Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 14

Born: 22 February 1948 Kufstein, Austria

Died: 10 May 1970 (aged 22) Se San, Cambodia

Place of burial: North Sewickley Township, Beaver County, Pennsylvania

Allegiance: United States of America

Service/branch: United States Army

Years of service: 1969–1970

Rank: Sergeant (posthumous)

Unit: 506th Infantry Regiment

Battles/wars: Vietnam War: Cambodian Campaign

Awards: Medal of Honor; Bronze Star; Purple Heart; Air Medal

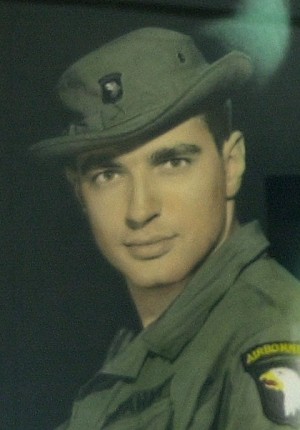

Leslie Halasz Sabo, Jr. (Hungarian: ifj. Halász Szabó László) (22 February 1948 – 10 May 1970) was a soldier in the United States Army during the Vietnam War. He received the highest military decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his actions during the Cambodian Campaign in 1970.

Born in Kufstein, Austria, Sabo’s family immigrated to the United States when he was young and moved to Ellwood City, Pennsylvania. Sabo dropped out of college and was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1969, becoming a member of the 506th Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. On 10 May 1970 Sabo’s unit was on an interdiction mission near Se San, Cambodia when they were ambushed from all sides by the Vietnam People’s Army. Sabo repeatedly exposed himself to North Vietnamese fire, protecting other soldiers from a grenade blast and providing covering fire for American helicopters until he was killed.

Sabo was nominated for the Medal of Honor shortly after his death, but the records were lost. In 1999 a fellow Vietnam War veteran came across the records and began the process of reopening Sabo’s nomination. Following several delays, Sabo’s widow received the Medal of Honor from President Barack Obama on 16 May 2012, 42 years after his death.

Leslie Sabo, Jr. was born in Kufstein, Austria on 22 February 1948 to Elizabeth and Leslie Sabo, Sr., who had been members of an upper-class Hungarian family. Leslie Jr. had one brother, George, who was born in 1944, as well as a second brother who had been killed in World War II bombings at the age of one. With the post-World War II occupation of Hungary by the Soviet Union, Sabo’s family lost their fortune in the war and, upon realizing Communism would be installed in Hungary long-term, they left the country permanently.

The Sabo family moved to the United States in 1950 just after Sabo turned two years old. Leslie Sr., who had previously worked as a lawyer, attended evening classes to become an engineer in the United States. The family moved to Youngstown, Ohio and lived there for a short time before moving to Ellwood City, Pennsylvania, as Leslie Sr. followed a job at Blaw-Knox Corp. Growing up, Sabo’s father stressed discipline and patriotism. Sabo graduated from Lincoln High School in 1966 and briefly attended Youngstown State University before dropping out and working at a steel mill for a short time. He was described by friends and family as an affectionate and “kind-hearted hometown boy” who was easygoing and always in good humor. He enjoyed billiards and bowling.

Sabo in 1969 holding an M-60 Machine Gun.

Sabo was drafted into the United States Army April 1969 and sent to Fort Benning, GA for basic combat training. While on leave he married Rose Sabo-Brown (née Buccelli) the daughter of a World War II veteran and Silver Star recipient, whom he had met in 1967. He attended advanced individual training in September and October of that year, followed by a honeymoon trip to New York City, New York. Sabo was assigned to Bravo Company of the 3rd Battalion, 506th Infantry Regiment, U.S.A. 101st Airborne Division and was known to enjoy his time in the military, preferring the environment of discipline and camaraderie.

In January 1970 Sabo and his unit departed for Vietnam to fight in the Vietnam War and he began corresponding with his wife regularly via letter. The unit came into contact with North Vietnamese troops frequently for the first several months of its deployment, but most of these were small hit-and-run attacks. On 5 May 1970 Sabo’s platoon was attached to the U.S. 4th Infantry Division for a secret mission into Cambodia and dropped into the country on a UH-1 Huey helicopter. They were to conduct a series of interdiction missions against the Ho Chi Minh Trail with the assistance of heavy air support. For five days they came into constant, heavy contact with North Vietnamese forces that were often of superior size.

On 10 May 1970 Sabo’s platoon was part of a force of two platoons from Bravo Company on a mission to Se San, Cambodia. They were to engage a force of North Vietnamese Army (NVA) troops that had used the area as a staging ground for the Tet Offensive and other attacks. There they were ambushed by a force of 150 NVA troops hidden in the jungle and the trees, which had caught the American force in the open and unprepared. This battle became known as the “Mother’s Day ambush.” Sabo, who was at the column’s end, repeatedly repulsed efforts by the North Vietnamese to surround and overrun the Americans. As the battle continued, a North Vietnamese soldier threw a grenade near a wounded American soldier lying in the open. Sabo ran out from a small tree that had been providing him cover and draped himself over his wounded comrade as the grenade exploded. Then, after absorbing multiple wounds from the grenade blast, Sabo attacked the enemy trench, killing two soldiers with a grenade of his own, and helped his injured ally to the shelter of a nearby tree line. Later, with the Americans running out of ammunition, Sabo again exposed himself to retrieve rounds from Americans killed earlier in the day.

Sabo then began redistributing ammunition to other members of the platoon, including stripping ammunition from wounded and dead comrades. As night fell the North Vietnamese refocused their efforts from wiping out the American force to harassing the helicopters that were carrying more than two dozen wounded soldiers. As that was occurring, the remaining platoon from Bravo Company broke through the North Vietnamese lines and relieved the other two platoons while the first medical helicopter arrived and loaded two wounded soldiers under heavy fire. Sabo again stepped out into the open and provided covering fire for the helicopter until his ammunition was exhausted. He received several serious wounds under heavy fire by the North Vietnamese while trying to reload. Although mortally wounded, Sabo crawled forward toward the enemy emplacement, pulled the pin of a grenade, and threw it at the last possible second toward an enemy bunker. The resulting explosion silenced the enemy bunker at the cost of Sabo’s life. In all, seven other members of the platoon were killed in this ambush and another 28 were wounded. The North Vietnamese forces lost 49.

Although he was posthumously promoted to the rank of sergeant, the circumstances of Sabo’s death remained unclear to his family for several decades thereafter. Officially the military reported Sabo had been killed by a sniper while guarding an ammunition cache somewhere in Vietnam. Shortly after the action Sabo’s company commander, Captain Jim Waybright, recommended him for the Medal of Honor, but the accounts of Sabo’s actions and citation were lost for several decades. This changed in 1999 when Alton Mabb, another Vietnam War veteran of the 101st Airborne Division and a columnist for the division association magazine, uncovered the documents while at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. Mabb publicized Sabo’s exploits in the magazine and also wrote U.S. Congresswoman Corrine Brown, whom he asked to forward the recommendation. Brown lobbied the U.S. Department of Defense for Sabo to be recognized and, in 2006; Secretary of the Army Francis J. Harvey recommended that Sabo receive the Medal of Honor. Due to the delay in processing the citation, however, the award had to be approved by an act of Congress, so Brown attached it as a rider to a 2008 defense authorization bill. After continued delays in the process, however, Sabo’s family contacted U.S. Congressman Jason Altmire to push the award through the Defense Department. Secretary of the Army John McHugh recommended the Medal of Honor for Sabo in March 2010 and, on 16 April 2012, it was announced that Sabo’s family would receive the medal from U.S. President Barack Obama at a White House ceremony, 42 years after the action. Sabo posthumously received the Medal of Honor at the White House 16 May 2012, which was accepted by his widow. Sabo is interred at Holy Redeemer Cemetery in North Sewickley Township, Pennsylvania and is honored at a memorial to B Company in Marietta, Ohio, the home of his former commanding officer.

In addition to the Medal of Honor Sabo also received several other honors as well as being posthumously promoted to the rank of sergeant. His other military decorations include the Purple Heart Medal, the Air Medal, the Army Commendation Medal, the Army Good Conduct Medal, the Vietnam Gallantry Cross with Bronze Palm, and the Vietnam Campaign Medal. His unit awards include the Vietnam Gallantry Cross Unit Citation and the Vietnam Civil Actions Unit Citation.

Medal of Honor citation

Sabo was the 249th person to be awarded the Medal of Honor for actions in the Vietnam War and the 3,458th recipient in the history of the medal.

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty: Specialist Four Leslie H. Sabo Jr. distinguished himself by conspicuous acts of gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty at the cost of his own life while serving as a rifleman in Company B, 3d Battalion, 506th Infantry, 101st Airborne Division in Se San, Cambodia, on May 10, 1970. On that day, Specialist Four Sabo and his platoon were conducting a reconnaissance patrol when they were ambushed from all sides by a large enemy force. Without hesitation, Specialist Four Sabo charged an enemy position, killing several enemy soldiers. Immediately thereafter, he assaulted an enemy flanking force, successfully drawing their fire away from friendly soldiers and ultimately forcing the enemy to retreat. In order to re-supply ammunition, he sprinted across an open field to a wounded comrade. As he began to reload, an enemy grenade landed nearby. Specialist Four Sabo picked it up, threw it, and shielded his comrade with his own body, thus absorbing the brunt of the blast and saving his comrade’s life. Seriously wounded by the blast, Specialist Four Sabo nonetheless retained the initiative and then single-handedly charged an enemy bunker that had inflicted severe damage on the platoon, receiving several serious wounds from automatic weapons fire in the process. Now mortally injured, he crawled towards the enemy emplacement and, when in position, threw a grenade into the bunker. The resulting explosion silenced the enemy fire, but also ended Specialist Four Sabo’s life. His indomitable courage and complete disregard for his own safety saved the lives of many of his platoon members. Specialist Four Sabo’s extraordinary heroism and selflessness, above and beyond the call of duty, at the cost of his life, are in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself, Company B, 3d Battalion, 506th Infantry, 101st Airborne Division, and the United States Army.

Have We Forgotton Our Heroes? Chapter 10

Name: Lance Peter Sijan

Rank/Branch: O2/USAF

Date of Birth: 13 April 1942

Home City of Record: Milwaukee WI

Date of Loss: 09 November 1967

Country of Loss: Laos

Loss Coordinates: 171500N 1060800E

Status (In 1973): Killed in Captivity

Category: 1

Acft/Vehicle/Ground: F4C

Lance Peter Sijan, born 13 April 1942, was the son of Sylvester and Jane (Attridge) Sijan of Milwaukee, WI. The following are excerpts from the “Airman” Magazine.

CPT Lance P. Sijan was the first Air Force Academy graduate to receive the Medal of Honor.

THE CODE OF CONDUCT

ARTICLE I – I am an American fighting man. I serve in the forces which guard my country and our way of life. I am prepared to give my life in their defense.

The colonel, recalling the tragic events of almost nine years earlier, had been talking for more than an hour about the heroic ordeal of Capt. Lance P. Sijan, his cellmate in North Vietnam. Reaching the point in his chronology when Sijan, calling out helplessly for his father, was taken away by his captors to die, Col. Bob Craner’s voice broke ever so slightly and tears glistened in his eyes. He agreed to a recess in the interview.

THE CODE OF CONDUCT

ARTICLE II – I will never surrender of my own free will. If in command, I will never surrender my men while they still have the means to resist.

“Okay Mom, you can come back in now!”

The voice, coming from a tape recorder that day in early November 1967, gave immense pleasure to Mr. and Mrs. Sylvester Sijan (pronounced sigh-john), just as it had so many times for more than 25 years. It was especially meaningful now, coming from Da Nang AB, Vietnam. Their son had done his Christmas shopping early and, separated by half a world, was having some mischievous fun with his family.

Sitting in the living room of the comfortable two-story house in Milwaukee, Mrs. Jane Sijan tenderly related the tale of her son’s tape. Across the street, snow was crusted on the park that gently slopes into Lake Michigan. Flames danced in the fireplace as Sylvester Sijan busily prepared to show movies of Lance’s graduation from the Air Force Academy in 1965.

Everywhere was memorabilia of Lance and his brother, Marc, younger by five years, and his sister, Janine, 13 years Lance’s junior. An oil painting bathed in soft neon light on one wall showed Lance in his academy uniform, smiling out into the room.

Along the staircase hung dozens of photos of the Sijans–their children, relatives and friends. Football pictures of Lance and Marc abounded, for football is a tradition with the Sijans. Lance’s Bay View High School team won the city championship in 1959, the first time Bay View had turned the trick since 1936, when Lance’s father played on the team. Family heirlooms, souvenirs from faraway places, and trophies dominated mantels and shelves. The most significant showpiece, however, was enshrined in a glass case. Resplendent with its accompanying baby-blue ribbon dotted with tiny white stars was Capt. Lance Sijan’s Medal of Honor. It had been awarded posthumously.

Jane Sijan–attractive and dark-haired, her Irish heritage smiling through–continued her story of the tape from Vietnam: “Lance made us individually leave the room as he described the Christmas presents he had gotten for us. He’d say, ‘Mom, leave the room,’ and then he’d tell everybody what he had for me. Then he’d yell for me to come back in, and he’d send someone else out.”

Those Christmas presents were not opened that year, nor for several years thereafter. On Nov. 9, 1967, Capt. Lance Sijan was shot down over North Vietnam. For years no one at home knew his fate. The box of Christmas presents was added to his personal effects, and not until his body was returned to Milwaukee some seven years later did his family sort through his belongings.

On March 4, 1976, President Gerald R. Ford awarded the Medal of Honor to Sijan for his “extraordinary heroism and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty at the cost of his life. . . .”

THE CODE OF CONDUCT

ARTICLE III – If am I captured I will continue to resist by all means available. I will make every effort to escape and aid others to escape. I will accept neither parole nor special favors from the enemy.

R&R in Bangkok, Thailand, had been nostalgic for Lance Sijan. He told his family in a tape from the country once known as Siam that his drama teacher at Bay View High School–where Sijan had been president of the Student Government Association and received the Gold Medal Award for outstanding leadership, achievement, and service–would have been impressed. As a sophomore, according to his mother, Lance had competed against seniors for the lead singing role in the school production of “The King and I,” which was set in Siam. Competition raged for six weeks, consuming Lance’s energy and concern.

“One day,” said Jane, “he walked in and said, ‘Well, I’d like to speak to the Queen Mother.’ I knew he had the part.”

There were 21 children in the cast, and Sijan needed one special little princess. He and Marc had always doted over their sister, Janine, even to the point of arguing who would feed her, as an infant, in the middle of the night. Lance asked Janine, then not quite 4 years old, to be his daughter in the play. Occasionally, the family listens to a recording of the play, Lance’s rich voice sing-talking the role of the Siamese king that Yul Brynner made famous.

Sijan flew his first post-R&R mission on Nov. 9, 1967, as the pilot of an F-4 with Col. John W. Armstrong, commander of the 366th Tactical Fighter Squadron, as the backseater. On a bombing pass over North Vietnam near Laos, their aircraft was hit and exploded. Armstrong was never heard from again. Sijan, plummeting to the ground after a low-level bailout, suffered a skull fracture, a mangled right hand with three fingers bent backward to the wrist, and a compound fracture of his left leg, the bone protruding through the lacerated skin.

The ordeal of Lance Sijan–big, strong, tough, handsome, a football player at the Air Force Academy, remembered as a fierce competitor by those who knew him–had begun. He would live in the North Vietnamese jungle with no food and little water for some 45 days. Virtually immobilized, he would propel himself backward on his elbows and buttocks toward what he hoped was freedom. He was alone. He would be joined later by two other Americans, and in short, fading, in-and-out periods of consciousness and lucidity, would tell them his story.

Now, however, there was hope for Lance Sijan. Aircraft circled and darted overhead, part of a gigantic search-and-rescue effort launched to recover him and Armstrong. Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Service histories state that 108 aircraft participated the first two days, and 14 more on the third when no additional contact was made with Sijan, known to those above as “AWOL 1.”

the third when no additional contact was made with Sijan, known to those above as “AWOL 1.”

Contact had been made earlier, and the answer to the authenticating question, “Who is the greatest football team in the world?” came easily for the Wisconsin native. “The Green Bay Packers,” Sijan replied. In continuing voice contacts, “the survivor was talking louder and faster,” the history notes. “AWOL did not know what happened to the backseater.”

The rescue force, meanwhile, was taking “ground fire from all directions” and was “worried about all the [friendly] fire hitting the survivor.” Finally, Jolly Green 15, an HH-3E helicopter, picked up a transmission from the ground: “I see you, I see you. Stay where you are. I’m coming to you!”.

For 33 minutes, Jolly Green 15 hovered over the jungle, eyes aboard searching the dense foliage below for movement. Bullets began piercing the fuselage, a few at first and then more and more. Getting no more voice contact from the ground and under a withering hail of fire, Jolly Green 15 finally left the area.

Rescue efforts the next day and electronic surveillance in the days that followed turned up no more contacts, and the search for “AWOL” was called off. One A-1E aircraft was shot down in the effort–the pilot was rescued–and several helicopter crewmen were wounded.

“If AWOL,” said the report, “only had some kind of signaling device– mirror, flare, etc.–pick-up would have been successful. The rescue of this survivor was not in the hands of man.”

Much later, a battered Lance Sijan was to ask his American cellmates, “What did I do wrong? Why didn’t I get picked up?” He told them he had lost his survival kit.

On that November day, except for enemy forces all around, Sijan was alone again. Although desperately in need of food, water and medical attention, he somehow evaded the enemy and capture as he painfully, day by day, dragged himself along the ground–toward, he hoped, freedom. But it was not to be.

Former Capt. Guy Gruters, who was to be one of Sijan’s cellmates later, told Airman: “He said he’d go for two or three days and nights–as long as he possibly could–and then he’d be exhausted and sleep. As soon as he’d wake up he’d start again, always traveling east. You’re talking 45 days now without food, and it was a max effort!”

Col. Bob Craner, the older cellmate in Hanoi, picked up the story: “When he couldn’t drag himself anymore and said, ‘This is the end,’ he saw he was on a dirt road. He lay there for a day, maybe, until a truck came along and they picked him up.

Incredibly, after a month and a half of clawing, clutching, dragging and hurting, Sijan was found three miles from where he had initially parachuted into the jungle.

Horribly emaciated and with the flesh of his buttocks worn to his hip bones, Lance Sijan still had some fight left. “He said they took him to a place where they laid him on a mat and gave him some food,” Craner related. “He said he waited until he felt he was getting a little stronger. When there was just one guard there, Captain Sijan beckoned him over. When the guy bent over to see what was the matter, Captain Sijan told me, ‘I just let him have it–wham!’ ” With the guard unconscious from a well-placed karate chop from a weakened left arm and hand, Sijan pulled himself back into the jungle. “He thought he was making it,” Craner said, “but they found him after a couple of hours.”

Once again Sijan had been robbed of precious freedom. Once again he was down, but–as other North Vietnamese were to learn–by no means out.

THE CODE OF CONDUCT

ARTICLE IV – If I become a prisoner of war, I will keep faith with my fellow prisoners. I will give no information or take part in any action which might be harmful to my comrades. If I am senior, I will take command. If not, I will obey the lawful orders of those appointed over me and will back them up in every way.

Sijan’s obsession with freedom had manifested itself much earlier, and rather uniquely, at the Air Force Academy. His arts instructor, Col. Carlin J. Kielcheski, remembers him well. “He had the crusty facade of a football player, yet he was very sensitive. I was particularly interested in those guys who broke the image of the typical artist.”

Kielcheski still has the “Humanities 499” paper Sijan submitted with his two-foot wooden sculpture of a female dancer. Sijan wrote:

“I feel that the female figure is one of nature’s purest forms. I want this statue to represent the quest for freedom by the lack of any restraining devices or objects. The theme of my sculpture is just that–a quest for freedom, an escape from the complexities of the world around us.”

Kielcheski chuckled. “Here was this bruiser of a football player coming up with these delicate kinds of things. He was not content to do what the other cadets did. He was very persistent and not satisfied with doing just any kind of job. He wanted to do it right and showed real tenacity to stick to a problem.”

Others remember different aspects of Sijan’s character. His roommate for three years, Mike Smith of Denver, said he was “probably the toughest guy mentally I’ve ever met.”

Sijan was a substitute end on the football team, Smith said. Football, he thought, hindered his academics, and his concern over grades conversely affected his performance and chances for stardom on the gridiron. “He had a lot of things going and tried to keep them all going. He came in from football practice dead tired. He’d sleep for an hour or two after dinner and then study until 1 or 2 in the morning. He knew he had to give up a lot to play football, but he had the determination to do it.”

Sijan did give up football his senior year. But one thing he did not sacrifice for studies was the company of young women.

They found him very attractive, and he had no trouble getting dates,” said Smith. “He was a big, hand some guy with a good sense of humor.” Maj. Joe Kolek, who roomed with Sijan one semester, agreed. In fact, he said, “It was pretty neat now and then to get Lance’s cast-offs.”

Smith recalls they talked sometimes about the Code of Conduct that was to test Sijan’s character so severely fewer than three years later. We found nothing wrong with the Code. We accepted the responsibility of action honorable to our country. It was strictly an extension of Lance’s personality. When he accepted something, he accepted it. He did nothing halfway. It seemed,” Smith said, “that there was always a reservoir of strength he got from his family.”

Sylvester Sijan, whose character and physique bear a striking resemblance to a middle-aged Jack Dempsey, owns the Barrel Head Grille in Milwaukee. Built into an inside wall is a mock 4-feet-around beer barrel top, a splendid woodwork fashioned by the elder Sijan from an oak table. A wooden shingle on the polished oak bears the engraved inscription, “Tradition.”

Sylvester Sijan’s forefathers immigrated from Serbia, a separate country prior to World War I that later became part of Yugoslavia. “Serbians have been noted for their heroic actions in circumstances where they were outnumbered,” the elder Sijan said. “They were vicious fighters on a one-to-one or a one-to-fifty basis, so they have a history of instinct and drive.” He thinks a mixture of that tradition, his son’s love for his home and his competitive spirit spurred him through the painful odyssey in Vietnam. What made Lance do what he did? One thing, for sure. He always wanted to come home, no matter where he was. He was going to come home whether it was in pieces or as a hero.

“Lance’s competitive nature kind of grew with him,” said Sylvester Sijan. “A person never knows how competitive he really is until he comes up against the ultimate situation. He could have been less courageous; he could have retreated into the ranks of the North Vietnamese and said, ‘Here I am, take care of me.’ But he chose to go the other way. He probably never doubted that somehow, somewhere he’d get out.”

Lance Sijan had wondered about his ultimate fate even before leaving for Vietnam, according to Mike Smith. In the Air Force at the time and stationed at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio, Smith enjoyed a visit from Sijan, who was on leave prior to going overseas. “I sensed a foreboding in him, and he and I dealt with the issue of not coming back,” Smith said. “I remember it distinctly because I talked with my wife about our conversation. I felt he had a premonition that he might not return.”

Jane Sijan, too, sensed something. In Milwaukee prior to leaving, Lance asked her to sew two extra pockets into his flight suit, and he took great pains coating matches with wax. “One night he was sitting on his bed,” she recalled. “He was sewing razor blades into his undershirts so he would have them if he was ever shot down.”

THE CODE OF CONDUCT

ARTICLE V – When questioned, should I become a prisoner of war, I am required to give name, rank, service number, and date of birth. I will evade answering further questions to the utmost of my ability. I will make no oral or written statements disloyal to my country and its allies or harmful to their cause.

Capt. Lance Sijan had been on the ground for 41 days when Col. Bob Craner and Capt. Guy Gruters took off from Phu Cat AB in their F-100 on Dec. 20, 1967. Pinpointing targets in North Vietnam from the “Misty” forward air control jet fighter, they were hit by ground fire and ejected. Both were captured and brought to a holding point in Vinh, where they were thrust into bamboo cells and chained.

Reaching back into his memory, crowded with recollections of more than five years as a prisoner of war, Craner told the story: “As best as I can recall, it was New Year’s Day of 1968 when they brought this guy in at night. The Rodent [a prison guard] came into the guy’s cell next to mine and began his interrogation. It was clearly audible. “He was on this guy for military information, and the responses I heard indicated he was in very, very bad shape. His voice was very weak. It sounded to me as though he wasn’t going to make it.

“The Rodent would say, ‘Your arm, your arm, it is very bad. I am going to twist it unless you tell me.’ The guy would say, ‘I’m not going to tell you; it’s against the Code.’ Then he would start screaming. The Rodent was obviously twisting his mangled arm. The whole affair went on for an hour and a half, over and over again, and the guy just wouldn’t give in. He’d say, ‘Wait till I get better, you S.O.B., you’re really going to get it.’ He was giving the Rodent all kinds of lip, but no information. “The Rodent kept laying into him. Finally I heard this guy rasp, ‘Sijan! My name is Lance Peter Sijan!’ That’s all he told him.”

Guy Gruters, also an Air Force Academy graduate, but a year senior to Sijan, was in a cell down the hall and did not know the identity of the third captive. He does recall that “the guy was apparently always trying to push his way out of the bamboo cell, and they’d beat him with a stick to get him back. We could hear the cracks.” After several days, when the North Vietnamese were ready to transport the Americans to Hanoi, Gruters and Craner were taken to Sijan’s cell to help him to the truck. “When I got a look at the poor devil, I retched,” said Craner. “He was so thin and every bone in his body was visible. Maybe 20 percent of his body wasn’t open sores or open flesh. Both hip bones were exposed where the flesh had been worn away.” Gruters recalled that he looked like a little guy. But then when we picked him up, I remember commenting to Bob, ‘This is one big sonofagun.”‘

While they were moving him, Craner related, “Sijan looked up and said, ‘You’re Guy Gruters, aren’t you?”

Gruters asked him how he knew, and Sijan replied, “We were at the academy together. Don’t you know me? I’m Lance Sijan.” Guy went into shock. He said, “My God, Lance, that’s not you!” “I have never had my heart-broken like that,” said Gruters, who remembered Sijan as a 220-pound football player at the academy. “He had no muscle left and looked so helpless.”

Craner said Sijan never gave up on the idea of escape in all the days they were together. “In fact, that was one of the first things he mentioned when we first went into his cell at Vinh: ‘How the hell are we going to get out of here? Have you guys figured out how we’re going to take care of these people? Do you think we can steal one of their guns?’

“He had to struggle to get each word out,” Craner said. “It was very, very intense on his part that the only direction he was planning was escape. That’s all that was on his mind. Even later, he kept dwelling on the fact that he’d made it once and he was going to make it again.” Craner remembers the Rodent coming up to them and, in a mocking voice, he paraphrased the Rodent’s message:

“Sijan a very difficult man. He struck a guard and injured him. He ran away from us. You must not let him do that anymore.”

“I never questioned the fact that Lance would make it,” said Gruters. “Now that he had help, I thought he’d come back. He had passed his low.”

The grueling truck ride to Hanoi took several days. Sijan–“in and out of consciousness, lucid for 15 seconds sometimes and sometimes an hour, but garbled and incoherent a lot,” according to Craner–told the story of his 45-day ordeal in the jungle while the trio were kept under a canvas cover during the day. The truck ride over rough roads at night, with the Americans constantly bouncing 18 inches up and down in the back, was torture itself. Craner and Gruters took turns struggling to keep an unsecured 55-gallon drum of gasoline from smashing them while the other cradled Sijan between his legs and cushioned his head against the stomach. “I thought he had died at one point in the trip,” said Craner. “I looked at Guy and said, ‘He’s dead.’ Guy started massaging his face and neck trying to bring him around. Nothing. I sat there holding him for about two hours, and suddenly he just came around. I said, ‘OK, buddy, my hat’s off to you.”‘

Finally reaching Hanoi, the three were put into a cell in “Little Vegas.” Craner described the conditions: “It was dark, with open air, and there was a pool of water on the worn cement floor. It was the first time I suffered from the cold. I was chilled to the bone, always shivering and shaking. Guy and I started getting respiratory problems right away, and I couldn’t imagine what it was doing to Lance. That, I think, accounts ultimately for the fact that he didn’t make it.”

“Lance was always as little of a hindrance to us as he could be,” said Gruters. “He could have asked for help any one of a hundred thousand times, but he never asked for a damned thing! There was no way Bob and I could feel sorry for ourselves.”

Craner said a Vietnamese medic gave Sijan shots of yellow fluid, which he thought were antibiotics. The medic did nothing for his open sores and wounds, and when he looked at Sijan’s mangled hand, “he just shook his head.” The medic later inserted an intravenous tube into Sijan’s arm, but Sijan, fascinated with it in his subconscious haze, pulled it out several times. Thus, Craner and Gruters took turns staying awake with him at night.

“One night,” the colonel said, “a guard opened the little plate on the door and looked in, and there was Lance beckoning to the guard. It was the same motion he told me he had made to the guy in the jungle, and I could just see what was going through the back reaches of his mind: ‘If I can just get that guy close enough. . . .”‘ He remembers that Sijan once asked them to help him exercise so he could build up his strength for another escape attempt. “We got him propped up on his cot and waved his arms around a few times, and that satisfied him. Then he was exhausted.” At another point, Sijan became lucid enough to ask Craner, “How about going out and getting me a burger and french fries?” But Sijan’s injuries and now the respiratory problem sapped his strength. “First he could only whisper a word, and then it got down to blinking out letters with his eyes,” said Gruters. “Finally he couldn’t do that anymore, even a yes or no.”

With tears glistening, Bob Craner remembered when it all came to an end. They had been in Hanoi about eight days. “One night Lance started making strangling sounds, and we got him to sit up. Then, for the first time since we’d been together, his voice came through loud and clear. He said, ‘Oh my God, it’s over,’ and then he started yelling for his father. He’d shout, ‘Dad, Dad, where are you? Come here, I need you!’

“I knew he was sinking fast. I started beating on the walls, trying to call the guards, hoping they’d take him to a hospital. They came in and took him out. As best as I could figure it was January 21.” “He had never asked for his dad before,” said Gruters, “and that was the first time he’d talked in four or five days. It was the first time I saw him display any emotion. It was absolutely his last strength.

It was the last time we saw him.” A few days later, Craner met the camp commander in the courtyard while returning from a bathhouse and asked him where Sijan was. “Sijan spend too long in the jungle,” came the reply. “Sijan die.”

Guy Gruters talked some more about Sijan: “He was a tremendously strong, tough, physical human being. I never heard Lance complain. If you had an army of Sijans, you’d have an incredible fighting force.”

Said Craner: “Lance never talked about pain. He’d yell out in pain sometimes, but he’d never dwell on it like, ‘Damn, that hurts.’ “Lance was so full of drive whenever he was lucid. There was never any question of, ‘I hurt so much that I’d rather be dead.’ It was always positive for him, pointed mainly toward escape but always toward the future.”

Craner recommended Sijan for the Medal of Honor. Why? “He survived a terrible ordeal, and he survived with the intent, sometime in the future, of picking up the fight. Finally he just succumbed.” “There is no way you can instill that kind of performance in an individual. l don’t know how many we’re turning out like Lance Sijan, but I can’t believe there are very many.”

THE CODE OF CONDUCT

ARTICLE VI – I will never forget that I am an American fighting man, responsible for my actions, and dedicated to the principles which made my country free. I will trust in my God and in the United States of America.

In Milwaukee, Sylvester Sijan started to bring up the point, and then he hesitated. He finally did, though, and then he talked about it unabashedly. “I remember one day in January, about the same time that year, driving down the expressway; I was feeling despondent, and I began screaming as loud as I could, things like, ‘Lance, where are you?’ I may have murmured such things to myself before, but I never yelled as loud as I did that day.” He wonders if maybe–just maybe–it may have been at the same time Lance was calling for him in Hanoi. “The realization that Lance’s final thoughts were what they were makes me feel most humble, most penitent, and yet somehow profoundly honored,” he said. He still wears a POW bracelet with Lance’s name on it. “I just can’t take it off,” he said, adding that “not too many people realize its significance anymore.”

Though Lance was declared missing in action, and though one package they sent to him in Hanoi came back stamped “deceased”–“which jarred me terribly,” Jane Sijan said–the family never gave up hope. “I’m such an optimist,” she said. “I even watched all the prisoners get off the planes on television [in 1973] hoping there had been some mistake.”

Lance’s body, along with the headstone used to mark his grave in North Vietnam, was returned to the United States in 1974 for interment in Milwaukee (23 other bodies were returned to the United States at the same time). At a memorial service in Bay View High School, the family announced the Captain Lance Peter Sijan Memorial Scholarship Fund.

“It is a $500 scholarship presented yearly to a graduate male student best exemplifying Lance’s example of the American boy,” said Jane. “It will be a lifetime effort on our behalf and will be carried on by our children.”

Lance Sijan, U.S. Air Force Academy Class of 1965, would be 72 years old now. He is the first academy graduate to be awarded the Medal of Honor. A dormitory at the academy was named Sijan Hall in his honor. “The man represented something,” Sylvester Sijan said of his son. “The old cliche that he was a hero and represented guts and determination is true. That’s what he really represented. How much of that was really Lance? What he is, what he did, the facts are there.” “We’ll never adjust to it,” he said. “People say, ‘It’s been a long time ago and you should be OK now,’ but it stays with you and well it should.”

“Lance was always such a pleasure; he was an ideal son, but then all our children are a joy and blessing to us,” said Jane Sijan. “It still hurts to talk about it, but I have certainly accepted it. I’m a very patient woman, and I wait for the day our family will all be together again, that’s all.”

On March 4, 1976, three other former prisoners of war, all living, also received Medals of Honor from President Ford. One of them was Air Force Col. George E. “Bud” Day [“All Day’s Tomorrows,” Airman, November 1976]. Col. Day later wrote to Airman: “Lance was the epitome of dedication, right to death! When people ask about what kind of kids we should start with, the answer is: straight, honest kids like him. They will not all stay that way–but by God, that’s the minimum to start with.”

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 9

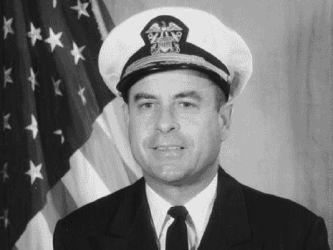

Name: James Bond Stockdale

Rank/Branch: O5/US Navy, pilot

Unit: CAG 16, USS ORISKANY (CVA 34)

Date of Birth: 23 December 1923

Home City of Record: Abingdon IL

Date of Loss: 09 September 1965

Country of Loss: North Vietnam

Loss Coordinates: 193400N 1065800E (WG839635)

Status (in 1973): Released POW

Aircraft/Vehicle/Ground: A4E

Missions: 202+

By midsummer 1964 events were taking place in the Gulf of Tonkin that would lead to the first clash between U.S. and North Vietnamese forces. In late July the destroyer USS MADDOX, on patrol in the gulf gathering intelligence had become the object of communist attention. For two consecutive days, 31 July-1 August, the MADDOX cruised unencumbered along a pre-designated route off the North Vietnamese coast. In the early morning hours of 2 August, however, it was learned from intelligence sources of a possible attack against the destroyer. The attack by three North Vietnamese P-4 torpedo boats (PT boats) materialized just after 4:00 p.m. on August 2. The MADDOX fired off three warning volleys, then opened fire. Four F-8 Crusaders led by Commander James B. Stockdale from the aircraft carrier USS TICONDEROGA, also took part in the skirmish. The result of the twenty-minute affair saw one gunboat sunk and another crippled. The MADDOX, ordered out of the gulf after the incident concluded, was hit by one 14.5mm shell.

A day later the MADDOX accompanied by the destroyer USS C. TURNER JOY, received instructions to re-enter the gulf and resume patrol. The USS CONSTELLATION, on a Hong Kong port visit was ordered to join the TICONDEROGA stationed at the mouth of the gulf in the South China Sea. The two destroyers cruised without incident on August 3 and in the daylight hours of August 4 moved to the middle of the gulf. Parallel to the movements of the C. TURNER JOY and MADDOX, South Vietnamese gunboats launched attacks on several North Vietnamese radar installations. The North Vietnamese believed the U.S. destroyers were connected with these strikes. At 8:41 p.m. on August 4 both destroyers reportedly picked up fast-approaching contacts on their radars. Navy documents show the ships changed course to avoid the unknown vessels, but the contacts continued intermittently. At 10:39 p.m. when the MADDOX and C. TURNER JOY radars indicated one enemy vessel had closed to within seven thousand yards, the C. TURNER JOY was ordered to open fire and the MADDOX soon followed. For the next several hours, the destroyers, covered by the TICONDEROGA’s and the CONSTELLATION’s aircraft, reportedly evaded torpedoes and fired on their attackers.

Historians have debated, and will continue to do so, whether the destroyers were actually ever attacked. Most of the pilots flying that night spotted nothing. Stockdale, who would later earn the Medal of Honor, stated that a gunboat attack did not occur. The skipper of the TICONDEROGA’s Attack Squadron 56, Commander Wesley L. McDonald, said he “didn’t see anything that night except the MADDOX and the TURNER JOY.”

President Lyndon B. Johnson reacted at once to the supposed attacks on the MADDOX, ordering retaliatory strikes on strategic points in North Vietnam. Even as the President spoke to the nation, aircraft from the CONSTELLATION and TICONDEROGA were airborne and heading for four major PT-boat bases along the North Vietnamese coast. The area of coverage ranged from a small base at Quang Khe 50 miles north of the demarcation line between North and South Vietnam, to the large base at Hon Gai in the north.

On August 5, 1964, Stockdale led a flight of sixteen aircraft from the TICONDEROGA on the Vinh petroleum storage complex at 1:30 p.m. in response to the presidential directive to destroy gunboats and supporting facilities in North Vietnam which the President indicated were used in the attack on the MADDOX. The results saw 90 percent of the storage facility at Vinh go up in flames. Meanwhile, other coordinated attacks were made by aircraft from the CONSTELLATION on nearby Ben Thuy Naval Base, Quang Khe, Hon Me Island and Hon Gai’s inner harbor. Skyraiders, Skyhawks and F8s bombed and rocketed the four areas, destroying or damaging an estimated twenty-five PT-boats, more than half of the North Vietnamese force.

Air wing command was usually placed in the hands of an individual who had completed a tour as squadron commander of an attack or fighter unit. The CAG was typically a better than average pilot with a solid record of performance, and more than likely he was a pretty fair politician. By another definition, he’d survived in a profession unforgiving of error.

On his second Vietnam tour, CDR James B. Stockdale was the commander of Air Wing 16 onboard the USS ORISKANY. He had led the successful strike off the TICONDEROGA against the petroleum storage facility at Vinh on August 4, 1964. On one mission, he had the canopy blown off his aircraft and had to ditch in the Gulf of Tonkin where he was rescued. Then on September 9, 1965 flying an A4E Skyhawk, he led another strike mission over North Vietnam. A major strike had been scheduled against the Thanh Hoa (“Dragon Jaw”) bridge, and the weather was so critical there was a question whether to launch. Finally the decision was to launch. Halfway through, weather reconnaissance reported the weather in the target area was zero, and Stockdale had no choice but to send the aircraft on secondary targets.

Stockdale and his wingman, CDR Wynn Foster, circled the Gulf of Tonkin while another strike element departed to look for a SAM site at their secondary target. Had anything been found, Wynn and Stockdale were to join them. After fifteen minutes or so, the other group came up empty. The group made the decision to hit a secondary target, a railroad facility near the city of Thanh Hoa.

CDR Stockdale’s aircraft was hit by flak and he ejected, landing in a village. His wingman saw the parachute go down, but could not see what was happening to Stockdale on the ground. On a low pass, Foster saw that the villagers were brutally beating Stockdale. There was nothing he could do. The village was an unauthorized target. Throughout the rest of the war, Foster carried the guilt of being unable to do something to help CDR Stockdale.

James Stockdale was captured by the Vietnamese and taken to Hanoi, where he spent the next seven and one-half years as a prisoner of war. He had briefed his pilots during the period he was CAG on the ORISKANY that the Code of Conduct would apply to anyone captured. There had been some dispute about the validity of the Code in Vietnam, an undeclared war. American POWs who had flown with Stockdale had no doubt as to what was expected of them as prisoners. The knowledge, however, was a two-edged sword–on one hand, the captives were glad to understand the guidelines. On the other, when they “broke” (which inevitably they did), immense guilt and shame ensued. Eventually, as they communicated with one another, everyone understood that they had only to do their best.

It was not possible to resist utterly and survive. A few who cooperated with the enemy “above and beyond” what was considered appropriate, received special treatment from their guards in return. These men were despised by other POWs who were doing their best to adhere to the Code of Conduct. Upon his return, Jim Stockdale accused two POWs of mutiny. Official charges were never brought against these men, or any others similarly accused.

During his captivity, Stockdale was considered to be a troublemaker by the Vietnamese. As a senior officer, Stockdale developed a policy of behavior for the POWs called “BACK US.” The policy provided guidance on such things as propaganda broadcasts, bowing to guards, and unity, thwarting the “obedience” the Vietnamese tried to extract from the American POWs. The POWs were shuffled from one camp to another, many times based on “unsatisfactory” behavior; many were held long periods in solitary confinement; many were tortured in “interrogation” sessions.

During his captivity, Stockdale was considered to be a troublemaker by the Vietnamese. As a senior officer, Stockdale developed a policy of behavior for the POWs called “BACK US.” The policy provided guidance on such things as propaganda broadcasts, bowing to guards, and unity, thwarting the “obedience” the Vietnamese tried to extract from the American POWs. The POWs were shuffled from one camp to another, many times based on “unsatisfactory” behavior; many were held long periods in solitary confinement; many were tortured in “interrogation” sessions.

In early 1969, one of the POWs became ill and was in great pain at a camp known as Alcatraz, located some ten blocks from the famed Hoa Lo (Hanoi Hilton). The man was receiving no medical care, and fellow prisoners put the pressure on. What ensued might be called a prison riot. The efforts did bring a doctor to the ill POW’s cell, although the doctor did nothing to ease his pain. The next morning, Stockdale organized a forty-eight hour fast to demand medical attention for the ailing officer. The next evening each prisoner was interrogated and on the morning of January 27, Stockdale was taken away to another prison center. Finally, on February 12, 1973, Jim Stockdale was released from prisoner of war camps and sent home.

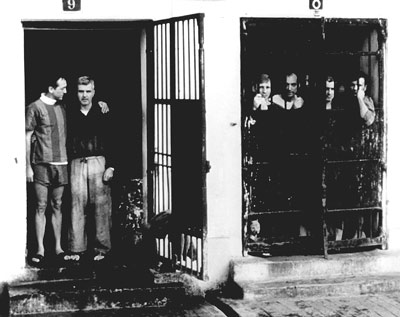

(Stockdale is second man on the left.)

In all, 591 Americans were released. Since the war ended, nearly 10,000 reports relating to Americans missing, prisoner or unaccounted for in Southeast Asia have been received by the U.S. Government. Many authorities who have examined this largely classified information are convinced that hundreds of Americans are still held captive. These reports are the source of serious distress to many returned American prisoners. They had a code that no one could honorably return unless all of the prisoners returned. Not only that code of honor, but the honor of our country is at stake as long as even one man remains unjustly held. It’s time we brought our men home.

Retired Navy VADM James B. Stockdale, Medal of Honor recipient, former Viet Nam prisoner of war (POW), naval aviator and test pilot, academic, and American hero died July 5, 2005, at his home in Coronado, Calif. He was 81 years old and had been battling Alzheimer’s disease.

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 8

SERVICE:

U.S. Marine Corps 1942-1945

U.S. Army Reserve 1946-1949

Iowa Air National Guard 1949-1951

U.S. Air Force 1951-1977

World War II 1942-1945

Cold War 1945-1977

Korean War 1953

Vietnam War 1967-1973 (POW)

Bud Day was born on February 24, 1925, in Sioux City, Iowa. He enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps on December 10, 1942, and spent 30 months in the South Pacific during World War II before receiving an honorable discharge on November 24, 1945.

After the war, Day joined the U.S. Army Reserve on December 11, 1946, and served until December 10, 1949. He was appointed a 2d Lt in the Iowa Air National Guard on May 17, 1950, and went on active duty in the U.S. Air Force on March 15, 1951.

Lt Day completed pilot training and was awarded his pilot wings at Webb AFB, Texas, in September 1952, and completed All-Weather Interceptor School and Gunnery School in December 1952. He served as an F-84 Thunder jet pilot with the 559th Strategic Fighter Squadron of the 12th Strategic Fighter Wing at Bergstrom AFB, Texas, from February 1953 to August 1955, with deployments to Omisawa, Japan, during this time in support of the Korean War.

His next assignment was as an F-84 and F-100 Super Sabre pilot with the 55th Fighter Bomber Squadron of the 20th Fighter Bomber Wing and later on the wing staff at RAF Wethersfield, England, from August 1955 to June 1959, followed by service as an Assistant Professor of Aerospace Science at the Air Force ROTC detachment at St. Louis University in St. Louis, Missouri, from June 1959 to August 1963. During his service in England, he became the first person ever to live through a no-chute bailout from a jet fighter.

CPT Day attended Armed Forces Staff College for Counterinsurgency Indoctrination training at Norfolk, Virginia, from August 1963 to January 1964, and then served as an Air Force Advisor to the New York Air National Guard at Niagara Falls Municipal Airport, New York, from January 1964 to April 1967.

MAJ Day then deployed to Southeast Asia, serving first as an F-100 Assistant Operations Officer at Tuy Hoa AB, South Vietnam, before organizing and serving as the first commander of the Misty Super FACs at Phu Cat AB, South Vietnam, from June 1967 until he was forced to eject over North Vietnam and was taken as a Prisoner of War on August 26, 1967. He managed to escape from his captors and make it into South Vietnam before being recaptured and taken to Hanoi. After spending 2,028 days in captivity, COL Day was released during Operation Homecoming on March 14, 1973. He was briefly hospitalized to recover from his injuries at March AFB, California, and then received an Air Force Institute of Technology assignment to complete his PhD in Political Science at Arizona State University from August 1973 to July 1974.

His final assignment was as an F-4 Phantom II pilot and Vice Commander of the 33rd Tactical Fighter Wing at Eglin AFB, Florida, from September 1974 until his retirement from the Air Force on December 9, 1977. MISTY 1, Col Bud Day, died on July 27, 2013, and was buried at Barrancas National Cemetery at NAS Pensacola, Florida.

His Medal of Honor Citation reads:

On 26 August 1967, Col. Day was forced to eject from his aircraft over North Vietnam when it was hit by ground fire. His right arm was broken in 3 places, and his left knee was badly sprained. He was immediately captured by hostile forces and taken to a prison camp where he was interrogated and severely tortured. After causing the guards to relax their vigilance, Col. Day escaped into the jungle and began the trek toward South Vietnam. Despite injuries inflicted by fragments of a bomb or rocket, he continued southward surviving only on a few berries and uncooked frogs. He successfully evaded enemy patrols and reached the Ben Hai River, where he encountered U.S. artillery barrages. With the aid of a bamboo log float, Col. Day swam across the river and entered the demilitarized zone. Due to delirium, he lost his sense of direction and wandered aimlessly for several days. After several unsuccessful attempts to signal U.S. aircraft, he was ambushed and recaptured by the Viet Cong, sustaining gunshot wounds to his left hand and thigh. He was returned to the prison from which he had escaped and later was moved to Hanoi after giving his captors false information to questions put before him. Physically, Col. Day was totally debilitated and unable to perform even the simplest task for himself. Despite his many injuries, he continued to offer maximum resistance. His personal bravery in the face of deadly enemy pressure was significant in saving the lives of fellow aviators who were still flying against the enemy. Col. Day’s conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Air Force and reflect great credit upon himself and the U.S. Armed Forces.

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 7

Former U.S. senator Adm. Jeremiah Denton, who died at age 89 on 28 March 2014, was interred at Arlington National Cemetery in a service highlighted by the reading of a letter from George H.W. Bush, the appearance and testimonies of fellow Vietnam POWS and attendance by two U.S. senators and a member of the House who shared time with him at the “Hanoi Hilton,” the infamous torture chamber that Denton defied. He wrote a classic – “When Hell Was in Session” that included accounts of his later service in the U.S. Senate with President Ronald Reagan.

Former U.S. senator Adm. Jeremiah Denton, who died at age 89 on 28 March 2014, was interred at Arlington National Cemetery in a service highlighted by the reading of a letter from George H.W. Bush, the appearance and testimonies of fellow Vietnam POWS and attendance by two U.S. senators and a member of the House who shared time with him at the “Hanoi Hilton,” the infamous torture chamber that Denton defied. He wrote a classic – “When Hell Was in Session” that included accounts of his later service in the U.S. Senate with President Ronald Reagan.

Among those in attendance were Sens. Richard Shelby, R-Ala., and Jeff Sessions, R-Ala.; Rep. Sam Johnson, R-Texas, a fellow POW; and Capt. Red McDaniel, author of “Scars and Stripes” and also a fellow POW at the Hanoi Hilton.

Bush’s written tribute said: “We do have heroes … Adm. Jeremiah Denton … was a hero in the truest sense of the word.”

Denton was laid to rest not far from the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

He survived nearly eight years in captivity in Vietnam, including time in the infamous “Hanoi Hilton” after his Navy A-6A Intruder jet was shot down on a bombing mission in 1965.

Four of those years in incarceration were in solitary confinement where he endured starvation and torture in horrendous conditions.

He tells the story in his book “When Hell Was in Session.”

In 1980, he became the first Republican elected to the U.S. Senate from Alabama since Reconstruction. He was a strong supporter of the traditional family and chaired a subcommittee on internal security and terrorism that focused on communist threats.

Reagan, who relied on him for advice on foreign policy, lauded Denton in his 1982 State of the Union address.

“We don’t have to turn to our history books for heroes. They are all around us. One who sits among you here tonight epitomized that heroism at the end of the longest imprisonment ever inflicted on men of our armed forces,” Reagan said.

“Who will ever forget that night when we waited for the television to bring us the scene of that first plane landing at Clark Field in the Philippines – bringing our POWs home? The plane door opened and Jeremiah Denton came slowly down the ramp. He caught sight of our flag, saluted, and said, ‘God Bless America,’ then thanked us for bringing him home.”

He died in Virginia Beach, Virginia, at Sentara Hospice House, said his son, Jeremiah A. Denton 3rd. He is also survived by his second wife, Mary Belle Bordone, four other sons, William, Donald, James and Michael; two daughters, Madeleine Doak and Mary Beth Hutton; a brother, Leo; 14 grandchildren and six great grandchildren.

In “When Hell Was in Session,” Jeremiah Denton, the senior American officer to serve as a Vietnam POW, tells the amazing story of nearly eight years of abuse, neglect and torture. This historic book takes readers behind the closed doors of the Vietnamese prison to see how the men fought back against all odds and against all kinds of evil. It’s available today at a special price.

Denton achieved widespread recognition during his imprisonment. In an internationally televised press conference in 1966 staged by the North Vietnamese for propaganda purposes, he answered the interviewer’s questions while simultaneously blinking, in Morse code, the message “T-O-R-T-U-R-E.” The message confirmed to the U.S. for the first time that U.S. POWs were being tortured in captivity.

Further, he shocked his captors when answering questions about what he thought of U.S. actions.

“I don’t know what is going on in the war now because the only sources I have access to are North Vietnam radio, magazine and newspapers, but whatever the position of my government is, I agree with it, I support it, and I will support it as long as I live.”

When he returned on Feb. 12, 1973, he landed at Clark Air Force Base, walked to a waiting microphone and said: “We are honored to have the opportunity to serve our country under difficult circumstances. We are profoundly grateful to our commander-in-chief and to our nation for this day. God bless America.”

He explained how he survived when so many didn’t. “My principal battle with the North Vietnamese was a moral one, and prayer was my prime source of strength,” he said.

The Navy Cross was among the recognitions for his service.

Reagan showed profound respect for Denton.

“Jerry and I came into office in the same year, 1981, and for the last four-and-a-half years, he’s been a pillar of support for our efforts to keep America strong and free and true,” Reagan said. “He’s been rated the most conservative senator by the National Journal. That’s my kind of senator,” Reagan said. “His voting record has been rated 100 percent by the American Conservative Union, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the Conservatives Against Liberal Legislation – I like the name of that one – The National Alliance of Senior Citizens, the Christian Voters Victory Fund, and some others.”

Reagan also noted a poll by the magazine Conservative Digest ranked Denton as the second most admired senator. “Now, knowing Jerry, he’s probably wondering where he slipped up,” Reagan quipped.

His humanitarian work, however, began in his Senate years with the Denton Program, which allowed the U.S. military to haul humanitarian aid on a space-available basis at no cost to the donor. The program now is administered by the U.S. Agency for International Development, the State Department and Defense Department.

His foundation summed up his life in a statement last year.

“It is his belief in, and knowing of God, that is his pillar. This is the central guiding force in his life not only today, but throughout his life,” the foundation said. “Especially in the small, dark jail cell as a POW … for over seven years during the Vietnam war.”

Family man

Born in Mobile, Alabama, on July 15, 1924, his mother and father divorced in 1938. That experience, he said, was one reason why he became such a strong advocate for the nuclear family. ”

He graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1946 and earned a master’s degree in international affairs from George Washington University in 1964.

He married his first wife, the former Kathryn Jane Maury of Mobile, in June 1946, and had seven children with her.

In 2007, they moved from near Mobile to Williamsburg, Virginia, to be closer to some of their children. Mrs. Denton died Nov. 22, 2007, at 81.

His book, “When Hell was in Session,” begins with the shock he experienced upon his return to the United States in 1973 to find his beloved nation had drastically changed since his capture in 1965.

“I saw the appearance of X-rated movies, adult magazines, massage parlors, the proliferation of drugs, promiscuity, pre-marital sex, and unwed mothers.”

That scenario, he wrote, was coupled with “the tumultuous post-war Vietnam political events, starting with Congress forfeiting our military victory, thus betraying our victorious American and allied servicemen and women, who had won the war at great cost of blood and sacrifice.”

Reagan’s ‘amazing lift’

Denton wrote that when he began his Senate service he was not optimistic, recognizing he was “joining a Congress that had voted to sell out the freedom-loving people of South Vietnam, a Congress that voted, in spite of our military victory, to abandon Southeast Asia to the Communists.”

But he received an “an amazing lift” to his “morale and hopes” when President Reagan took him aside to tell him of his great admiration and respect and to invite him to call on him personally if he had anything he believed the president needed to hear.

Denton took up Reagan on his offer, hatching a plan to thwart the rise of communism in Latin American led by Nicaraguan leader Daniel Ortega, who was riding a wave of popularity in U.S. media and academia even as he worked to spread revolution to El Salvador.

Denton secured permission from the State Department to divert a scheduled trip to El Salvador and, instead, fly to Nicaragua to put Ortega’s boasts of freedom and democracy to the test.

Denton described his ambitious venture as a nervy game of single-hand poker with Nicaragua’s leadership. With confidence borne from dealing with “similar people” during his eight years of communist captivity, he held his own, warning Nicaragua’s startled regime, face to face, that any further acts of aggression would be met with a “reaction from the United States under President Reagan different from what you found under President Johnson in North Vietnam.”

Later, Denton found himself in the Oval Office with Reagan, proposing a comprehensive strategy for confronting communism in Latin America that the president accepted and successfully implemented.

‘Misinformation campaign’

Denton observed that since Reagan’s time, “things have not gone as well.”

“One malady continues to worsen: the on-going influence exerted by the misinformation campaign waged by the liberal media/academic community continues to confuse the citizenry,” he wrote.

In an interview in 2009, Denton said one of the problems he saw at the time was the disdain for “ideology” by many of the nation’s most influential leaders and lawmakers. “They are acting like ideology shouldn’t be the point for any discussion of policy,” he said, with energy in his voice belying his 85 years. “[Balderdash!] Ideology is the basis for which you evaluate any policy.”

The most basic principle that distinguishes America as a nation, he said, is the Declaration of Independence’s assertion that all men are created equal and endowed by their creator with inalienable rights. “Nobody is interpreting rights now in terms of the Creator,” he said. “He endowed the rights.”

President Obama, Denton contended, was usurping the rights of God, “as did Hitler and Stalin and the emperors of Rome.”

“They all had gods – but when they didn’t have good enough gods to constitute a culture, they went to hell,” Denton told WND. “And we are too, if we continue to believe that man, all of us individually, or our government, can determine what the rights are and set up everything else to match that. We’re done.”

Denton said he believed the U.S. is in its worst security position since World War II, when Hitler was sweeping across Europe.

He explained that in the aftermath of that war, the U.S. didn’t have to worry as much about its conventional weapons and forces because of its nuclear might and the doctrine of “mutually assured destruction” with the Soviet Union.

But now, he said, with a decreasing percentage of America’s GDP devoted to defense – coupled with China’s and Russia’s buildup of conventional forces – America’s security is at risk.

“If Russia were to take over first Georgia, then Ukraine – and maybe China moves into India – we couldn’t go there with a conventional force and stop that, and we wouldn’t have the guts to use nuclear, for good reason,” he said. Denton said that while the military leaders with whom he spoke agreed with his analysis, President Obama didn’t recognize the problem. “We don’t really have the proper national intelligence the way we used to have,” he said. “We had people like Clare Boothe Luce and brilliant people from many different fields come in, but we don’t do that anymore. It’s done on a haphazard basis.”

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 6

Who was Colonel Nick Rowe? He was first and foremost a Special Forces Officer. He was a West Point graduate. He was a former POW, having suffered for five years at the hands of his North Vietnamese captors before escaping and making his way back to US forces on his own. He was a teacher in that he founded and taught the U.S. Army Special Forces Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) Program which trains military of all branches how to survive if they are separated from their forces, how to evade the enemy and make their way back to friendly forces, how to resist the enemy if captured, and how to plan an escape. He was a devout Christian. He was a real live hero of our times who became a living legend in the Special Forces community until his untimely assassination by guerilla insurgents in the Philippines.

The VIETNAM YEARS

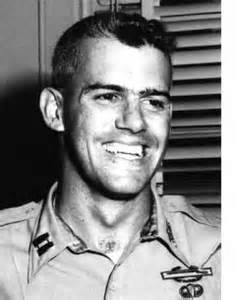

1st Lieutenant “Nick” Rowe

On October 29, 1963, Capt. “Rocky” Versace, 1Lt. “Nick” Rowe, and Sgt. Daniel Pitzer were accompanying a Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) company on an operation along a canal. The team left the camp at Tan Phu for the village of Le Coeur to roust a small enemy unit that was establishing a command post there. When they reached the village, they found the enemy gone, and pursued them, falling into an ambush at about 1000 hours. The fighting continued until 1800 hours, when reinforcements were sent in to relieve the company. During the fight, Versace, Pitzer and Rowe were all captured.

For 62 months, Rowe battled dysentery, beriberi, fungal diseases, and grueling psychological and physical torment. Each day he faced the undermining realization that he might be executed, or worse, kept alive, but never released. His home was a wooden cage, three feet by four feet by six feet in dimension. His bed was a sleeping mat. In spite of all this, Rowe was a survivor. From the start of his capture, he began looking for ways to resist his captors while he could make plans for his escape. Since he was the S2 or Intelligence Officer for his unit, he had access to all sorts of classified and sensitive information including camp defenses, mine field locations, names of friendlies and unit strengths and locations. All information the Viet Cong would love to know.

Rowe concocted a cover story that he was a “draftee” engineer who had the mundane job of building schools and other civil affairs projects. A 1960 graduate of West Point, Rowe had left his ring at home with his parents when he came to Vietnam. Nick instead made up the story that he went to a small liberal college and really didn’t know much about the military. The Viet Cong unsure whether to believe Rowe used torture to see if he would break and change his story. As a last resort his interrogators gave him some basic engineering problems which they felt would either validate Rowe’s story or prove that he was lying. Fortunately, as engineering courses were mandatory at West Point, Rowe was able to fool his captors.

Rowe’s cover story was eventually broken but not through any fault of his own. All his efforts were destroyed when a peace seeking group of war protesters came to North Vietnam. As part of their visit to North Vietnam, the protesters had asked to see some of the American POW’s so they could tell the American people that they were being treated fairly by the North Vietnamese government. Rowe’s name was on their list that they gave their hosts along with the information that he was the intelligence officer for the Special Forces Advisor Unit.

Rowe’s captors were furious that Rowe had fooled them all this time. Even worse was they knew that the valuable information he had at the time of his capture was dated and virtually worthless to them now. Rowe’s captors beat him for hours then stripped him and staked him out naked in a swamp. Now if you have ever had a mosquito bite you, you know how much it hurts and itches. That night Rowe’s body was covered with a blanket of mosquitoes that feasted on him for two days. Despite his captors best efforts to torture him, Rowe still would not break to their will or give them the old dated information.

Rowe made several escape attempts, once with another injured POW. They were being pursued by the Viet Cong when the other POW faced the realization that he could not go on and that he was slowing Rowe down and increasing the chance of both men being captured again. He urged Rowe to go on without him. Rowe began doing so until he heard the Viet Cong capture his friend. They began yelling that unless he surrendered to them, they would kill his friend. Although Rowe could have escaped he surrendered to save his friend.

Rowe was scheduled to be executed in late December 1968. His captors had had enough of him – his refusal to accept the communist ideology and his continued escape attempts. On Dec. 31, 1968, while away from the camp in the U Minh forest, Rowe took advantage of a sudden flight of American helicopters. He struck down his guards, and ran into a clearing where the helicopters noticed him and rescued him, still clad in black prisoner pajamas. Among his surprises when he returned to civilization was that he had been promoted to Major during his five years of captivity.

Rowe eating his first meal in the hospital after his escape

Rowe eating his first meal in the hospital after his escape

In 1971 Nick published Five Years to Freedom, in which he recounted his ordeal as a Viet Cong prisoner, his eventual escape, and his return home. The book was the result of the diary he wrote while prisoner, writing it in German, Spanish, Chinese, and his own special code in order to deceive his captors. He also wrote Southeast Asia Survival Journal for the United States Department of the Air Force, published n 1971. Upon his return home to McAllen, Texas, he was presented with lifetime memberships in the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars.

In 1974 he made the decision to leave the service. He continue to write co-authoring The Washington Connection with Robin Moore, which was published by Conder Press in 1977, and in the same year Little, Brown and Company published his first novel, The Judas Squad.

Fort Bragg and The Philippines

LTC Rowe

The United States Army Special Forces School at Fort Bragg, North Carolina recognized the need for creating the SERE Program. When they started to look for an Officer to design the course and implement it into operation, Nick was everyone’s first choice. He returned to the Army and Special Forces as a lieutenant colonel in 1981 and given the mission to develop and run such a program. His efforts resulted in a program that would leave behind a tremendous legacy at Fort Bragg: a course based on his prisoner-of-war experience. Called SERE – Survival Evasion Resistance Escape – the course today is considered by many as the most important advanced training in the special operations field. Taught at the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School, SERE trains soldiers to avoid capture, but if caught, to survive and return home with honor. Much of the SERE course is conducted at the Rowe compound.

In 1985, Rowe left instructor duty to take command of a Battalion with the 5th Special Forces Group.

In 1987, Rowe was assigned to the Philippines, where he was given the mission of chief of the army division of the Joint U.S. Military Advisory Group (JUSMAG) providing counter-insurgency training for the Philippine military. In this capacity, he worked closely with the CIA, and was involved in its nearly decade-old program to penetrate the communist New Peoples’ Army (NPA) and its parent communist party in conjunction with Philippine’s own intelligence organizations. Nick proved to be the right man for the job quickly earning the respect of the Philippine government and the hatred of the communist guerrillas who hoped to disrupt President Aquino’s democratic Philippine government.

By February, 1989, Colonel Rowe had developed his own intelligence information which indicated that the communist were planning a major terrorist act. As a result of the intelligence and his analysis of the situation in the Philippines, Rowe wrote Washington warning that a high-profile figure was about to be hit and that he, himself, was No.2 or No.3 on the terrorist list.

Nick knew that his death would be a real propaganda victory for the communists. The communist guerillas had put a price on his head hoping to kill him and embarrass the Philippine government. In mid-April, 1989, Nick sent his green beret and bible home to his wife for safekeeping along with a letter informing her that he expected the NPA communists would be intensifying their actions with a planned major terrorist acts against U.S. military advisors their most likely action. Nick assured his wife that he was taking every precaution.

On April 21, 1989, Nick was returning to the US Embassy in an armored limousine when hooded members of the communist New Peoples’ Army (NPA) attacked his vehicle with automatic weapons. Under normal circumstances these weapons alone would not have been a threat to the occupants of the vehicle. However, “Murphy’s Law” of “Whatever can go wrong will go wrong” was in full force. The vehicle’s air conditioning had broken down earlier making the inside of the vehicle almost unbearable in the Philippine heat. To compensate but still provide safety, the driver had opened the small window vent to allow fresh air to circulate into the car. Several rounds found their way through the open vent killing Nick instantly.

The US State Department called it a “Random Terrorist Act”, however evidence suggests that Nick’s Vietnam experience was not coincidental to his selection as a target. In June of 1989, from an NPA stronghold in the hills of Sorsogon, a province in Southern Luzon’s Bicol region, senior cadre Celso Minguez told the Far Eastern Economic Review magazine that the communist underground wished to send “a message to the American people” by killing a Vietnam veteran.

Minguez, a founder of the communist insurgency in Bicol and participant in the abortive 1986 peace talks with President Corazon Aquino’s government told the REVIEW.

We want to let them know that their government is making the Philippines another Vietnam.

In May 1989, U.S. Veteran News and Report reported that according to a source who had served under Col. Rowe, the Vietnamese communist also wanted him dead and very likely collaborated with the Philippine insurgents to achieve that goal.

The source who wished to remain anonymous said that prior to Col. Rowe being assigned to the Philippines in 1987, at one point in Greece while he was on assignment, Delta Force, the U.S. anti-terrorist organization, moved in, secured the area and relocated him. They had received reports that Vietnamese communist agents were planning an action against him:

He was a target when he went over there because of his dealings with the North Vietnamese and his time as a prisoner.

Robert Mountel, a retired Special Forces colonel and former commander of the 5th Special Forces Group, subsequently explained, confirming what the other source had said:

They had him on their list.

There are several unanswered questions. Among them: How did the Guerilla’s know where Colonel Rowe would be? Only the Embassy allegedly knew the route that Colonel Rowe was to take that day. Colonel Rowe consistently varied his schedule and routes of travel. Why is it that he was ordered NOT to be armed, though his name was known to be on the communist guerillas’ “hit” List? And why did President Aquino, who Colonel Rowe was in the Philippines to help, later grant freedom to all of his killers?