Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 20

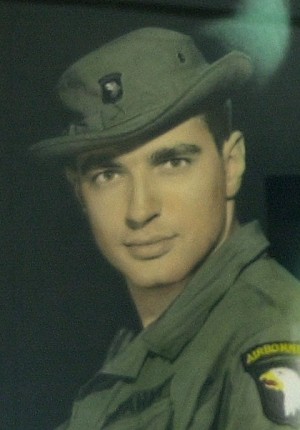

MCKNIGHT, GEORGE GRISBY

MCKNIGHT, GEORGE GRISBY

Branch/Rank: UNITED STATES AIR FORCE/O3

Unit: 602 ACS

Home City of Record: ALBANY OR

Date of Loss: 06-November-65

Country of Loss: NORTH VIETNAM

Aircraft/Vehicle/Ground: A1E

Missions: 50+MISSION

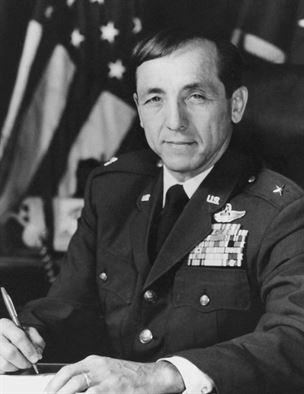

Colonel O-6, U.S. Air Force

U.S. Air Force Reserve 1955-1956

U.S. Air Force 1956-1986

Cold War 1955-1986

Vietnam War 1964-1973 (POW)

George McKnight was born in 1933 in Albany, Oregon. He was commissioned a 2d Lt in the U.S. Air Force through the Air Force ROTC program on July 15, 1955, and went on active duty beginning January 23, 1956. Lt McKnight completed pilot training and was awarded his pilot wings at Laredo AFB, Texas, in February 1957, and then completed F-100 Super Sabre Combat Crew Training in September 1957.

His first assignment was as an F-100 pilot with the 35th Fighter-Bomber Squadron at Itazuke AB, Japan, from October 1957 to June 1961 followed by service as an F-100 pilot with the 428th and then the 430th Tactical Fighter Squadron at Cannon AFB, New Mexico, from July 1961 to January 1965.

During this time, he deployed to Southeast Asia and flew combat missions from Takhli Royal Thai AFB, Thailand, from November to December 1964. Capt McKnight next completed A-1 Skyraider training at Eglin AFB, Florida, and then served as an A-1 pilot with the 602nd Fighter Squadron at Bien Hoa AB, South Vietnam, from July 1965 until he was forced to bail out over North Vietnam and was taken as a Prisoner of War on November 6, 1965. McKnight, a captain at the time, was taken as a POW in November 1965. He was an A-1 Skyraider pilot, assigned to the 602nd Fighter Squadron at Bien Hoa Air Base, South Vietnam. After spending 2,656 days in captivity, Col McKnight was released during Operation Homecoming on February 12, 1973. He was briefly hospitalized to recover from his injuries at Travis AFB, California, and then attended the Air War College at Maxwell AFB, Alabama, from August 1973 to July 1974.

Speaking about his POW experience, COL McKnight states:

“I was a POW for 7 years, 3 months, 2 days, 4 hours and 3 minutes,” he said of the confinement that lasted until the end of the war. He and 10 others, including U.S. Sen. John McCain, had a name for their prison and for themselves. “We called it Alcatraz Prison and ourselves the Alcatraz 11. We were all in solitary confinement.”

McKnight said he never saw his fellow American prisoners until they were released, with the exception of one escape attempt. Prisoners were kept in individual cells and communicated with one another by tapping on the walls — a code they learned in case they were captured.

“It was exactly like text messaging,” he said with a laugh. “So we invented it. We want our money back.”

When he returned to the Air Force War College in Montgomery, Ala., he met a woman in the Nurse Corps. He and Suzanne married, and 34 years later are “living happily ever after.”

To McKnight, Veterans Day is a time to especially honor the country’s young service men and women.

“It’s amazing they can get those men and women without the threat of the draft,” he said, his voice catching with emotion. “Those guys today are volunteers. So they are very special soldiers.”

His next assignment was to flight retraining and F-4 Phantom II Combat Crew Training before serving as Special Assistant to the Deputy Chief of Operations for the 463rd Tactical Fighter Squadron at RAF Lakenheath, England, from March 1975 to April 1976.

COL McKnight then served as Deputy Commander for Operations of the 32nd Tactical Fighter Squadron at Camp New Amsterdam in the Netherlands from May 1976 to March 1978, followed by studies at the Defense Language Institute and then service as Defense Air Attaché to the Democratic Republic of the Congo from October 1978 to May 1982. His final assignment was as Commander in Chief of the U.S. Air Force/Canadian Forces Officer Exchange Program in Ottawa City, Canada, from November 1982 until his retirement from the Air Force on March 1, 1986.

His Air Force Cross Citation reads:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Section 8742, Title 10, United States Code, awards the Air Force Cross to Lieutenant Colonel George G. McKnight for extraordinary heroism in military operations against an opposing armed force while a Prisoner of War in North Vietnam on 12 October 1967. On that date, he executed an escape from a solitary confinement cell by removing the door bolt brackets from his door. Colonel McKnight knew the outcome of his escape attempt could be severe reprisal or loss of his life. He succeeded in making it through a section of housing, then to the Red River and swam down river all night. The next morning he was recaptured, severely beaten, and put into solitary confinement for two and a half years. Through his extraordinary heroism and aggressiveness in the face of the enemy, Colonel McKnight reflected the highest credit upon himself and the United States Air Force.

CAN MUSLIMS BE GOOD AMERICANS?

This question was forwarded to a friend who worked in Saudi Arabia for 20 years. The following is his reply:

This question was forwarded to a friend who worked in Saudi Arabia for 20 years. The following is his reply:

Theologically – No. Because his allegiance is to Allah, The moon god of Arabia.

Religiously – No. Because no other religion is accepted by His Allah except Islam. (Quran,2:256)(Koran)

Scripturally – No. Because his allegiance is to the five Pillars of Islam and the Quran.

Geographically – No. Because his allegiance is to Mecca, to which he turns in prayer five times a day.

Socially – No. Because his allegiance to Islam forbids him to make friends with Christians or Jews.

Politically – No. Because he must submit to the mullahs (spiritual leaders), who teach annihilation of Israel and destruction of America, the great Satan.

Domestically – No. Because he is instructed to marry four Women and beat and scourge his wife when she disobeys him. (Quran 4:34)

Intellectually – No. Because he cannot accept the American Constitution since it is based on Biblical principles and he believes the Bible to be corrupt.

Philosophically – No. Because Islam, Muhammad, and the Quran do not allow freedom of religion and expression. Democracy and Islam cannot co-exist. Every Muslim government is either dictatorial or autocratic.

Spiritually – No. Because when we declare ‘one nation under God,’ The Christian’s God is loving and kind, while Allah is NEVER referred to as Heavenly father, nor is he ever called love in the Quran’s 99 excellent names.

Therefore, after much study and deliberation… Perhaps we should be very suspicious of ALL MUSLIMS in this country. They obviously cannot be both ‘good’ Muslims and ‘good’ Americans. Call it what you wish it’s still the truth. You had better believe it. The more who understand this, the better it will be for our country and our future.

The religious war is bigger than we know or understand!

Footnote: The Muslims have said they will destroy us from within. SO FREEDOM IS NOT FREE.

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 17

Name: Samuel Robert Johnson

Name: Samuel Robert Johnson

Rank/Branch: O4/United States Air Force

Unit: 433rd TFS

Date of Birth: 11 October 1930

Home City of Record: Dallas TX

Date of Loss: 16 April 1966

Country of Loss: North Vietnam

Status (in 1973): Returnee

Aircraft/Vehicle/Ground: F4C

Missions: 25

NOTE: Flew 62 missions in Korea in F-86’s

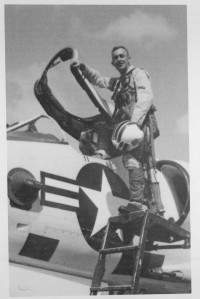

Samuel Robert “Sam” Johnson (born October 11, 1930) is a retired career U.S. Air Force officer and fighter pilot and an American politician. He currently is a Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives from the 3rd District of Texas. The district includes much of Collin County, as well as Plano, where he lives.

Johnson grew up in Dallas and graduated from Woodrow Wilson High School. Johnson graduated from Southern Methodist University in his hometown in 1951, with a degree in business administration. While at SMU, Johnson joined the Delta Chi social fraternity as well as the Alpha Kappa Psi business fraternity. He served a 29-year career in the United States Air Force, where he served as director of the Air Force Fighter Weapons School and flew the F-100 Super Sabre with the Air Force Thunderbirds precision flying demonstration team. He commanded the 31st Tactical Fighter Wing at Homestead AFB, Florida and an air division at Holloman AFB, New Mexico, retiring as a Colonel.

He is a veteran of both the Korean and Vietnam Wars as a fighter pilot. During the Korean War, he flew 62 combat missions in the F-86 Sabre. During the Vietnam War, Johnson flew the F-4 Phantom II.

In 1966, while flying his 25th combat mission in Vietnam, he was shot down over North Vietnam. He was a prisoner of war for seven years, including 42 months in solitary confinement. During this period, he was repeatedly tortured.

Johnson was part of a group of 12 prisoners known as the Alcatraz Gang, a group of prisoners separated from other captives for their resistance to their captors. They were held in “Alcatraz”, a special facility about one mile away from the Hỏa Lò Prison, notably nicknamed the “Hanoi Hilton”. Johnson, like the others, was kept in solitary confinement, locked nightly in irons in a 3-by-9-foot cell with the light on around the clock. Johnson recounted the details of his POW experience in his autobiography, Captive Warriors(available through amazon).

Mr. Johnson states “The nearly seven years that I spent in Hanoi but most especially the more than two years in a camp called Alcatraz engendered a close-knit bond between me and some great Americans. I count these men as true friends and their courage and ideals have brought home vividly to me what America is all about. I can only emphasize that the freedoms that most Americans take for granted are in fact, real and must be preserved. I have returned to a great nation and our sacrifices have been well worth the effort. I pledge to continue to serve and fight to protect the freedoms and ideals that the United States stands for” and he has done so.”

A decorated war hero, Johnson was awarded two Silver Stars, two Legions of Merit, the Distinguished Flying Cross, one Bronze Star with Combat “V” for Valor, two Purple Hearts, four Air Medals, and three Air Force Outstanding Unit Awards. He was also retroactively awarded the Prisoner of War Medal following its establishment in 1985. He walks with a noticeable limp, due to an old war injury.

After his military career, he established a homebuilding business in Plano. He was elected to the Texas House of Representatives in 1984 and was re-elected four times. In 1990, Johnson was inducted into the Woodrow Wilson High School Hall of Fame. In October 2009, the Congressional Medal of Honor Society awarded Johnson the National Patriot Award, the Society’s highest civilian award given to Americans who exemplify patriotism and strive to better the nation.

On May 8, 1991, he was elected to the House in a special election brought about by eight-year incumbent Steve Bartlett’s resignation to become mayor of Dallas. Johnson defeated fellow conservative Republican Thomas Pauken, also of Dallas, 24,004 (52.6 percent) to 21,647 (47.4 percent). Johnson thereafter won a full term in 1992 and has been reelected nine times. The 3rd has been in Republican hands since 1968. The Democrats did not even field a candidate in 1992, 1994, 1998, or 2004.

2004: Johnson ran unopposed by the Democratic Party in his district in the 2004 election. Paul Jenkins, an independent, and James Vessels, a member of the Libertarian Party ran against Johnson. Johnson won overwhelmingly in a highly Republican district. Johnson garnered 86% of the vote (178,099), while Jenkins earned 8% (16,850) and Vessels 6% (13,204).

2006: Johnson ran for re-election in 2006, defeating his opponent Robert Edward Johnson in the Republican primary, 85 to 15 percent. In the general election, Johnson faced Democrat Dan Dodd and Libertarian Christopher J. Claytor. Both Dodd and Claytor are West Point graduates. Dodd served two tours of duty in Vietnam and Claytor served in Operation Southern Watch in Kuwait in 1992. It was only the fourth time that Johnson had faced Democratic opposition. Johnson retained his seat, taking 62.5% of the vote, while Democrat Dodd received 34.9% and Libertarian Claytor received 2.6%. However, this was far less than in years past, when Johnson won by margins of 80 percent or more.

2008: Johnson retained his seat in the House of Representatives by defeating the Democrat Tom Daley and Libertarian nominee Christopher J. Claytor in the 2008 general election. He won with 60 percent of the vote, an unusually low total for such a heavily Republican district.

2010: Johnson won re-election with 66.3% of the vote against Democrat John Lingenfelder (31.3%) and Libertarian Christopher Claytor (2.4%).

2014: Johnson handily won re-nomination to his thirteenth term, twelfth full term, in the U.S. House in the Republican primary held on March 4, 2014. He polled 30,943 votes (80.5 percent); two challengers, Josh Loveless and Harry Pierce, held the remaining combined 19.5 percent of the votes cast.

In the House, Johnson is an ardent conservative. By some views, Johnson had the most conservative record in the House for three consecutive years, opposing pork barrel projects of all kinds, voting for more IRAs and against extending unemployment benefits. The conservative watchdog group Citizens Against Government Waste has consistently rated him as being friendly to taxpayers. Johnson is a signer of Americans for Tax Reform’s Taxpayer Protection Pledge. Johnson is a member of the conservative Republican Study Committee, and joined Dan Burton, Ernest Istook and John Doolittle in re-founding it in 1994 after Newt Gingrich pulled its funding. He alternated as chairman with the other three co-founders from 1994 to 1999, and served as sole chairman from 2000 to 2001.

On the Ways and Means Committee, he was an early advocate and, then, sponsor of the successful repeal in 2000 of the earnings limit for Social Security recipients. He proposed the Good Samaritan Tax Act to permit corporations to take a tax deduction for charitable giving of food. He chairs the Subcommittee on Employer-Employee Relations, where he has encouraged small business owners to expand their pension and benefits for employees. Johnson is a skeptic of calls for increased government regulation related to global warming whenever such government interference would, in his mind, restrict personal liberties or damage economic growth and American competitiveness in the market place. He also opposes calls for government intervention in the name of energy reform if such reform would hamper the market and or place undue burdens on individuals seeking to earn decent wages. He has expressed his belief that the Earth has untapped sources of fuel, and has called for allowing additional drilling for oil in Alaska. Johnson is one of two Vietnam-era POWs still serving in Congress.

Johnson is married to the former Shirley L. Melton, of Dallas. They are parents of three children and ten grandchildren.

2nd Amendment

Constitution Lesson #2 – I feel that there is no room for interpretation on this. The reason this amendment was put in the Constitution was so that the people would be equally armed and capable of throwing off the shackles of a tyrannical government if it ever came to that again. For those that argue that we do not need firearms available, try using an M-16 A2 against a Tank. We are already out gunned and the underdog. If you have any opinion that there should be more gun control and bans than there already are, then you probably do not belong in America. It is very cut and dry. Read, study, discuss, and ask questions.

Constitution Lesson #2 – I feel that there is no room for interpretation on this. The reason this amendment was put in the Constitution was so that the people would be equally armed and capable of throwing off the shackles of a tyrannical government if it ever came to that again. For those that argue that we do not need firearms available, try using an M-16 A2 against a Tank. We are already out gunned and the underdog. If you have any opinion that there should be more gun control and bans than there already are, then you probably do not belong in America. It is very cut and dry. Read, study, discuss, and ask questions.

SECOND AMENDMENT OF THE CONSTITUTION

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

Shall not be infringed. So it’s stops there. It’s unconstitutional to even have to get a firearm ID card, permits, and registration for the firearm

Shall not be infringed! Enough said!

So with ‘them’ wanting to twist in laws of regulations on our purchases, do we stick solely to gun shows and private sales for guns and ammo? I mean, that would be the best option right?

As of right now, that does seem like the best option for many. Again, it is the same as the First Amendment; it really depends on what state you live in anymore. The more the government knows about you, the more they can use against you. No sense in giving them more intelligence that isn’t necessary. I could understand why someone would not want “them” knowing you purchased a firearm.

I still can’t get over the fact that when this was written other than a few cannon some may have had the use of that the actual arms were exactly the same yet some ill informed people think that we should only have muskets. This document is not frozen in time it evolves with the world. If the first amendment covers current communication why can’t they see the second covers current arms?

We have guns registered by state. The others were private sale. But now I even wonder about the ammo I just bought last week at a store. I mean, what else have ‘they’ been monitoring besides our emails and phone calls? Start making your own ammo. Reloading is a useful skill to take up.

Some of the liberals have their heads buried so far up their butt that they actually think the 2nd amendment was created for hunting and recreation.

“Shall not be infringed” says it all. But it also talks about a well regulated militia. And I think that’s a very important part. Together we are stronger.

The discipline and regulation of said militia is important so that you do not have a bunch of disorganized idiots running around trying to play Rambo.

“A well regulated militia…” The army national guard? Or private militias? Which would that apply to?

Private. Thought so. I thought that was private such as the minutemen.

Private; meaning the individual citizen, meaning all of us who individually elect to do so.

Wouldn’t it stand for both as a militia consists of 2 parts, organized (state guards) and unorganized (private militias consisting of every able bodied citizen)?

Having a firearm is not about fighting police or government agents. Having a firearm represents that you are prepared for the absolute worst, heaven forbid. Nobody thinks they are going to stop tanks with an AR. The original purposes of the rifle were for competition shooting, and varmint hunting. I think blaming responsible gun owners is absolute nonsense. I don’t know a single gun owner who would willingly supply arms to a criminal or felon, for any amount. The very nature of half of the gun control arguments derive from fear and ignorance of a craft, hobby and a divine right. Not divine from God, but from Nature. You have the right to defend yourself, and we all know there are awful excuses for human beings on this planet. Every time I turn the news on, or log into Facebook, a girl got raped, a couple got murdered, and we’re on the brink of another war. Enough already. Stop demonizing good, law abiding people. We get it. Stop hurting the working class, and stop demonizing innocent people.

It encourages all citizens to be soldiers so to speak. Well armed to defend freedom, more on a domestic level.

It is so cut and dry that the only point that was possibly discussable was the private militia, and that was short lived. It’s simple and profound.

As is the whole Constitution. It is on two pages for the Constitution and one page for the Declaration of Independence so that it would be short, to the point, and easily interpreted. Very different from today’s legislative/Congressional bills.

A private militia can be commanded by an ex or retired Officer of the US Armed Forces.

Go and by a fresh replica today of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights today. Look at them, and be amazed by the fact they were only 2 pieces of parchment!

Simple yet priceless words.

Militias are perfectly legal. They have to be known to the government, but they are legal. There are many, and at least one in every state.

That is if you want to do it the law way, which is a good idea, or they can shut you down in a hurry, technically.

Many people I know of are part of the state militia but also do “activities” in smaller groups. Squad size, if you will.

The bad thing is that the left wing media has painted a bad picture for militias even though they have not been in a terrorist attack.

Here’s the thing with the militia. You run around calling yourself a MILITIA, and people automatically think NUT JOB. We don’t need this. Instead of running around like idiots, in surplus army gear, just practice shooting with your buddies at a range. The left wing media make militias look like neo Nazi and crazy hillbillies.

Shall not be infringed . . . there is nothing more to be said . . . no one has the authority to take away something God has given.

This is the sad part . . . how can someone paint something as “terroristic” that is perfectly legal according to the United States Constitution?

People pin Patriots in a bad light to convince the weak that “Patriots” are bad and the government is justified for taking our rights away.

The only good thing about the Left is that they make themselves look like total idiots multiple times on a daily basis. What people forget is that liberal sentiment resides on the coasts, but inland, central, northern, and southern parts of the United States are a different world. This is still a 50/50 fight at the least. Sure, liberals control the media, but we are fixing that. Gun owners, both Red and Blue States, are telling the current regime no way their gun control agenda will work and it is falling apart.

“Shall not be fringed upon”. Enough said!

The Second Amendment says ‘the right of the people’, it does not say it is a privilege; and that RIGHT SHALL NOT be infringed. We know that felons are not allowed firearms. It does not pertain to misdemeanercrime too. My question is this. Are the rights of those felons regardless if it’s a violent crime or not, are their rights being infringed upon? I’ve heard said that gun ownership is a privilege not a right. That rights can’t be taken but privilege can. I do know of rights that are trampled on every day. I wonder also if background checks then infringe. The point of a background check would be for them to prepare to infringe.

Insulting Militia is not going to get us anywhere when many people on here are in and support militias. It is a right protected by the Constitution to form militias. I agree that it needs to be organized, but as was stated by the boss earlier, in fighting isn’t going to be tolerated.

But you don’t just have to be a felon domestic dispute will get them taken as well regardless. Form a hunting club, or a marksmanship team. Network with police officers, and sheriff’s deputies whenever possible. Get in good with your neighbors. Practice your sport. Get proficient. This should be your new craft or hobby on the same level of “Bowling, Softball, Volleyball, Flag Football,” or whatever you used to occupy your time with.

When the law was written, most felons would have seen the gallows. No reason to restrict their firearm ownership. Take their lives. They don’t sit on death row clogging up the legal system with endless appeals. Background checks, waiting periods and limits on types and modifications are ALL ways of infringing on our God-given right to protect ourselves from a government that’s gotten too big for its breeches. I’m a firm believer that if you can afford to buy a weapon that’s very much a military weapon, like an M134 Dillon Minigun or an M1 Abrams tank and it’s various ammunition and armament, you should be allowed to.

Host shooting competitions. For the love of god, Develop Rifle Competency!

The first ‘assault rife’- the lever-action repeating rifle, was immediately available to any civilian that had the money to purchase one . . . of course when the second amendment was penned private citizens owned cannon, mortars and naval warships, there was no discussion at that time about limiting possession of ‘arms’ based on their type . . . if you had the money you could own whatever you wanted we’ve gotten very far away from what was intended when the amendment was written . . . for the most part because the elected elite are scarred to death that WE THE PEOPLE might actually remember why that right is enumerated and might actually exercise it in for its intended purpose . . .

THE RIGHT OF THE PEOPLE . . . Shall NOT BE INFRINGED . . . In Simple English . . . Any Questions?

Whoever controls the money and the weapons, has the power . . . That’s what they want . . . And the social media and news media promote it . . . They hope we are too busy playing and not watching . . . .

This amendment is so simple, it raises too many questions. No wonder it’s so difficult for a liberal to understand.

It is well put. It is difficult to have a discussion with people that an automatic firearm should be legal.

“Shall not be infringed ” doesn’t get any more clear than that!!!

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 13

Name: Ronald Edward Storz

Name: Ronald Edward Storz

Branch/Rank: United States Air Force/O3

Date of Birth: 21 October 1933

Home City of Record: SOUTH OZONE PARK NY

Date of Loss: 28 April 1965

Country of Loss: North Vietnam

Status (in 1973): Prisoner of War/Died in Captivity

Category: 1

Aircraft/Vehicle/Ground: O1A

The following is QUOTED directly from THE PASSING OF THE NIGHT, by Brigadier Gen Robinson Risner, Copyright 1973, Ballantine Books. Pages 63 – 71.

“One day they replaced Shumaker with Air Force Captain Ron Storz. I tapped on the wall to him, got his name, and so forth. He said that up until this move, he had been living with Captain Scotty Morgan. “I leaned on the door and broke the lock. Now I am over here alone being punished.” Ron told me he had been shot down in an L 1 9, one of those little planes called grasshoppers. Since he, as a forward air controller, normally worked with Vietnamese ground forces, he would carry a Vietnamese officer in the back seat. His mission was to circle and spot enemy positions or helps the artillery batteries adjust for accuracy. “One afternoon I decided to go up and buzz around by myself. I was just looking the area over, and I circled real close to the Ben Hi River. I knew that was the seventeenth parallel, but I didn’t mean to get over the river. When I did, a Vietnamese gun got me, and tries as I might, I could not keep from crashing on the north side. I thought they were going to kill me when I got out of the airplane. They made me get down on my knees. One of the officers took my gun, cocked it and put it against my head. I figured I was a goner.” He had been in prison for some time and really wanted to talk. I could hear him moving around in the other cell. He hollered out the back vent as Bob before him had done, but I could never understand him. We tapped on the wall, but it was too slow and unsatisfactory.

There were a lot of things we wanted to tell each other. Finally he asked, by tapping, “Have you tried boring a hole through the wall yet?” I told him I had tried several places but could not get through. “Each time I try, I hit a brick after I’ve gone in maybe eight to twelve inches.” I had several partial holes; in fact, the wall looked like a piece of Swiss cheese. “Well, I’ll try, too.” Pretty soon I heard some scraping and grinding. By that afternoon he was through. His hands were blistered, but he had made it. That gave me some incentive to try to go through the other wall. I really went to work, and I punched through there, too. We passed our tools through and let them work in the next room. In a few days, every room was connected up and down the hall.

Once we got the holes bored through, Ron said, “I’m really down in the mouth.” I asked what the matter was. “Well, just the fact that I have nothing. They have taken everything away from me. They took my shoes, my flying suit, and everything I possessed. They even took my glasses. I don’t have a single thing. They took everything.” Ron had indicated to me that he planned to become a minister when he got back to America. Consequently we talked about religion quite a bit, as all of us did. When he said he was depressed because they had taken everything, I told him, “Ron, I don’t think we really have lost everything.” “What do you mean?” “According to the Bible, we are sons of God. Everything out there in the courtyard, all the buildings and the whole shooting match belong to God. Since we are children of God, you might say that all belongs to us, too.” There was a long pause. “Let me think about it, and I’ll call you back.” After a while he called back, “I really feel a lot better. In fact, every time I get to thinking about it, I have to laugh.” “What do you mean?” “I am just loaning it to them.” I will never forget the day he called me and told me, “They’re trying to make me come to attention for the guards and I will not do it. What do you think I ought to do?” “What do they do?” “They cut my legs with a bayonet, trying to make me put my feet together. I am just not going to do it.” I knew he meant it. He was an extremely strong man. I thought about it for a while, then I called back, “Ron, I’m afraid we don’t have the power to combat them by physical force. I believe I would reconsider. Then, if we decide differently, we all should resist simultaneously. With only you resisting while everybody else is doing it means you are bound to lose.” He said, “Okay.” I knew, though, that if I had said, “Ron, hang tough! Refuse to snap to,” he would have done it without batting an eye. He was just that kind of man and he proved it a short time later.

It happened after we had begun to set up a covert communications system throughout the Zoo. By means of the holes in the walls, special hiding places in the latrine and other ways, we could pass a message through the entire camp within two days. I had put out directives establishing committees and worked out a staff. Certain people had been assigned specific jobs. One man was heading up our communications section. We had a committee working on escape. And we kept a current list of all the POWs and their shoot-down date. I then decided to put out a bulletin. It was not too large, but it contained directives, policies and suggestions. Since Ron was next door to me, I dictated it to him, and he wrote it down. Despite the Vietnamese’s denying us our dues as POWs, I still felt that we could outsmart them by using tactics such as these. We had only been at the Zoo around four weeks; given time, I reasoned, we could begin to effect some changes. I could not have been more wrong. One day during this period, a guard came in and made me stand at attention with my back to the wall. In a few minutes the Dog came in with another Vietnamese in a white shirt. The Dog did not say who the civilian was, but he paid him a lot of deference. Using the Dog as an interpreter, the civilian made a statement: “I understand you are also a Korean hero.” I was still standing braced against the Wall. “That is military information and I cannot answer. I can give you only my name, rank, serial number and date of birth.” When he heard the translation, the cords in his neck swelled up and he tamed red in the face. “We know how to handle your kind. We are preparing for you now.” He turned and stomped out. The Dog came back in a little while. He was either so scared or mad that he was still trembling “You have made the gravest mistake in your life. You will really suffer for this.”

With that threat he left. A few days later a guard caught the men two cells above me talking through the hole in the wall to Ron. He also found some written material. Then he went into Ron’s room and caught him by surprise. He took two pieces of written work Ron had prepared; one was a list of all the POW names, the other was one of the bulletins I had put out. To make matters worse, Ron had put my real name on the newssheet instead of my code name, “Cochise.” While still in the cell, one of the guards began reading the two sheets. Ron reached over, snatched one and ate it while holding them off with one hand. Unfortunately he had grabbed the wrong one. He ate the list of names which was not too important, but they kept the list of directives. They also found the hole in the wall. This so excited them that they stepped out in the hall yelling for reinforcements. While they were out, Ron ran over to my wall and beat out an emergency signal to come to our hole in the wall. They searched and found everything. I ate the list of names, but they got the policies. Get rid of anything you don’t want them to find.” I told him to deny everything, and I would do the same.

He just had time enough to stuff the plug back in the hole when they came and took him away. I passed the warning down to the other two rooms and they began to clean house. As fast as possible I began to try and dispose of anything incriminating. The steel rods that we had been using to bore the holes in the walls I put under the floor through the grate. I destroyed lots of paperwork, but the fat was in the fire. A big shakedown was on. One thing I had not destroyed was a sheet of toilet paper that had the Morse code on it. I didn’t think it was any big deal or I would have gotten rid of it. This was one of the pieces of evidence they would use to accuse me of running a communications system. The irony of it was that I actually was relearning the Morse code with the knowledge of my turnkey. He had even written his name on it for me.

They put Ron in another room for three days and nights without anything at all – no food, water, bedding, blankets or mosquito net. They just shoved him in and left him there. He not only got cold, but the mosquitoes chewed on him all night. They took me before the camp commander for interrogation. He had the piece of paper Ron had not been able to destroy and started reading the fourteen items it listed, such as: gather all string, nails and wire; save whatever soap or medicine you get; familiarize yourself with any possible escape routes; become acquainted with the guards, and in general follow the policy that “you can catch more flies with sugar than, with vinegar.” I denied the paper was mine. “Storz has already admitted everything and said you were responsible.” I knew that was a lie.

They would have had to kill Ron before he did that. He might admit to his having done it, but he would never say that somebody else had. They, of course, told him the same thing and said that I had admitted everything, and all he had to do was confirm it. After making the usual number of threats, they took me back to a different room at the end of the building. They left me a pencil and paper and told me to write out a confession that I had violated prison rules. “If you do not, you will be severely punished.” The first thing I knew, I heard a tap. It was Ron Storz in the next room. We exchanged what had happened in interrogation. I said, “Remember, I’ll never confess to anything.” “Roger, I won’t either.” He then tapped, “God bless you.” I sent back a GBU. I later heard that Ron was put in Alcatraz, a harsh punishment camp. Though he was an extremely strong man, the torture began to get through to him. The North Vietnamese hated him so that even when they moved out all the other POWs, they left Ron there alone. I later saw one of the postage stamps put out by the North Vietnamese. It was typical North Vietnamese propaganda. On it is a picture of an American POW. He is big and tall. Behind him is a teen-age girl, very small, holding a rifle on him. The American was Ron Storz. When making their report on the POWs in 1973, the North Vietnamese said that Ron Storz “died in captivity.” Ron Storz died as he lived – a brave American fighting man who considered his principles more valuable than his life.”

Ron Storz was beaten unconscious and died on 23 April 1970. His remains were recovered and returned on March 6, 1974.

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 12

THOMAS MICHAEL HANRATTY

Name: Thomas Michael Hanratty

Rank/Branch: Lance Corporal/US Marine Corps

Unit: HMM 265, Marine Air Group 16

Date of Birth: 19 June 1946 (Pueblo, CO)

Home of Record: Beulah, CO

Date of Loss: 11 June 1967

Country of Loss: South Vietnam

Status in 1973: Killed/Body Not Recovered

Category: 2

Aircraft/Vehicle/Ground: CH46A “Sea Knight”

Other Personnel In Incident: Curtis R. Bohlscheid; Charles D. Chomel; Dennis Christie; John J. Foley; Jose J. Gonzales; Michael W. Havranek; James W. Kooi; Jim E. Moshier; John S. Oldham; James E. Widener (missing)

REMARKS: A/C CRASH-EXPLODED-NO SURVS OBS-J

The Boeing-Vertol CH46 Sea Knight arrived in Southeast Asia on 8 March 1966 and served the Marine Corps throughout the rest of the war. With a crew of three or four depending on mission requirements, the tandem-rotor transport helicopter could carry 24 fully equipped troops or 4600 pounds of cargo and was instrumental in moving Marines throughout South Vietnam, then supplying them accordingly.

Because the war in Vietnam lacked a defined front line, the enemy strategy made Long Range Reconnaissance Patrols (LRRP) a needed tool to gather intelligence about communist activities throughout Southeast Asia. The ground commanders who fought the day to day war readily recognized the need for special reconnaissance units at the onset of the fighting. During 1965 provisional LRRP units were formed with all assets they could spare.

On 11 June 1967, Capt. Curtis R. “Dick” Bohlscheid, pilot; Major John S. Oldham, co-pilot; LCpl. Jose J. Gonzales, crewchief; and LCpl. Thomas M. Hanratty, door gunner; comprised the crew of the lead CH46A helicopter (aircraft #150270) on a troop insertion mission. A total of four aircraft were involved in the mission, two CH46 troop transports and two UH1E helicopter gunships that were providing air cover for the transports. In addition to being the aircraft commander of the lead Sea Knight, Capt. Bohlscheid was also the mission commander.

Cpl. Jim E. Moshier, LCpl. Dennis Christie, LCpl. James W. Kooi, LCpl. John J. Foley, LCpl. Michael W. Havranek, PFC Charles Chomel and PFC James E. Widener comprised half of Marine Reconnaissance Team (RT) Somersail One, being inserted into a designated landing zone (LZ). RT Somersail One was on an intelligence gathering mission. Early that morning Capt. Bohlscheid briefed the aircrews on the mission flight plan, while the reconnaissance team waited outside.

The flight of four aircraft departed Dong Ha and proceeded to the southern boundary of the demilitarized zone (DMZ) to an area located in the jungle covered mountains approximately 4 kilometers north of Hill 208, which was identified as the NVA’s 324B Division Command Post during Operation Hastings. It was also located 900 meters west of Hill 174, another well known NVA position.

Capt. Bohlscheid first attempted to insert the RT Somersail One west of a landmark known as “The China Wall.” The flight pulled away from the briefed LZ when the gunships, which were clearing the LZ by making low strafing passes over the landing zone to set off any booby traps that might have been placed there as well as to locate any enemy positions, began taking enemy ground fire.

The flight returned to Dong Ha to refuel, rearm and plan a second insertion mission attempt. The second attempt was made directly at the base of The China Wall, but once again it was driven off. For the second time the helicopters returned to Dong Ha to rearm, refuel and evaluate their options.

Because of the heavy NVA pressure in the area and the need to gather current intelligence about their activities, headquarters ordered RT Somersail One be inserted at all cost. The four aircraft returned to the DMZ for the third time in a matter of hours. This time the location chosen was approximately 5 miles northwest of Firebase Vandergrift, 9 miles south of the demilitarized zone (DMZ) and 11½ miles northwest of Dong Ha, Quang Tri Province, South Vietnam.

Before the Sea Knights landed, both gunships again went to work clearing the proposed LZ. This time no booby traps were sprung and no enemy fire was received. As the Hueys strafed the area, the members of RT Somersail One prepared to initiate their mission once the insertion was completed. Hank Trimble was the pilot of one of the gunship escorts. After clearing the LZ, he stationed his aircraft to the left of Dick Bohlscheid’s, then radioed him to proceed to the LZ.

At 1115 hours, the Sea Knight made its approach. At an estimated altitude of 400-600 feet above the ground, the helicopter transitioned from travel to landing speed. As the lead troop transport did so, other flight members observed it climb erratically in a manner similar to an aircraft commencing a loop. At the same time Capt. Bohlscheid radioed that they had been hit by machinegun fire.

As those aboard the other helicopters watched in horror, portions of the rear rotor blades were seen to separate from the Sea Knight. In almost slow motion, the helicopter’s nose rose, then rose more sharply and continued to climb toward the sky until it was nearly vertical to the ground. It rolled to an inverted position then appeared to perform a “split S” maneuver before it burst into flames and continued out of control. Hank Trimble reported that Dick Bohlscheid keyed his mic at the time he was inverted and started to say something, but what came out was a strangled cry, “Mama.” The Sea Knight crashed into a steep ravine on the north side of a stream that ran through it.

Ground units subsequently entered the area to search for survivors or recover the remains of the dead if possible. Due to a well-entrenched and equally well camouflaged enemy bunker complex surrounding the entire LZ and crash site, the ground units could only inspect the site through binoculars from a distance of approximately 500 meters. During the brief time available to them, they observed no survivors in or around the aircraft wreckage. At the time the ground mission was terminated, all eleven Marines were listed Killed In Action, Body Not Recovered.

If the crew and passengers aboard the Sea Knight died in their loss incident, each man has a right to have his remains returned to his family, friends and country. However, if any of them were thrown free and managed to survive, the large number of enemy troops actively operating in this region most certainly would have captured them. Either way there is no doubt the Vietnamese could account for them any time they had the desire to do so.

For other Americans who remain unaccounted for their fate could be quite different. Since the end of the Vietnam War well over 21,000 reports of American prisoners, missing and otherwise unaccounted for have been received by our government. Many of these reports document LIVE America Prisoners of War remaining captive throughout Southeast Asia.

Military men in Vietnam were called upon to fly and fight in many dangerous circumstances, and they were prepared to be wounded, killed or captured. It probably never occurred to them that they could be abandoned by the country they so proudly served.

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 14

Born: 22 February 1948 Kufstein, Austria

Died: 10 May 1970 (aged 22) Se San, Cambodia

Place of burial: North Sewickley Township, Beaver County, Pennsylvania

Allegiance: United States of America

Service/branch: United States Army

Years of service: 1969–1970

Rank: Sergeant (posthumous)

Unit: 506th Infantry Regiment

Battles/wars: Vietnam War: Cambodian Campaign

Awards: Medal of Honor; Bronze Star; Purple Heart; Air Medal

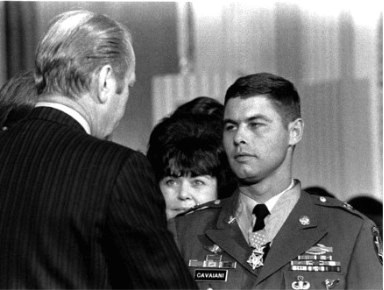

Leslie Halasz Sabo, Jr. (Hungarian: ifj. Halász Szabó László) (22 February 1948 – 10 May 1970) was a soldier in the United States Army during the Vietnam War. He received the highest military decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his actions during the Cambodian Campaign in 1970.

Born in Kufstein, Austria, Sabo’s family immigrated to the United States when he was young and moved to Ellwood City, Pennsylvania. Sabo dropped out of college and was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1969, becoming a member of the 506th Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. On 10 May 1970 Sabo’s unit was on an interdiction mission near Se San, Cambodia when they were ambushed from all sides by the Vietnam People’s Army. Sabo repeatedly exposed himself to North Vietnamese fire, protecting other soldiers from a grenade blast and providing covering fire for American helicopters until he was killed.

Sabo was nominated for the Medal of Honor shortly after his death, but the records were lost. In 1999 a fellow Vietnam War veteran came across the records and began the process of reopening Sabo’s nomination. Following several delays, Sabo’s widow received the Medal of Honor from President Barack Obama on 16 May 2012, 42 years after his death.

Leslie Sabo, Jr. was born in Kufstein, Austria on 22 February 1948 to Elizabeth and Leslie Sabo, Sr., who had been members of an upper-class Hungarian family. Leslie Jr. had one brother, George, who was born in 1944, as well as a second brother who had been killed in World War II bombings at the age of one. With the post-World War II occupation of Hungary by the Soviet Union, Sabo’s family lost their fortune in the war and, upon realizing Communism would be installed in Hungary long-term, they left the country permanently.

The Sabo family moved to the United States in 1950 just after Sabo turned two years old. Leslie Sr., who had previously worked as a lawyer, attended evening classes to become an engineer in the United States. The family moved to Youngstown, Ohio and lived there for a short time before moving to Ellwood City, Pennsylvania, as Leslie Sr. followed a job at Blaw-Knox Corp. Growing up, Sabo’s father stressed discipline and patriotism. Sabo graduated from Lincoln High School in 1966 and briefly attended Youngstown State University before dropping out and working at a steel mill for a short time. He was described by friends and family as an affectionate and “kind-hearted hometown boy” who was easygoing and always in good humor. He enjoyed billiards and bowling.

Sabo in 1969 holding an M-60 Machine Gun.

Sabo was drafted into the United States Army April 1969 and sent to Fort Benning, GA for basic combat training. While on leave he married Rose Sabo-Brown (née Buccelli) the daughter of a World War II veteran and Silver Star recipient, whom he had met in 1967. He attended advanced individual training in September and October of that year, followed by a honeymoon trip to New York City, New York. Sabo was assigned to Bravo Company of the 3rd Battalion, 506th Infantry Regiment, U.S.A. 101st Airborne Division and was known to enjoy his time in the military, preferring the environment of discipline and camaraderie.

In January 1970 Sabo and his unit departed for Vietnam to fight in the Vietnam War and he began corresponding with his wife regularly via letter. The unit came into contact with North Vietnamese troops frequently for the first several months of its deployment, but most of these were small hit-and-run attacks. On 5 May 1970 Sabo’s platoon was attached to the U.S. 4th Infantry Division for a secret mission into Cambodia and dropped into the country on a UH-1 Huey helicopter. They were to conduct a series of interdiction missions against the Ho Chi Minh Trail with the assistance of heavy air support. For five days they came into constant, heavy contact with North Vietnamese forces that were often of superior size.

On 10 May 1970 Sabo’s platoon was part of a force of two platoons from Bravo Company on a mission to Se San, Cambodia. They were to engage a force of North Vietnamese Army (NVA) troops that had used the area as a staging ground for the Tet Offensive and other attacks. There they were ambushed by a force of 150 NVA troops hidden in the jungle and the trees, which had caught the American force in the open and unprepared. This battle became known as the “Mother’s Day ambush.” Sabo, who was at the column’s end, repeatedly repulsed efforts by the North Vietnamese to surround and overrun the Americans. As the battle continued, a North Vietnamese soldier threw a grenade near a wounded American soldier lying in the open. Sabo ran out from a small tree that had been providing him cover and draped himself over his wounded comrade as the grenade exploded. Then, after absorbing multiple wounds from the grenade blast, Sabo attacked the enemy trench, killing two soldiers with a grenade of his own, and helped his injured ally to the shelter of a nearby tree line. Later, with the Americans running out of ammunition, Sabo again exposed himself to retrieve rounds from Americans killed earlier in the day.

Sabo then began redistributing ammunition to other members of the platoon, including stripping ammunition from wounded and dead comrades. As night fell the North Vietnamese refocused their efforts from wiping out the American force to harassing the helicopters that were carrying more than two dozen wounded soldiers. As that was occurring, the remaining platoon from Bravo Company broke through the North Vietnamese lines and relieved the other two platoons while the first medical helicopter arrived and loaded two wounded soldiers under heavy fire. Sabo again stepped out into the open and provided covering fire for the helicopter until his ammunition was exhausted. He received several serious wounds under heavy fire by the North Vietnamese while trying to reload. Although mortally wounded, Sabo crawled forward toward the enemy emplacement, pulled the pin of a grenade, and threw it at the last possible second toward an enemy bunker. The resulting explosion silenced the enemy bunker at the cost of Sabo’s life. In all, seven other members of the platoon were killed in this ambush and another 28 were wounded. The North Vietnamese forces lost 49.

Although he was posthumously promoted to the rank of sergeant, the circumstances of Sabo’s death remained unclear to his family for several decades thereafter. Officially the military reported Sabo had been killed by a sniper while guarding an ammunition cache somewhere in Vietnam. Shortly after the action Sabo’s company commander, Captain Jim Waybright, recommended him for the Medal of Honor, but the accounts of Sabo’s actions and citation were lost for several decades. This changed in 1999 when Alton Mabb, another Vietnam War veteran of the 101st Airborne Division and a columnist for the division association magazine, uncovered the documents while at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. Mabb publicized Sabo’s exploits in the magazine and also wrote U.S. Congresswoman Corrine Brown, whom he asked to forward the recommendation. Brown lobbied the U.S. Department of Defense for Sabo to be recognized and, in 2006; Secretary of the Army Francis J. Harvey recommended that Sabo receive the Medal of Honor. Due to the delay in processing the citation, however, the award had to be approved by an act of Congress, so Brown attached it as a rider to a 2008 defense authorization bill. After continued delays in the process, however, Sabo’s family contacted U.S. Congressman Jason Altmire to push the award through the Defense Department. Secretary of the Army John McHugh recommended the Medal of Honor for Sabo in March 2010 and, on 16 April 2012, it was announced that Sabo’s family would receive the medal from U.S. President Barack Obama at a White House ceremony, 42 years after the action. Sabo posthumously received the Medal of Honor at the White House 16 May 2012, which was accepted by his widow. Sabo is interred at Holy Redeemer Cemetery in North Sewickley Township, Pennsylvania and is honored at a memorial to B Company in Marietta, Ohio, the home of his former commanding officer.

In addition to the Medal of Honor Sabo also received several other honors as well as being posthumously promoted to the rank of sergeant. His other military decorations include the Purple Heart Medal, the Air Medal, the Army Commendation Medal, the Army Good Conduct Medal, the Vietnam Gallantry Cross with Bronze Palm, and the Vietnam Campaign Medal. His unit awards include the Vietnam Gallantry Cross Unit Citation and the Vietnam Civil Actions Unit Citation.

Medal of Honor citation

Sabo was the 249th person to be awarded the Medal of Honor for actions in the Vietnam War and the 3,458th recipient in the history of the medal.

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty: Specialist Four Leslie H. Sabo Jr. distinguished himself by conspicuous acts of gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty at the cost of his own life while serving as a rifleman in Company B, 3d Battalion, 506th Infantry, 101st Airborne Division in Se San, Cambodia, on May 10, 1970. On that day, Specialist Four Sabo and his platoon were conducting a reconnaissance patrol when they were ambushed from all sides by a large enemy force. Without hesitation, Specialist Four Sabo charged an enemy position, killing several enemy soldiers. Immediately thereafter, he assaulted an enemy flanking force, successfully drawing their fire away from friendly soldiers and ultimately forcing the enemy to retreat. In order to re-supply ammunition, he sprinted across an open field to a wounded comrade. As he began to reload, an enemy grenade landed nearby. Specialist Four Sabo picked it up, threw it, and shielded his comrade with his own body, thus absorbing the brunt of the blast and saving his comrade’s life. Seriously wounded by the blast, Specialist Four Sabo nonetheless retained the initiative and then single-handedly charged an enemy bunker that had inflicted severe damage on the platoon, receiving several serious wounds from automatic weapons fire in the process. Now mortally injured, he crawled towards the enemy emplacement and, when in position, threw a grenade into the bunker. The resulting explosion silenced the enemy fire, but also ended Specialist Four Sabo’s life. His indomitable courage and complete disregard for his own safety saved the lives of many of his platoon members. Specialist Four Sabo’s extraordinary heroism and selflessness, above and beyond the call of duty, at the cost of his life, are in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself, Company B, 3d Battalion, 506th Infantry, 101st Airborne Division, and the United States Army.

Recent Comments