil that often coats the surface of the water surrounding the ship has added an emotional gravity for many who visit the memorial and is sometimes referred to as the “tears of the Arizona,” or “black tears.”

Some scientists have warned of a possible “catastrophic” eruption of oil from the wreckage, which they believe would cause extensive damage to the Hawaiian shoreline and disrupt U.S. naval functions in the area. The NPS and other governmental agencies continue to monitor the deterioration of the wreck site but are reluctant to perform extensive repairs or modifications due to the Arizona’s role as a “war grave.” In fact, the oil that often coats the surface of the water surrounding the ship has added an emotional gravity for many who visit the memorial and is sometimes referred to as the “tears of the Arizona,” or “black tears.”

- Some former crew-members have chosen the USS Arizona as their final resting place.

The bonds between the crew-members of the USS Arizona have lasted far beyond the ship’s loss on December 7, 1941. Since 1982, the U.S. Navy has allowed survivors of the USS Arizona to be interred in the ship’s wreckage upon their deaths. Following a full military funeral at the Arizona memorial, the cremated remains are placed in an urn and then deposited by divers beneath one of the Arizona’s gun turrets. To date, more than 30 Arizona crewmen who survived Pearl Harbor have chosen the ship as their final resting place. Crew-members who served on the ship prior to the attack may have their ashes scattered above the wreck site, and those who served on other vessels stationed at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, may have their ashes scattered above their former ships. There are 3 living survivors as of today, 02 Dec 2018. Several have decided to be buried on the Arizona.

After the USS Arizona sank, its superstructure and main armament were salvaged and reused to support the war effort, leaving its hull, two gun turrets and the remains of more than 1,000 crewmen submerged in less than 40 feet of water. In 1949 the Pacific War Memorial Commission was established to create a permanent tribute to those who had lost their lives in the attack on Pearl Harbor, but it was not until 1958 that President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed legislation to create a national memorial. The funds to build it came from both the public sector and private donors, including one unlikely source. In March 1961, entertainer Elvis Presley, who had recently finished a two-year stint in the U.S. Army, performed a benefit concert at Pearl Harbor’s Block Arena that raised over $50,000—more than 10 percent of the USS Arizona Memorial’s final cost. The monument was officially dedicated on May 30, 1962, and attracts more than 1 million visitors each year.

Pearl Harbor: Firing the First Defensive Shot

It was at last my senior year in high school. We were so excited to be graduating at the end of this school year. We had several new teachers that year because the school had enlarged. One of the new teachers was a Chemistry teacher named Mr. Outerbridge. None of us knew at the time he would change our lives as he had the lives of many others 30 years prior.

It was at last my senior year in high school. We were so excited to be graduating at the end of this school year. We had several new teachers that year because the school had enlarged. One of the new teachers was a Chemistry teacher named Mr. Outerbridge. None of us knew at the time he would change our lives as he had the lives of many others 30 years prior.

Let me introduce you to Mr. Outerbridge. He was an older gentleman probably about mid 70’s in age. He always had a lot of neat stories to tell when we completed our chemistry lessons for the day. William Woodward Outerbridge was born in Hong Kong, China, on 14 April 1906. He matriculated at MMI from Middleport, Ohio, and graduated from the high school program in 1923. A member of “E” Company, he was a cadet private and held membership in the Yankee Club and, ironically, in the Stonewall Jackson Literary Society. He graduated from the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, MD, in the Class of 1927.

One day in December he told us we would take a break from Chemistry. He needed to tell us a true story about himself and Pearl Harbor. Of course all of us thought we knew all about Pearl Harbor since we have been taught about that since our earliest memories. Little did we know we had a true war hero in our midst. That man was Captain William Woodward Outerbridge, Captain of the USS Ward. The Ward was advised by the USS CONDOR that a mini-sub was headed to the entry channel of the port of Pearl Harbor, Oahu, Hawaii.

At the beginning of World War II, Captain Outerbridge skippered the USS Ward, a recommissioned ship built during the World War I period. Reportedly in his first command and on his first patrol off Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, Outerbridge and the USS Ward detected a Japanese two-man midget submarine near the entrance to Pearl Harbor. The USS Ward detected the midget sub at 6:45 AM and sank it at 6:54 AM, firing the first shots in defense of the U.S. in World War II. Captain Outerbridge was reportedly awarded the Navy Cross for Heroism.

Noted for firing the first shots in defense of the United States during World War II – just prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor – then Captain William W. Outerbridge served as the skipper of the destroyer USS Ward. He reported the action and the sinking of the submarine before the attack by Japan.

During World War II, Captain Outerbridge served in both the Pacific and the Atlantic, taking part in operations at Pearl Harbor, Normandy and Cherbourg, France, and at Ormoc, Mindoro, Lingayon Gulf and Okinawa. He also participated in the carrier task force strikes against Tokyo and the Japanese mainland.

Outerbridge later both attended and taught at the Naval War College; he also taught at the Industrial College of the Armed Forces. William Outerbridge retired from the Navy in 1957 as a Rear Admiral (RADM).

RADM Outerbridge married the former Grace Fulwood of Tifton, Georgia. They were the parents of three sons. The Admiral died on 20 September 1986. His last address was Tifton, Georgia.

In 2002, the submarine was discovered in 1200 feet of water off Pearl Harbor with the shell holes in the coning tower confirmed Outerbridge’s report.

(This information is presented from this author’s personal conversations with RADM Outerbridge, from her notes and from personal research. Additional information may be located in the Eisenhower Library Papers, the USN Archives re: investigation of the sinking of the mini sub.)

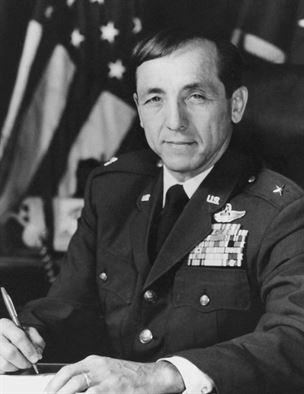

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 21

James Robinson Risner

James Robinson Risner

Nickname(s): Robbie

Born: January 16, 1925; Mammoth Spring, Arkansas

Died: October 22, 2013 (aged 88); Bridgewater, Virginia

Place of burial: Arlington National Cemetery

Allegiance: United States of America

Service/branch: United States Army Air Forces; United States Air Force

Years of service: 1943–1946 1951-1976

Rank: Brigadier General

Commands held: 832d Air Division; 67th Tactical Fighter Squadron; 34th Fighter-Day Squadron; 81st Fighter-Bomber Squadron

Battles/wars: Korean War; Vietnam War

Awards: Air Force Cross (2); Silver Star (2); Distinguished Flying Cross (3); Bronze Star with “V” (2); Air Medal (8); Joint Service Commendation Medal; Purple Heart (4)

James Robinson “Robbie” Risner (January 16, 1925 – October 22, 2013) was a general officer and professional fighter pilot in the United States Air Force.

Risner was a double recipient of the Air Force Cross, the second highest military decoration for valor that can be awarded to a member of the United States Air Force. He was the first living recipient of the medal, awarded the first for valor in aerial combat during the Vietnam War, and the second for gallantry as a prisoner of war of the North Vietnamese for more than seven years.

Commands held: 832d Air Division; 67th Tactical Fighter Squadron; 34th Fighter-Day Squadron; 81st Fighter-Bomber Squadron

Battles/wars: Korean War; Vietnam War

Awards: Air Force Cross (2); Silver Star (2); Distinguished Flying Cross (3); Bronze Star with “V” (2); Air Medal (8); Joint Service Commendation Medal; Purple Heart (4)

Risner became an ace in the Korean War, and commanded a squadron of F-105 Thunderchiefs in the first missions of Operation Rolling Thunder in 1965. He flew a combined 163 combat missions, was shot down twice, and was credited with destroying eight MiG-15s. Risner retired as a brigadier general in 1976.

At his passing, Air Force Chief of Staff General Mark A. Welsh III observed:

“Brig. Gen. James Robinson “Robbie” Risner was part of that legendary group who served in three wars, built an Air Force, and gave us an enduring example of courage and mission success…Today’s Airmen know we stand on the shoulders of giants. One of ‘em is 9 feet tall…and headed west in full afterburner.”

Risner was born in Mammoth Spring, Arkansas on 16 January 1925, but moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1931. His father was originally a sharecropper, then during the Great Depression became a day laborer for the Works Progress Administration. By the time Risner entered high school, his father was self-employed, selling used cars. Risner worked numerous part-time jobs in his youth to help the family, including newspaper delivery, errand boy and soda jerk for a drug store, for the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce at age 16, as a welder, and for his father polishing cars.

Risner had a religious upbringing as a member of the 1st Assembly of God Church. He wrestled for Tulsa Central High School, where he graduated in 1942. In addition to a love of sports, Risner’s interests were primarily in riding horses and motorcycles.

Risner enlisted in the United States Army Air Forces as an aviation cadet in April, 1943, and attended flight training at Williams Field, Arizona, where he was awarded his pilot wings and a commission as 2nd Lieutenant in May 1944. He completed transition training in P-40 Warhawk and P-39 Airacobra fighters before being assigned to the 30th Fighter Squadron in Panama.

The 30th FS was based on a primitive airstrip without permanent facilities at Aguadulce, on the Gulf of Panama. Risner noted to a biographer that his tour under these conditions amounted to as much flying as he desired but a distinct lack of discipline on the ground. When the squadron was relocated to Howard Field in the Panama Canal Zone in January 1945 to transition to P-38 Lightning fighters, its pilots were soon banned from the Officers Club for rowdiness and vandalism.

In 1946, Risner was involved in an off-duty motorcycle accident. While undergoing hospital treatment in the Army, he met his first wife Kathleen Shaw, a nurse from Ware Shoals, South Carolina. Risner and Shaw became engaged on a ship and were discharged and married the next month.

In civilian life, Risner tried a succession of jobs, training as an auto mechanic, operating a gas station, and managing a service garage. He also joined the Oklahoma Air National Guard, becoming an F-51 Mustang pilot. He flew nearly every weekend, and on one occasion, became lost in the fringes of a hurricane on a flight to Brownsville, Texas. Forced to land on a dry lakebed, he found that he was in Mexico and encountered bandits, but successfully flew his Mustang to Brownsville after the storm had passed. He received an unofficial rebuke from the American embassy for flying an armed fighter into the sovereign territory of a foreign nation, but for diplomatic reasons the flight was officially ignored.

Risner was recalled to active duty in February 1951 while assigned to the 185th Tactical Fighter Squadron of the OKANG at Will Rogers Field in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. He subsequently received training in the F-80 Shooting Star at Shaw Air Force Base, South Carolina.

Risner’s determination to be assigned to a combat unit was nearly ended when on his last day before going overseas he broke his hand and wrist falling from a horse. Robinson deliberately concealed the injury, which would have grounded him, until able to convince a flight surgeon that the injury had healed. He actually had his cast removed to fly his first mission.

Risner arrived in Korea on May 10, 1952, assigned to the 15th Reconnaissance Squadron at Kimpo Air Base. In June, when the 336th Fighter-Interceptor  Squadron, also at Kimpo, sought experienced pilots, he arranged a transfer to 4th Fighter Wing through the intervention of a former OKANG associate. Risner was often assigned to fly F-86E-10, AF serial no. 51-2824, nicknamed Ohio Mike and bearing a large cartoon rendition of Bugs Bunny as nose art, in which he achieved most of his aerial victories.

Squadron, also at Kimpo, sought experienced pilots, he arranged a transfer to 4th Fighter Wing through the intervention of a former OKANG associate. Risner was often assigned to fly F-86E-10, AF serial no. 51-2824, nicknamed Ohio Mike and bearing a large cartoon rendition of Bugs Bunny as nose art, in which he achieved most of his aerial victories.

His first two months of combat saw little contact with MiGs, and although a flight leader, he took a three-day leave to Japan in early August. The day after his arrival he returned to Korea when he learned that MiGs were operational. Arriving at Kimpo in the middle of the night, he joined his flight which was on alert status. The flight of four F-86 Sabres launched and encountered 14 MiG-15s. In a brief dogfight Risner shot down one to score his first aerial victory on August 5, 1952.

On September 15, Risner’s flight escorted F-84 Thunderjet fighter-bombers attacking a chemical plant on the Yalu River near the East China Sea. During their defense of the bombers, Risner’s flight overflew the MiG base at Antung Airfield, China. Fighting one MiG at nearly supersonic speeds at ground level, Risner pursued it down a dry riverbed and across low hills to an airfield 35 miles inside China. Scoring numerous hits on the MiG, shooting off its canopy, and setting it on fire, Risner chased it between hangars of the Communist airbase, where he shot it down into parked fighters.

On the return flight, Risner’s wingman, 1st Lt. Joseph Logan, was struck in his fuel tanks by anti-aircraft fire over Antung. In an effort to help him reach Kimpo, Risner attempted to push Logan’s aircraft by having him shut down his engine and inserting the nose of his own jet into the tailpipe of Logan’s, an unprecedented and untried maneuver. The object of the maneuver was to push Logan’s aircraft to the island of off the North Korean coast, where the Air Force maintained a helicopter rescue detachment. Jet fuel and hydraulic fluid spewed out from the damaged Sabre onto Risner’s canopy, obscuring his vision, and turbulence kept separating the two jets. Risner was able to re-establish contact and guide the powerless plane out over the sea until fluids threatened to stall his own engine. Near Cho Do, Logan bailed out after calling to Risner, “I’ll see you at the base tonight.” Although Logan came down close to shore and was a strong swimmer, he became entangled in his parachute shrouds and drowned. Risner shut down his own engine in an attempt to save fuel, but eventually his engine flamed out and he glided to a deadstick landing at Kimpo.

On September 21 he shot down his fifth MiG, becoming the 20th jet ace. In October 1952 Risner was promoted to major and named operations officer of the 336th FIS. Risner flew 108 missions in Korea and was credited with the destruction of eight MiG-15s, his final victory occurring January 21, 1953.

Risner was commissioned into the Regular Air Force and assigned to the 50th Fighter-Bomber Wing at Clovis Air Force Base, New Mexico, in March 1953, where he became operations officer of the 81st Fighter Bomber Squadron. He flew F-86s with the 50th Wing to activate Hahn Air Base, West Germany, where he became commander of the 81st FBS in November 1954.

In July 1956, he was transferred to George Air Force Base, California as operations officer of the 413th Fighter Wing. Subsequently he served as commander of the 34th Fighter-Day Squadron, also at George Air Force Base.

During his tour of duty at George Air Force Base, Risner was selected to fly the Charles A. Lindbergh Commemoration Flight from New York to Paris. Ferrying a two-seat F-100F Super Sabre nicknamed Spirit of St. Louis II to Europe on the same route as Lindbergh, he set a transatlantic speed record, covering the distance in 6 hours and 37 minutes.

From August 1960 to July 1961, he attended the Air War College at Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama. He next served on the joint staff of Commander-in-Chief, Pacific (CINCPAC) in Hawaii.

In August 1964, Lieutenant Colonel Risner took command of the 67th Tactical Fighter Squadron, an F-105D Thunderchief fighter-bomber unit based at Kadena AB, Okinawa, and part of the 18th Tactical Fighter Wing. The following January he led a detachment of seven aircraft to Da Nang Air Base to fly combat strikes that included a mission in Laos on January 13 in which he and his pilots were decorated for destroying a bridge, but Risner was also verbally reprimanded for losing an aircraft while bombing a second bridge not authorized by his orders. On February 18, 1965, as part of an escalation in air attacks directed by President Lyndon B. Johnson that resulted in the commencement of Operation Rolling Thunder, the 67th TFS began a tour of temporary duty at Korat RTAFB, Thailand, under the control of the 2d Air Division.

Risner’s squadron led the first Rolling Thunder strike on March 2, bombing an ammunition dump at Xom Biang approximately ten miles north of the Demilitarized Zone. The strike force consisted of more than 100 F-105, F-100, and B-57 aircraft, and in the congested airspace, heavy anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) fire seriously disrupted its coordination and radio communications. Risner’s squadron was tasked with flak suppression, dropping CBU-2 “cluster bombs” from extremely low altitude. His wingman Capt. Robert V. “Boris” Baird was shot down on the opening pass, and the mission was in danger of collapsing when Risner took charge. After the last strike had been delivered, Risner and the two surviving members of his flight remained in the area, directing the search and rescue mission for Baird until their fuel ran low. Risner, in a battle damaged aircraft, diverted to Da Nang air base for landing.

On March 22, 1965, while leading two flights of F-105s attacking a radar site near Vinh Son, North Vietnam, Risner was hit by ground fire when he circled back over the target. He maneuvered his aircraft over the Gulf of Tonkin, ejected a mile offshore, and was rescued after fifteen minutes in the water.

On April 3 and 4, 1965, Risner led two large missions against the Thanh Hóa Bridge in North Vietnam. On the afternoon of April 3, the strike package of Rolling Thunder Mission 9 Alpha consisted of 79 aircraft, including 46 F-105s. 16 of those carried AGM-12 Bullpup missiles, while another 30 carried eight 750-pound bombs each, half of which were designated for the railroad and highway bridge. The force had clear conditions but encountered a severe glare in the target area that made the bridge difficult to acquire for attacks with the Bullpups. Only one Bullpup could be guided at a time, and on his second pass, Risner’s aircraft took a hit just as the missile struck the bridge. Fighting a serious fuel leak and a smoke-filled cockpit in addition to anti-aircraft fire from the ground, he again nursed his crippled aircraft to DaNang. The use of Bullpups against the bridge had been completely ineffectual, resulting in the scheduling of a second mission the next day with 48 F-105s attacking the bridge without destroying it. The missions saw the first interception of U.S. aircraft by North Vietnamese MiG-17 fighters, resulting in the loss of two F-105s and pilots of the last flight, struck by a hit-and-run attack while waiting for their run at the target.

Risner’s exploits earned him an awarding of the Air Force Cross and resulted in his being featured as the cover portrait of the April 23, 1965 issue of Time magazine. The 67th TFS ended its first deployment to Korat on April 26 but returned from Okinawa on August 16 for a second tour of combat duty over North Vietnam.

On August 12, 1965, U.S. Air Force and Navy air units received authorization to attack surface-to-air missile sites supplied to the North Vietnamese by the Soviet Union. Initial attempts to locate and destroy the SA-2 Guideline sites, known as Iron Hand missions, were both unsuccessful and costly. Tactics were revised in which “Hunter-Killer Teams” were created. Employed at low altitudes, the “hunters” located the missiles and attacked their radar control vans with canisters of napalm, both to knock out the SAM’s missile guidance and to mark the target for the “killers”, which followed up the initial attack using 750-pound bombs to destroy the site.

On 16 September 1965 Risner was flying this aircraft when he was shot down by anti-aircraft artillery.

On the morning of September 16, 1965, on an Iron Hand sortie, Risner scheduled himself for the mission as the “hunter” element of a Hunter-Killer Team searching for a SAM site in the vicinity of Tuong Loc, 80 miles south of Hanoi and 10 miles northeast of the Thanh Hoa Bridge. Risner’s aircraft was at very low altitude flying at approximately 600 mph, approaching a site that was likely a decoy luring aircraft into a concentration of AAA. Heavy ground fire struck Risner’s F-105 in its air intakes when he popped up over a hill to make his attack. Again he attempted to fly to the Gulf of Tonkin, but ejected when the aircraft, on fire, pitched up out of control. He was captured by North Vietnamese while still trying to extricate himself from his parachute. He was on his 55th combat mission at the time.

On the morning of September 16, 1965, on an Iron Hand sortie, Risner scheduled himself for the mission as the “hunter” element of a Hunter-Killer Team searching for a SAM site in the vicinity of Tuong Loc, 80 miles south of Hanoi and 10 miles northeast of the Thanh Hoa Bridge. Risner’s aircraft was at very low altitude flying at approximately 600 mph, approaching a site that was likely a decoy luring aircraft into a concentration of AAA. Heavy ground fire struck Risner’s F-105 in its air intakes when he popped up over a hill to make his attack. Again he attempted to fly to the Gulf of Tonkin, but ejected when the aircraft, on fire, pitched up out of control. He was captured by North Vietnamese while still trying to extricate himself from his parachute. He was on his 55th combat mission at the time.

“We were lucky to have Risner. With (Captain James) Stockdale we had wisdom. With Risner we had spirituality.”Commander Everett Alvarez, Jr. – 1st U.S. pilot held as a Prisoner of War in Southeast Asia

After several days of travel on foot and by truck, Risner was imprisoned in Hỏa Lò Prison, known as the Hanoi Hilton to American POWs. However after two weeks he was moved to Cu Loc Prison, known as “The Zoo”, where he was confronted during interrogations with his Time magazine cover and told that his capture had been highly coveted by the North Vietnamese. Returned to Hỏa Lò Prison as punishment for disseminating behavior guidelines to the POWs under his nominal command, Risner was severely tortured for 32 days, culminating in his coerced signing of an apologetic confession for war crimes.

Risner spent more than three years in solitary confinement. Even so, as the officer of rank with the responsibility of maintaining order, from 1965 to 1973 he helped lead American resistance in the North Vietnamese prison complex through the use of improvised messaging techniques (“tap code”), endearing himself to fellow prisoners with his faith and optimism. It was largely thanks to the leadership of Risner and his Navy counterpart, Commander (later Vice Admiral) James Stockdale, that the POWs organized themselves to present maximum resistance. While held prisoner in Hỏa Lò, Risner served first as Senior Ranking Officer and later as Vice Commander of the provisional 4th Allied Prisoner of War Wing. He was a POW for seven years, four months, and 27 days. His five sons had been aged 16 to 3 when he last saw them.

His story of being imprisoned drew wide acclaim after that war’s end. His autobiography, The Passing of the Night: My Seven Years as a Prisoner of the North Vietnamese, describes seven years of torture and mistreatment by the North Vietnamese. In his book, Risner attributes faith in God and prayer as being instrumental to his surviving the Hanoi prison experience. In his words he describes how he survived a torture session in July 1967, handcuffed and in stocks after destroying two pictures of his family to prevent them from being used as propaganda by an East German film crew:

“To make it, I prayed by the hour. It was automatic, almost subconscious. I did not ask God to take me out of it. I prayed he would give me strength to endure it. When it would get so bad that I did not think I could stand it, I would ask God to ease it and somehow I would make it. He kept me.”

Publication of Risner’s book led to a flap with American author and Vietnam war critic Mary McCarthy in 1974. The two had met, apparently at McCarthy’s request, when McCarthy visited Hanoi in April 1968. The meeting, described as “stilted”, resulted in an unflattering portrait of McCarthy in Risner’s book, primarily because she failed to note scars and other evidence of torture he had made plain to her. After publication of the book, McCarthy strenuously attacked both Risner (deeming him “unlikeable” and alleging that he had “become a Vietnamese toady”) and Risner’s credibility in a review. Risner made no rebuttal at the time, but when interviewed by Frances Kiernan decades later, Risner described the review as “character assassination”, a criticism of McCarthy’s treatment supported by several of her liberal peers including Kiernan.”

Risner was promoted to colonel after his capture, with a date of rank of November 11, 1965. He was part of the first group of prisoners released in Operation Homecoming on 12 February 1973 and returned to the United States. In July 1973 USAF assigned him to the 1st Tactical Fighter Wing at MacDill Air Force Base, Florida, where he became combat ready in the F-4 Phantom II. Risner was later transferred to Cannon Air Force Base, New Mexico in February 1974 to command the 832d Air Division, in which he flew the F-111 Aardvark fighter-bomber. He was promoted to brigadier general in May 1974. On 1 August 1975, he became Vice Commander of the USAF Tactical Fighter Weapons Center at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada and retired from the Air Force on 1 August 1976.

Risner’s family life during and following his imprisonment was marked by several personal tragedies. His mother and brother died while he was still a P.O.W. and his oldest son Robbie Jr. died two years after his return of a congenital heart defect. In June 1975 Risner was divorced from his wife Kathleen after 29 years of marriage. In 1976 he met his second wife Dorothy Marie (“Dot”) Williams, widow of a fighter pilot missing-in-action in 1967 and subsequently married her after her missing husband was declared dead. They remained married until the end of his life, with the two younger of his four surviving sons choosing to live with him and Risner adopting her three youngest children. After retirement he lived in Austin, Texas, where he worked with the D.A.R.E. program and raised quarter horses, and later in San Antonio. He later moved to Bridgewater, Virginia.

Risner is one of only four airmen with multiple awards of the Air Force Cross, a combat decoration second only to the Medal of Honor.

The USAF Weapons School Robbie Risner Award, created September 24, 1976, was donated by H. Ross Perot as a tribute to Risner and all Vietnam era Prisoners of War, and is administered by the Tactical Air Command (now by Air Combat Command). The award is presented annually to the outstanding graduate of the USAF Weapons School. The Risner Award is a six and one-half foot trophy consisting of a sculpture of Risner in flight suit and helmet on a marble base, weighing approximately four tons. The trophy is permanently displayed at the United States Air Force Academy, with each winner’s name inscribed. A miniature replica, also donated by Perot, is presented to each year’s recipient as a personal memento. An identical casting, measuring four feet and weighing 300 pounds, was installed in the foyer of the USAF Weapons School at Nellis Air Force Base in October 1984.

A nine foot bronze statue of Risner, sculpted by Lawrence M. Ludtke and mounted on a five foot pedestal of black granite, was commissioned by Perot and dedicated in the Air Gardens at the Air Force Academy on November 16, 2001. In addition to replicating the Risner Award, the statue commemorates Risner and other POWs who were punished for holding religious services in their room at the Hanoi Hilton on February 7, 1971, in defiance of North Vietnamese authorities. The statue was made nine feet tall in memory of Risner’s statement, commenting on his comrades singing The Star Spangled Banner and God Bless America, that “I felt like I was nine feet tall and could go bear hunting with a switch.”

Perot helped Risner later become the Executive Director of the Texans’ War on Drugs, and Risner was subsequently appointed by President Ronald Reagan as a United States Delegate to the fortieth session of the United Nations General Assembly. He was also inducted into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame in November 1974 in recognition of his military service, and announced as an inductee into the Arkansas Military Veterans Hall of Fame on November 1, 2013.

On October 19, 2012, ground was broken at the Air Force Academy for its new Center for Character and Leadership Development. In February 2012 the Academy received a $3.5 million gift from The Perot Foundation to endow the General James R. Risner Senior Military Scholar at the center, who “will conduct research to advance the understanding, study and practice of the profession of arms, advise senior Academy leadership on the subject, and lead seminars, curriculum development, and classroom activities at the Academy.”

The chapter squadron of the Arnold Air Society for Southern California, based on the AFROTC detachment of California State University, San Bernardino, is named for Risner.

Risner died in his sleep October 22, 2013, at his home in Bridgewater, Virginia three days after suffering a severe stroke. Risner was buried at Arlington National Cemetery on January 23, 2014. He was eulogized by Perot and General Welsh with fellow former POWs and current members of the 336th Fighter Squadron among those in attendance.

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 19

Name: Robert Harper Shumaker

Name: Robert Harper Shumaker

Rank/Branch: O4/US Navy

Unit: Fighter Squadron 154

Date of Birth: 11 May 1933

Home City of Record: La Jolla CA (USN says New Wilmington PA)

Date of Loss: 11 February 1965

Country of Loss: North Vietnam

Status (in 1973): Released POW

Aircraft/Vehicle/Ground: F8D

Born in New Castle, PA, on 11 May 1933 to Alva and Eleanor Shumaker, Rear Admiral Robert Shumaker ’56, USN (Ret.), grew up attending local public schools and spent a year at Northwestern University before entering the Naval Academy. Following graduation, he completed flight training and flew the F-8 Crusader with fighter squadron VF-32. Around this time, Shumaker was considered for astronaut training by NASA, but unfortunately his selection was blocked due to a short-term physical ailment.

By early January, 1965, following two significant military defeats at the hands of North Vietnamese guerrilla forces, the Army of the Republic of South Vietnam was near collapse; U.S. options were either to leave the country or increase its military activity. President Johnson chose to escalate. Plans were authorized for a “limited war” that included a bombing campaign in North Vietnam.

The first major air strike over North Vietnam took place in reaction to Viet Cong mortaring of an American advisor’s compound at Pleiku on February 7, 1965. Eight Americans died in the attack, more than one hundred were wounded, and ten aircraft were destroyed. President Johnson immediately launched FLAMING DART I, a strike against the Vit Thu Lu staging area, fifteen miles inland and five miles north of the demilitarized zone (DMZ).

Thirty-four aircraft launched from the USS RANGER, but were prevented from carrying out that attack by poor weather, and the RANGER aircraft were not allowed to join the forty-nine planes from the USS CORAL SEA and USS HANCOCK, which struck the North Vietnamese army barracks and port facilities at Dong Hoi. The strike was judged at best an inadequate reprisal. It accounted for sixteen destroyed buildings. The cost? The loss of one A4E Skyhawk pilot from the USS CORAL SEA and eight damaged aircraft.

FLAMING DART II unfolded 11 February 1965 after the Viet Cong blew up a U.S. enlisted men’s billet at Qui Nhon, killing twenty-three men and wounded twenty-one others. Nearly one hundred aircraft from the carriers RANGER, HANCOCK and CORAL SEA bombed and strafed enemy barracks at Chanh Hoa. Damage assessments revealed twenty-three of the seventy-six buildings in the camp were damaged or destroyed. One American pilot was shot down — LCDR Robert H. Shumaker.

LCDR Robert Shumaker was flying an F-8-D Crusader (assigned to Fighter Squadron 154 on board the USS Coral Sea) when he was hit by 37 mm. cannon fire, which forced the jet out of control. He ejected and his parachute opened a mere 35 feet from the ground. The impact broke his back and he was captured immediately, placed in a jeep and transported over the rutted roads to Hanoi. Upon arrival in Hanoi a white smocked North Vietnamese gave him a cursory examination before dozens of photographers, yet did not give him any medical attention. His back healed itself, but it was six months before he could bend.

Shumaker was the second Navy aviator to be captured. For the next 8 years, Shumaker was held in various prisoner of war camps, including the infamous Hoa Lo complex in Hanoi. Shumaker, in fact, dubbed this complex the “Hanoi Hilton”.

Shumaker, as a prisoner, was known for devising all sorts of communications systems and never getting caught. Like other POWs, he was badgered to write a request for amnesty from Ho Chi Minh, which he refused to do. As punishment, the Vietnamese forced Shumaker to stay in a cell with no heat and no blankets during the winter.

In the torture sessions he continued to hold out for his beliefs. His back healed, but was reinjured two years later in a torture session because he refused to play the part of a wounded American in a propaganda movie. After beating him they used him for the part anyway.

He was known as one of the “Alcatraz Eleven” because he spent nearly three years in solitary confinement, much of the time clamped in leg irons. He would often think of his young son, Grant, who was just a baby when he was shot down. That little boy was eight years old when he saw him again.

As stated previously, Commander Shumaker originated the name “Hanoi Hilton” for the prison. The famous name was the ultimate in satire since the prisoners were tortured, starved and insulted rather than treated with hospitality. Through his entire imprisonment of over eight years, CDR Shumaker maintained himself as a military man. He states that “When we were released, we marched to the airplanes to show we were still a military organization.”

Shumaker was released in Operation Homecoming on February 12, 1973. He had been promoted to the rank of Commander during his captivity. Upon arrival at Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines, CDR Shumaker stated: “I simply want to say that I am happy to be home and so grateful to a nation that never did forget us. We tried to conduct ourselves so that America would be as proud of us as we are proud of her. I am very proud to have served my country and pleased that we can return with honor and dignity.”

Speaking of his time in Vietnam, RADM Shumaker stated:

“Paradoxically, I learned a lot about life from my experience as a prisoner of war in Vietnam. Those tough lessons learned within a jail cell have application to all those who will never have to undergo that particular trauma. At some point in life everybody will be hungry, cold, lonely, extorted, sick, humiliated, or fearful in varying degrees of intensity. It is the manner in which you react to these challenges that will distinguish you.

When adversity strikes, you’ve got to fall back with the punch and do your best to get up off the mat to come back for the next round. Realize that a person is not in total control of his destiny, but you need to know what your goals are, and you have to prepare yourself in advance to take advantage of opportunity when that door opens. Some important tools on the road to success include the ability and willingness to communicate, treating those around you with respect and courtesy no matter what their station in life might be, and conducting your life with the morality and behavior that will allow you to face yourself forever, in the end, you alone must be your own harshest critic.”

Rear Admiral Shumaker retired from the U.S. Navy on 01 February 1988. After retiring from the Navy, Shumaker became an assistant dean at George Washington University and later became the associate dean of the Center for Aerospace Sciences at the University of North Dakota. He is married to the former Lorraine Shaw of Montreal, Quebec, Canada. In April 2011 he was presented with the Distinguished Graduate Award from the U.S. Naval Academy. He has one son, Grant.

Since the war ended, nearly 10,000 reports relating to Americans missing, prisoner or unaccounted for in Southeast Asia have been received by the U.S. Government. Many authorities who have examined this largely classified information are convinced that hundreds of Americans are still held captive today. These reports are the source of serious distress to many returned American prisoners. They had a code that no one could honorably return unless all of the prisoners returned. Not only that code of honor, but the honor of our country is at stake as long as even one man remains unjustly held. It’s time we brought our men home.

Rear Admiral Joseph James Clark, United States Navy, Cherokee

One of Oklahoma’s distinguished, high ranking personnel in the forces of the United States in World War II, Rear Admiral Joseph James Clark, is a native Oklahoman of Cherokee descent. His outstanding service record compiled by the Navy Department is as follows:

One of Oklahoma’s distinguished, high ranking personnel in the forces of the United States in World War II, Rear Admiral Joseph James Clark, is a native Oklahoman of Cherokee descent. His outstanding service record compiled by the Navy Department is as follows:

Rear Admiral Clark was born in Pryor, Oklahoma, November 12, 1893, and prior to his appointment to the Naval Academy, he attended Willie Halsell College, Vinita, Oklahoma, and Oklahoma Agriculture and Mechanical College, Stillwater, Oklahoma. While at the Naval Academy he played lacrosse and soccer. He graduated with the Class of 1918 in June 1917, and during the World War served in the U.S.S. North Carolina which was engaged in convoying troops across the Atlantic. From 1919 to 1922 he served in destroyers in the Atlantic, in European waters and in the Mediterranean, and during the latter part of that duty served with the American Relief Administration in the Near East.

In 1922-1923 he had duty at the Naval Academy as instructor in the Department of Seamanship and Navigation, and qualified as a naval aviator at the Naval Air Station, Pensacola, Florida, on March 16, 1925. Later that year he joined the Aircraft Squadrons of the Battle Fleet and assisted Commander John Rodgers in preparing navigational data for the first West Coast-Hawaii flight in 1925, and received a letter of commendation for this service.

In 1926 he joined the U.S.S. Mississippi and served as her senior aviation officer and during the following year was aide on the staff of Commander, Battleship Division Three, and served as Division Aviation Officer.

From 1928 to 1931 Rear Admiral Clark was executive officer, Naval Air Station, Anacostia, D.C., and during the next two years was commanding officer of Fighter Squadron Two attached to the U.S.S. Lexington. He was the aeronautical member of the Board of Inspection and Survey, Navy Department, from 1933 to 1936 and during the next tour of sea duty July, 1936 to June, 1937, served as the Lexington‘s representative at Fleet Air Detachment. U.S. Naval Air Station, San Diego, California, and later as Air Officer of the Lexington. He was executive officer of the Fleet Air Base, Pearl Harbor, from July, 1937, to May, 1939. During the months of June and July he had additional duty with Patrol Wing Two, and, until the end of the year, was executive officer of the Naval Air Station at Pearl Harbor, afterwards serving as inspector of naval aircraft at the Curtis Aircraft Corporation, Buffalo, New York.

He was executive officer of the Naval Air Station, Jacksonville, Florida, from December 1940, until May 1941, when he reported for duty as executive officer of the old U.S.S. Yorktown, and in that carrier participated in the raid on the Marshall and Gilbert Islands. After detachment from the Yorktown he had duty in the Bureau of Aeronautics, Navy Department, Washington, D.C., from February 28 until June 20, 1942. He fitted out an auxiliary aircraft carrier, the U.S.S. Suwanee, and commanded her from her Commissioning.

For his service in this command during the assault on and occupation of French Morocco, he received the following Letter of Commendation by Admiral Royal E. Ingersoll, U.S.N., Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet:

“The Commander in Chief, United States Atlantic Fleet, notes with pleasure and gratification the report of your performance of duty as Commanding Officer of the U.S.S. Suwanee during the assault on and occupation of French Morocco from November 11, 1942. The Commander in Chief, United States Atlantic Fleet, commends you for the high efficiency, outstanding performance and skillful handling of the U.S.S. Suwanee and attached aircraft which contributed so notably to the unqualified success attained by the Air Group during this operation. Your meritorious performance of duty was in keeping with the highest traditions of the Naval Service.”

On February 15, 1943, he reported to the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, Newport News, Virginia in connection with fitting out the U.S.S. Yorktown and commanded her from commissioning until February 10, 1944. For his service in this command during the operations against Marcus, Wake, Mille, Jaluit, Makin, Kwajalein and Wotje, he has been awarded a Letter of Commendation by Vice Admiral John H. Towers, U.S.N., Commander, Air Force, Pacific Fleet, and a Silver Star Medal, with the following citations:

Letter of Commendation:

“For extraordinary performance and distinguished service in the line of his profession as commanding officer, U.S.S. Yorktown during the operations against Marcus Island on 31 August 1943 and against Wake Island on 5-6 October, 1943. On the first mentioned date, the air group of the Yorktown was launched at night and after a successful rendezvous was sent to Marcus Island and delivered the first attack before dawn. In this attack, the enemy was taken completely by surprise and all aircraft were destroyed on the ground. The subsequent attacks delivered by his air group contributed to the destruction of approximately eighty per cent of the installations on the island. On 5 October, 1943, his air group repeated a successful and effective attack on Wake Island before dawn. During this attack, eight enemy airplanes were destroyed in aerial combat and five were strafed on the ground. Eight additional airplanes were destroyed in the air by his air group in the following attack and eleven on the runways. Repeated bombing and strafing attacks were effectively delivered against all assigned objectives on that date. On 6 October, additional airplanes were strafed on the runways during a pre-dawn attack and severe damage wrought by dive bombing and strafing attacks on anti-aircraft and shore battery emplacements, fuel dumps, barracks, shops and warehouses. A total of 89 tons of bombs were dropped by his air group on assigned objectives. His outstanding leadership, his exceptional ability to organize and his courageous conduct throughout these engagements contributed immeasurably to the destruction of the enemy forces on these islands. His performance of duty was in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service.”

Silver Star Medal

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity as Commanding Officer of the U.S.S. Yorktown, during operations against enemy-held islands in the Central Pacific Area, from August 31 to December 5, 1943. Skillfully handling his ship during these widespread and extended operations, Rear Admiral (then Captain) Clark enabled aircraft based on his carrier to launch damaging attacks on enemy aircraft, shipping and shore installations on Marcus, Wake, Jaluit, Kwajalein and Wotje Islands. During the day and night of December 4, when the Yorktown was under severe enemy attack, almost continuously for one five-hour period at night, he maneuvered his vessel so expertly that all attacks were repelled without damage. By his devotion to duty throughout, he contributed materially to the success of our forces and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

The U.S.S. Yorktown was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for her heroism in action in the Pacific from August 31, 1943, to August 15, 1945. As her commanding officer during the first part of this period, Rear Admiral Clark received a facsimile of, and the ribbon for, this citation. The citation follows:

Presidential Unit Citation – USS Yorktown

“For extraordinary heroism in action against enemy Japanese forces in the air, at sea and on shore in the Pacific War Area from August 31, 1943, to August 15, 1945. Spearheading our concentrated carrier-warfare in forward areas, the U.S.S. Yorktown and her air groups struck crushing blows toward annihilating the enemy’s fighting strength; they provided air cover for our amphibious forces; they fiercely countered the enemy’s savage aerial attacks and destroyed his planes; and they inflicted terrific losses on the Japanese in Fleet and merchant marine units sunk or damaged. Daring and dependable in combat, the Yorktown with her gallant officers and men rendered loyal service in achieving the ultimate defeat of the Japanese Empire.”

On January 31, 1944, he was appointed Rear Admiral to rank from April 23, 1943. From February 1944 through June 1945 Rear Admiral Clark served as a Task Group Commander operating alternately with the First and Second Fast Carrier Task Groups of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, with the U.S.S. Hornet as his flagship. During this period he also was Commander of Carrier Division 13 (later redesignated Carrier Division 5). For his services during this period, Rear Admiral Clark was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal, a Gold Star in lieu of a Second Distinguished Service Medal, the Navy Cross, and the Legion of Merit. He also received a facsimile of and the ribbon for, the Presidential Unit Citation to the U.S.S. Hornet. The citations follow:

Distinguished Service Medal:

”For exceptionally meritorious service to the Government of the United States in a duty of great responsibility as Commander of a Task Group of Carriers and Screening Vessels in operations against enemy Japanese forces in the Pacific Area from April through June 1944. Participating in our amphibious invasion of Hollandia on April 21 to 24, Rear Admiral Clark’s well-coordinated and highly efficient units rendered invaluable assistance to our landing forces in establishing a beachhead and securing their positions and later, at the Japanese stronghold of Truk, helped to neutralize shore installations and planes both on the ground and in the air. By his keen foresight and resourcefulness, Rear Admiral Clark contributed in large measure to the overwhelming victories achieved by our forces against Japanese carrier-based aircraft, task units and convoys during the battle of the Marianas and attacks on the Bonin Islands. His indomitable fighting spirit and heroic leadership throughout this vital period were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

Navy Cross:

“For distinguishing himself by extraordinary heroism in operations against the enemy while serving as Commander of a Task Group in the vicinity of the Bonin Islands on 4 August, 1944. Upon receipt of information that an enemy convoy had been sighted proceeding in a northerly course enroute from the Bonins to the Empire, he immediately requested and received permission to organize an interception. He forthwith proceeded at high speed to lead his forces into Japanese home waters and intercepted the convoy, sinking five cargo vessels, four destroyer escorts and one large new type destroyer, while aircraft launched on his order searched within two hundred miles of the main islands of Japan shooting down two four engined search planes and one twin engined bomber as well as strafing and heavily damaging a destroyer and sinking three sampan type patrol vessels, and later in the day a light cruiser and an additional destroyer. By his professional skill, high personal courage, and superlative leadership, he inspired the units under his command to exceptional performance of duty in close proximity to strongly held home bases of the enemy. His conduct throughout was in keeping with the highest traditions of the Naval Service.”

Legion of Merit:

“For exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding service as Commander of a Task Group of the Fast Carrier Task Forces during the period from 24 March to 28 March 1945. On 24 March, he aggressively attacked a Japanese convoy of eight ships near the Ryuku Islands. By swift decisive action he directed planes of the Task group so that they were able to sink the entire convoy. On 28 March a sweep of Southern Ryuku was initiated by the Task Group Commander and resulted in the destruction of one Japanese destroyer and a destroyer escort, in addition to numerous Japanese aircraft. His quick thinking, careful planning and fighting spirit were responsible for a maximum of damage done to the enemy. His courage and devotion to duty were at all times inspiring and in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

Gold Star in lieu of Second Distinguished Service Medal

“For exceptionally meritorious service to the Government of the United States in a duty of great responsibility as Commander Task Group Fifty-Eight Point One during action against enemy Japanese forces in the Tokyo Area and the Ryukyus, and in supporting operations at Okinawa, from February 10 to May 29, 1945. Maintaining his Task Group in a high state of combat readiness, Rear Admiral Clark skillfully deployed the forces at his disposal for maximum effectiveness against the enemy. Directing operations with brilliant and forceful leadership, he was responsible for the swift interception of Japanese air groups flying in to attack our surface units and by his prompt and accurate decisions, effected extensive and costly destruction in enemy planes thereby minimizing the danger to our ships and personnel. As a result of his bold and aggressive tactics against hostile surface units on March 24 and 28, the planes of Task Group Fifty-Eight Point One launched a fierce aerial attack against a convoy of eight enemy ships near the Ryukyu Islands to sink the entire convoy during the first engagement and a hostile destroyer and destroyer escort in the second. Courageous and determined in combat, Rear Admiral Clark served as an inspiration to the officers and men of his command and his successful fulfillment of a vital mission contributed essentially to the ultimate defeat of the Japanese Empire.”

Presidential Unit Citation – USS Hornet

“For extraordinary heroism in action against enemy Japanese forces in the air, ashore and afloat in the Pacific War Area from March 29, 1944, to June 10, 1945. Operating continuously in the most forward areas, the USS Hornet and her air groups struck crushing blows toward annihilating Japanese fighting power; they provided air cover for our amphibious forces; they fiercely countered the enemy’s aerial attacks and destroyed his planes; and they inflicted terrific losses on the Japanese in Fleet and merchant marine units sunk or damaged. Daring and dependable in combat, the Hornet with her gallant officers and men rendered loyal service in achieving the ultimate defeat of the Japanese Empire.”

Returning to the United States in June 1945, Rear Admiral Clark resumed duty as Chief, Naval Air Intermediate Training Command, with headquarters at Corpus Christi, Texas, on June 27, 1945, and served in this capacity until September 1946. On September 7, 1946, he assumed duty as Assistant Chief of Naval Operations (Air), Navy Department, Washington, D.C.

In addition to the Navy Cross, the Distinguished Service Medal with Gold Star, the Legion of Merit, the Silver Star Medal, the Commendation Ribbon, and the Presidential Unit Citation Ribbon with two stars, Rear Admiral Clark has the Victory Medal, Escort Clasp (USS North Carolina), and is entitled to the American Defense Service Medal with Bronze “A” (for service in the old USS Yorktown which operated in actual or potential belligerent contact with the Axis Forces in the Atlantic Ocean prior to December 7, 1941); the European-African-Middle Eastern Area Campaign Medal with one bronze star; the Asiatic-Pacific Area Campaign Medal with twelve bronze stars; the Philippine Liberation Ribbon with one bronze star; and the World War II Victory Medal.

After retirement, Admiral Clark was a business executive in New York. His last position was Chairman of the Board of Hegeman Harris, Inc., a New York investment firm. Clark was an honorary chief by both the Sioux and Cherokee nations. He died 13 July 1971 at the Naval Hospital, St. Albans, New York, and is buried in Arlington National Cemeteryat Section 3, Site 2525-B.