Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 20

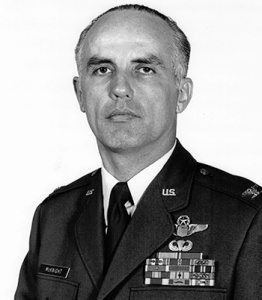

MCKNIGHT, GEORGE GRISBY

MCKNIGHT, GEORGE GRISBY

Branch/Rank: UNITED STATES AIR FORCE/O3

Unit: 602 ACS

Home City of Record: ALBANY OR

Date of Loss: 06-November-65

Country of Loss: NORTH VIETNAM

Aircraft/Vehicle/Ground: A1E

Missions: 50+MISSION

Colonel O-6, U.S. Air Force

U.S. Air Force Reserve 1955-1956

U.S. Air Force 1956-1986

Cold War 1955-1986

Vietnam War 1964-1973 (POW)

George McKnight was born in 1933 in Albany, Oregon. He was commissioned a 2d Lt in the U.S. Air Force through the Air Force ROTC program on July 15, 1955, and went on active duty beginning January 23, 1956. Lt McKnight completed pilot training and was awarded his pilot wings at Laredo AFB, Texas, in February 1957, and then completed F-100 Super Sabre Combat Crew Training in September 1957.

His first assignment was as an F-100 pilot with the 35th Fighter-Bomber Squadron at Itazuke AB, Japan, from October 1957 to June 1961 followed by service as an F-100 pilot with the 428th and then the 430th Tactical Fighter Squadron at Cannon AFB, New Mexico, from July 1961 to January 1965.

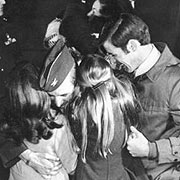

During this time, he deployed to Southeast Asia and flew combat missions from Takhli Royal Thai AFB, Thailand, from November to December 1964. Capt McKnight next completed A-1 Skyraider training at Eglin AFB, Florida, and then served as an A-1 pilot with the 602nd Fighter Squadron at Bien Hoa AB, South Vietnam, from July 1965 until he was forced to bail out over North Vietnam and was taken as a Prisoner of War on November 6, 1965. McKnight, a captain at the time, was taken as a POW in November 1965. He was an A-1 Skyraider pilot, assigned to the 602nd Fighter Squadron at Bien Hoa Air Base, South Vietnam. After spending 2,656 days in captivity, Col McKnight was released during Operation Homecoming on February 12, 1973. He was briefly hospitalized to recover from his injuries at Travis AFB, California, and then attended the Air War College at Maxwell AFB, Alabama, from August 1973 to July 1974.

Speaking about his POW experience, COL McKnight states:

“I was a POW for 7 years, 3 months, 2 days, 4 hours and 3 minutes,” he said of the confinement that lasted until the end of the war. He and 10 others, including U.S. Sen. John McCain, had a name for their prison and for themselves. “We called it Alcatraz Prison and ourselves the Alcatraz 11. We were all in solitary confinement.”

McKnight said he never saw his fellow American prisoners until they were released, with the exception of one escape attempt. Prisoners were kept in individual cells and communicated with one another by tapping on the walls — a code they learned in case they were captured.

“It was exactly like text messaging,” he said with a laugh. “So we invented it. We want our money back.”

When he returned to the Air Force War College in Montgomery, Ala., he met a woman in the Nurse Corps. He and Suzanne married, and 34 years later are “living happily ever after.”

To McKnight, Veterans Day is a time to especially honor the country’s young service men and women.

“It’s amazing they can get those men and women without the threat of the draft,” he said, his voice catching with emotion. “Those guys today are volunteers. So they are very special soldiers.”

His next assignment was to flight retraining and F-4 Phantom II Combat Crew Training before serving as Special Assistant to the Deputy Chief of Operations for the 463rd Tactical Fighter Squadron at RAF Lakenheath, England, from March 1975 to April 1976.

COL McKnight then served as Deputy Commander for Operations of the 32nd Tactical Fighter Squadron at Camp New Amsterdam in the Netherlands from May 1976 to March 1978, followed by studies at the Defense Language Institute and then service as Defense Air Attaché to the Democratic Republic of the Congo from October 1978 to May 1982. His final assignment was as Commander in Chief of the U.S. Air Force/Canadian Forces Officer Exchange Program in Ottawa City, Canada, from November 1982 until his retirement from the Air Force on March 1, 1986.

His Air Force Cross Citation reads:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Section 8742, Title 10, United States Code, awards the Air Force Cross to Lieutenant Colonel George G. McKnight for extraordinary heroism in military operations against an opposing armed force while a Prisoner of War in North Vietnam on 12 October 1967. On that date, he executed an escape from a solitary confinement cell by removing the door bolt brackets from his door. Colonel McKnight knew the outcome of his escape attempt could be severe reprisal or loss of his life. He succeeded in making it through a section of housing, then to the Red River and swam down river all night. The next morning he was recaptured, severely beaten, and put into solitary confinement for two and a half years. Through his extraordinary heroism and aggressiveness in the face of the enemy, Colonel McKnight reflected the highest credit upon himself and the United States Air Force.

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 17

Name: Samuel Robert Johnson

Name: Samuel Robert Johnson

Rank/Branch: O4/United States Air Force

Unit: 433rd TFS

Date of Birth: 11 October 1930

Home City of Record: Dallas TX

Date of Loss: 16 April 1966

Country of Loss: North Vietnam

Status (in 1973): Returnee

Aircraft/Vehicle/Ground: F4C

Missions: 25

NOTE: Flew 62 missions in Korea in F-86’s

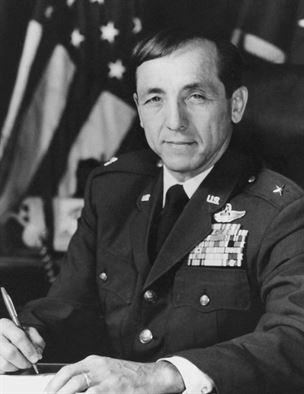

Samuel Robert “Sam” Johnson (born October 11, 1930) is a retired career U.S. Air Force officer and fighter pilot and an American politician. He currently is a Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives from the 3rd District of Texas. The district includes much of Collin County, as well as Plano, where he lives.

Johnson grew up in Dallas and graduated from Woodrow Wilson High School. Johnson graduated from Southern Methodist University in his hometown in 1951, with a degree in business administration. While at SMU, Johnson joined the Delta Chi social fraternity as well as the Alpha Kappa Psi business fraternity. He served a 29-year career in the United States Air Force, where he served as director of the Air Force Fighter Weapons School and flew the F-100 Super Sabre with the Air Force Thunderbirds precision flying demonstration team. He commanded the 31st Tactical Fighter Wing at Homestead AFB, Florida and an air division at Holloman AFB, New Mexico, retiring as a Colonel.

He is a veteran of both the Korean and Vietnam Wars as a fighter pilot. During the Korean War, he flew 62 combat missions in the F-86 Sabre. During the Vietnam War, Johnson flew the F-4 Phantom II.

In 1966, while flying his 25th combat mission in Vietnam, he was shot down over North Vietnam. He was a prisoner of war for seven years, including 42 months in solitary confinement. During this period, he was repeatedly tortured.

Johnson was part of a group of 12 prisoners known as the Alcatraz Gang, a group of prisoners separated from other captives for their resistance to their captors. They were held in “Alcatraz”, a special facility about one mile away from the Hỏa Lò Prison, notably nicknamed the “Hanoi Hilton”. Johnson, like the others, was kept in solitary confinement, locked nightly in irons in a 3-by-9-foot cell with the light on around the clock. Johnson recounted the details of his POW experience in his autobiography, Captive Warriors(available through amazon).

Mr. Johnson states “The nearly seven years that I spent in Hanoi but most especially the more than two years in a camp called Alcatraz engendered a close-knit bond between me and some great Americans. I count these men as true friends and their courage and ideals have brought home vividly to me what America is all about. I can only emphasize that the freedoms that most Americans take for granted are in fact, real and must be preserved. I have returned to a great nation and our sacrifices have been well worth the effort. I pledge to continue to serve and fight to protect the freedoms and ideals that the United States stands for” and he has done so.”

A decorated war hero, Johnson was awarded two Silver Stars, two Legions of Merit, the Distinguished Flying Cross, one Bronze Star with Combat “V” for Valor, two Purple Hearts, four Air Medals, and three Air Force Outstanding Unit Awards. He was also retroactively awarded the Prisoner of War Medal following its establishment in 1985. He walks with a noticeable limp, due to an old war injury.

After his military career, he established a homebuilding business in Plano. He was elected to the Texas House of Representatives in 1984 and was re-elected four times. In 1990, Johnson was inducted into the Woodrow Wilson High School Hall of Fame. In October 2009, the Congressional Medal of Honor Society awarded Johnson the National Patriot Award, the Society’s highest civilian award given to Americans who exemplify patriotism and strive to better the nation.

On May 8, 1991, he was elected to the House in a special election brought about by eight-year incumbent Steve Bartlett’s resignation to become mayor of Dallas. Johnson defeated fellow conservative Republican Thomas Pauken, also of Dallas, 24,004 (52.6 percent) to 21,647 (47.4 percent). Johnson thereafter won a full term in 1992 and has been reelected nine times. The 3rd has been in Republican hands since 1968. The Democrats did not even field a candidate in 1992, 1994, 1998, or 2004.

2004: Johnson ran unopposed by the Democratic Party in his district in the 2004 election. Paul Jenkins, an independent, and James Vessels, a member of the Libertarian Party ran against Johnson. Johnson won overwhelmingly in a highly Republican district. Johnson garnered 86% of the vote (178,099), while Jenkins earned 8% (16,850) and Vessels 6% (13,204).

2006: Johnson ran for re-election in 2006, defeating his opponent Robert Edward Johnson in the Republican primary, 85 to 15 percent. In the general election, Johnson faced Democrat Dan Dodd and Libertarian Christopher J. Claytor. Both Dodd and Claytor are West Point graduates. Dodd served two tours of duty in Vietnam and Claytor served in Operation Southern Watch in Kuwait in 1992. It was only the fourth time that Johnson had faced Democratic opposition. Johnson retained his seat, taking 62.5% of the vote, while Democrat Dodd received 34.9% and Libertarian Claytor received 2.6%. However, this was far less than in years past, when Johnson won by margins of 80 percent or more.

2008: Johnson retained his seat in the House of Representatives by defeating the Democrat Tom Daley and Libertarian nominee Christopher J. Claytor in the 2008 general election. He won with 60 percent of the vote, an unusually low total for such a heavily Republican district.

2010: Johnson won re-election with 66.3% of the vote against Democrat John Lingenfelder (31.3%) and Libertarian Christopher Claytor (2.4%).

2014: Johnson handily won re-nomination to his thirteenth term, twelfth full term, in the U.S. House in the Republican primary held on March 4, 2014. He polled 30,943 votes (80.5 percent); two challengers, Josh Loveless and Harry Pierce, held the remaining combined 19.5 percent of the votes cast.

In the House, Johnson is an ardent conservative. By some views, Johnson had the most conservative record in the House for three consecutive years, opposing pork barrel projects of all kinds, voting for more IRAs and against extending unemployment benefits. The conservative watchdog group Citizens Against Government Waste has consistently rated him as being friendly to taxpayers. Johnson is a signer of Americans for Tax Reform’s Taxpayer Protection Pledge. Johnson is a member of the conservative Republican Study Committee, and joined Dan Burton, Ernest Istook and John Doolittle in re-founding it in 1994 after Newt Gingrich pulled its funding. He alternated as chairman with the other three co-founders from 1994 to 1999, and served as sole chairman from 2000 to 2001.

On the Ways and Means Committee, he was an early advocate and, then, sponsor of the successful repeal in 2000 of the earnings limit for Social Security recipients. He proposed the Good Samaritan Tax Act to permit corporations to take a tax deduction for charitable giving of food. He chairs the Subcommittee on Employer-Employee Relations, where he has encouraged small business owners to expand their pension and benefits for employees. Johnson is a skeptic of calls for increased government regulation related to global warming whenever such government interference would, in his mind, restrict personal liberties or damage economic growth and American competitiveness in the market place. He also opposes calls for government intervention in the name of energy reform if such reform would hamper the market and or place undue burdens on individuals seeking to earn decent wages. He has expressed his belief that the Earth has untapped sources of fuel, and has called for allowing additional drilling for oil in Alaska. Johnson is one of two Vietnam-era POWs still serving in Congress.

Johnson is married to the former Shirley L. Melton, of Dallas. They are parents of three children and ten grandchildren.

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 13

Name: Ronald Edward Storz

Name: Ronald Edward Storz

Branch/Rank: United States Air Force/O3

Date of Birth: 21 October 1933

Home City of Record: SOUTH OZONE PARK NY

Date of Loss: 28 April 1965

Country of Loss: North Vietnam

Status (in 1973): Prisoner of War/Died in Captivity

Category: 1

Aircraft/Vehicle/Ground: O1A

The following is QUOTED directly from THE PASSING OF THE NIGHT, by Brigadier Gen Robinson Risner, Copyright 1973, Ballantine Books. Pages 63 – 71.

“One day they replaced Shumaker with Air Force Captain Ron Storz. I tapped on the wall to him, got his name, and so forth. He said that up until this move, he had been living with Captain Scotty Morgan. “I leaned on the door and broke the lock. Now I am over here alone being punished.” Ron told me he had been shot down in an L 1 9, one of those little planes called grasshoppers. Since he, as a forward air controller, normally worked with Vietnamese ground forces, he would carry a Vietnamese officer in the back seat. His mission was to circle and spot enemy positions or helps the artillery batteries adjust for accuracy. “One afternoon I decided to go up and buzz around by myself. I was just looking the area over, and I circled real close to the Ben Hi River. I knew that was the seventeenth parallel, but I didn’t mean to get over the river. When I did, a Vietnamese gun got me, and tries as I might, I could not keep from crashing on the north side. I thought they were going to kill me when I got out of the airplane. They made me get down on my knees. One of the officers took my gun, cocked it and put it against my head. I figured I was a goner.” He had been in prison for some time and really wanted to talk. I could hear him moving around in the other cell. He hollered out the back vent as Bob before him had done, but I could never understand him. We tapped on the wall, but it was too slow and unsatisfactory.

There were a lot of things we wanted to tell each other. Finally he asked, by tapping, “Have you tried boring a hole through the wall yet?” I told him I had tried several places but could not get through. “Each time I try, I hit a brick after I’ve gone in maybe eight to twelve inches.” I had several partial holes; in fact, the wall looked like a piece of Swiss cheese. “Well, I’ll try, too.” Pretty soon I heard some scraping and grinding. By that afternoon he was through. His hands were blistered, but he had made it. That gave me some incentive to try to go through the other wall. I really went to work, and I punched through there, too. We passed our tools through and let them work in the next room. In a few days, every room was connected up and down the hall.

Once we got the holes bored through, Ron said, “I’m really down in the mouth.” I asked what the matter was. “Well, just the fact that I have nothing. They have taken everything away from me. They took my shoes, my flying suit, and everything I possessed. They even took my glasses. I don’t have a single thing. They took everything.” Ron had indicated to me that he planned to become a minister when he got back to America. Consequently we talked about religion quite a bit, as all of us did. When he said he was depressed because they had taken everything, I told him, “Ron, I don’t think we really have lost everything.” “What do you mean?” “According to the Bible, we are sons of God. Everything out there in the courtyard, all the buildings and the whole shooting match belong to God. Since we are children of God, you might say that all belongs to us, too.” There was a long pause. “Let me think about it, and I’ll call you back.” After a while he called back, “I really feel a lot better. In fact, every time I get to thinking about it, I have to laugh.” “What do you mean?” “I am just loaning it to them.” I will never forget the day he called me and told me, “They’re trying to make me come to attention for the guards and I will not do it. What do you think I ought to do?” “What do they do?” “They cut my legs with a bayonet, trying to make me put my feet together. I am just not going to do it.” I knew he meant it. He was an extremely strong man. I thought about it for a while, then I called back, “Ron, I’m afraid we don’t have the power to combat them by physical force. I believe I would reconsider. Then, if we decide differently, we all should resist simultaneously. With only you resisting while everybody else is doing it means you are bound to lose.” He said, “Okay.” I knew, though, that if I had said, “Ron, hang tough! Refuse to snap to,” he would have done it without batting an eye. He was just that kind of man and he proved it a short time later.

It happened after we had begun to set up a covert communications system throughout the Zoo. By means of the holes in the walls, special hiding places in the latrine and other ways, we could pass a message through the entire camp within two days. I had put out directives establishing committees and worked out a staff. Certain people had been assigned specific jobs. One man was heading up our communications section. We had a committee working on escape. And we kept a current list of all the POWs and their shoot-down date. I then decided to put out a bulletin. It was not too large, but it contained directives, policies and suggestions. Since Ron was next door to me, I dictated it to him, and he wrote it down. Despite the Vietnamese’s denying us our dues as POWs, I still felt that we could outsmart them by using tactics such as these. We had only been at the Zoo around four weeks; given time, I reasoned, we could begin to effect some changes. I could not have been more wrong. One day during this period, a guard came in and made me stand at attention with my back to the wall. In a few minutes the Dog came in with another Vietnamese in a white shirt. The Dog did not say who the civilian was, but he paid him a lot of deference. Using the Dog as an interpreter, the civilian made a statement: “I understand you are also a Korean hero.” I was still standing braced against the Wall. “That is military information and I cannot answer. I can give you only my name, rank, serial number and date of birth.” When he heard the translation, the cords in his neck swelled up and he tamed red in the face. “We know how to handle your kind. We are preparing for you now.” He turned and stomped out. The Dog came back in a little while. He was either so scared or mad that he was still trembling “You have made the gravest mistake in your life. You will really suffer for this.”

With that threat he left. A few days later a guard caught the men two cells above me talking through the hole in the wall to Ron. He also found some written material. Then he went into Ron’s room and caught him by surprise. He took two pieces of written work Ron had prepared; one was a list of all the POW names, the other was one of the bulletins I had put out. To make matters worse, Ron had put my real name on the newssheet instead of my code name, “Cochise.” While still in the cell, one of the guards began reading the two sheets. Ron reached over, snatched one and ate it while holding them off with one hand. Unfortunately he had grabbed the wrong one. He ate the list of names which was not too important, but they kept the list of directives. They also found the hole in the wall. This so excited them that they stepped out in the hall yelling for reinforcements. While they were out, Ron ran over to my wall and beat out an emergency signal to come to our hole in the wall. They searched and found everything. I ate the list of names, but they got the policies. Get rid of anything you don’t want them to find.” I told him to deny everything, and I would do the same.

He just had time enough to stuff the plug back in the hole when they came and took him away. I passed the warning down to the other two rooms and they began to clean house. As fast as possible I began to try and dispose of anything incriminating. The steel rods that we had been using to bore the holes in the walls I put under the floor through the grate. I destroyed lots of paperwork, but the fat was in the fire. A big shakedown was on. One thing I had not destroyed was a sheet of toilet paper that had the Morse code on it. I didn’t think it was any big deal or I would have gotten rid of it. This was one of the pieces of evidence they would use to accuse me of running a communications system. The irony of it was that I actually was relearning the Morse code with the knowledge of my turnkey. He had even written his name on it for me.

They put Ron in another room for three days and nights without anything at all – no food, water, bedding, blankets or mosquito net. They just shoved him in and left him there. He not only got cold, but the mosquitoes chewed on him all night. They took me before the camp commander for interrogation. He had the piece of paper Ron had not been able to destroy and started reading the fourteen items it listed, such as: gather all string, nails and wire; save whatever soap or medicine you get; familiarize yourself with any possible escape routes; become acquainted with the guards, and in general follow the policy that “you can catch more flies with sugar than, with vinegar.” I denied the paper was mine. “Storz has already admitted everything and said you were responsible.” I knew that was a lie.

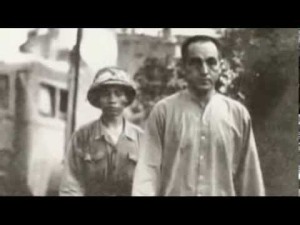

They would have had to kill Ron before he did that. He might admit to his having done it, but he would never say that somebody else had. They, of course, told him the same thing and said that I had admitted everything, and all he had to do was confirm it. After making the usual number of threats, they took me back to a different room at the end of the building. They left me a pencil and paper and told me to write out a confession that I had violated prison rules. “If you do not, you will be severely punished.” The first thing I knew, I heard a tap. It was Ron Storz in the next room. We exchanged what had happened in interrogation. I said, “Remember, I’ll never confess to anything.” “Roger, I won’t either.” He then tapped, “God bless you.” I sent back a GBU. I later heard that Ron was put in Alcatraz, a harsh punishment camp. Though he was an extremely strong man, the torture began to get through to him. The North Vietnamese hated him so that even when they moved out all the other POWs, they left Ron there alone. I later saw one of the postage stamps put out by the North Vietnamese. It was typical North Vietnamese propaganda. On it is a picture of an American POW. He is big and tall. Behind him is a teen-age girl, very small, holding a rifle on him. The American was Ron Storz. When making their report on the POWs in 1973, the North Vietnamese said that Ron Storz “died in captivity.” Ron Storz died as he lived – a brave American fighting man who considered his principles more valuable than his life.”

Ron Storz was beaten unconscious and died on 23 April 1970. His remains were recovered and returned on March 6, 1974.

Have We Forgotton Our Heroes? Chapter 10

Name: Lance Peter Sijan

Rank/Branch: O2/USAF

Date of Birth: 13 April 1942

Home City of Record: Milwaukee WI

Date of Loss: 09 November 1967

Country of Loss: Laos

Loss Coordinates: 171500N 1060800E

Status (In 1973): Killed in Captivity

Category: 1

Acft/Vehicle/Ground: F4C

Lance Peter Sijan, born 13 April 1942, was the son of Sylvester and Jane (Attridge) Sijan of Milwaukee, WI. The following are excerpts from the “Airman” Magazine.

CPT Lance P. Sijan was the first Air Force Academy graduate to receive the Medal of Honor.

THE CODE OF CONDUCT

ARTICLE I – I am an American fighting man. I serve in the forces which guard my country and our way of life. I am prepared to give my life in their defense.

The colonel, recalling the tragic events of almost nine years earlier, had been talking for more than an hour about the heroic ordeal of Capt. Lance P. Sijan, his cellmate in North Vietnam. Reaching the point in his chronology when Sijan, calling out helplessly for his father, was taken away by his captors to die, Col. Bob Craner’s voice broke ever so slightly and tears glistened in his eyes. He agreed to a recess in the interview.

THE CODE OF CONDUCT

ARTICLE II – I will never surrender of my own free will. If in command, I will never surrender my men while they still have the means to resist.

“Okay Mom, you can come back in now!”

The voice, coming from a tape recorder that day in early November 1967, gave immense pleasure to Mr. and Mrs. Sylvester Sijan (pronounced sigh-john), just as it had so many times for more than 25 years. It was especially meaningful now, coming from Da Nang AB, Vietnam. Their son had done his Christmas shopping early and, separated by half a world, was having some mischievous fun with his family.

Sitting in the living room of the comfortable two-story house in Milwaukee, Mrs. Jane Sijan tenderly related the tale of her son’s tape. Across the street, snow was crusted on the park that gently slopes into Lake Michigan. Flames danced in the fireplace as Sylvester Sijan busily prepared to show movies of Lance’s graduation from the Air Force Academy in 1965.

Everywhere was memorabilia of Lance and his brother, Marc, younger by five years, and his sister, Janine, 13 years Lance’s junior. An oil painting bathed in soft neon light on one wall showed Lance in his academy uniform, smiling out into the room.

Along the staircase hung dozens of photos of the Sijans–their children, relatives and friends. Football pictures of Lance and Marc abounded, for football is a tradition with the Sijans. Lance’s Bay View High School team won the city championship in 1959, the first time Bay View had turned the trick since 1936, when Lance’s father played on the team. Family heirlooms, souvenirs from faraway places, and trophies dominated mantels and shelves. The most significant showpiece, however, was enshrined in a glass case. Resplendent with its accompanying baby-blue ribbon dotted with tiny white stars was Capt. Lance Sijan’s Medal of Honor. It had been awarded posthumously.

Jane Sijan–attractive and dark-haired, her Irish heritage smiling through–continued her story of the tape from Vietnam: “Lance made us individually leave the room as he described the Christmas presents he had gotten for us. He’d say, ‘Mom, leave the room,’ and then he’d tell everybody what he had for me. Then he’d yell for me to come back in, and he’d send someone else out.”

Those Christmas presents were not opened that year, nor for several years thereafter. On Nov. 9, 1967, Capt. Lance Sijan was shot down over North Vietnam. For years no one at home knew his fate. The box of Christmas presents was added to his personal effects, and not until his body was returned to Milwaukee some seven years later did his family sort through his belongings.

On March 4, 1976, President Gerald R. Ford awarded the Medal of Honor to Sijan for his “extraordinary heroism and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty at the cost of his life. . . .”

THE CODE OF CONDUCT

ARTICLE III – If am I captured I will continue to resist by all means available. I will make every effort to escape and aid others to escape. I will accept neither parole nor special favors from the enemy.

R&R in Bangkok, Thailand, had been nostalgic for Lance Sijan. He told his family in a tape from the country once known as Siam that his drama teacher at Bay View High School–where Sijan had been president of the Student Government Association and received the Gold Medal Award for outstanding leadership, achievement, and service–would have been impressed. As a sophomore, according to his mother, Lance had competed against seniors for the lead singing role in the school production of “The King and I,” which was set in Siam. Competition raged for six weeks, consuming Lance’s energy and concern.

“One day,” said Jane, “he walked in and said, ‘Well, I’d like to speak to the Queen Mother.’ I knew he had the part.”

There were 21 children in the cast, and Sijan needed one special little princess. He and Marc had always doted over their sister, Janine, even to the point of arguing who would feed her, as an infant, in the middle of the night. Lance asked Janine, then not quite 4 years old, to be his daughter in the play. Occasionally, the family listens to a recording of the play, Lance’s rich voice sing-talking the role of the Siamese king that Yul Brynner made famous.

Sijan flew his first post-R&R mission on Nov. 9, 1967, as the pilot of an F-4 with Col. John W. Armstrong, commander of the 366th Tactical Fighter Squadron, as the backseater. On a bombing pass over North Vietnam near Laos, their aircraft was hit and exploded. Armstrong was never heard from again. Sijan, plummeting to the ground after a low-level bailout, suffered a skull fracture, a mangled right hand with three fingers bent backward to the wrist, and a compound fracture of his left leg, the bone protruding through the lacerated skin.

The ordeal of Lance Sijan–big, strong, tough, handsome, a football player at the Air Force Academy, remembered as a fierce competitor by those who knew him–had begun. He would live in the North Vietnamese jungle with no food and little water for some 45 days. Virtually immobilized, he would propel himself backward on his elbows and buttocks toward what he hoped was freedom. He was alone. He would be joined later by two other Americans, and in short, fading, in-and-out periods of consciousness and lucidity, would tell them his story.

Now, however, there was hope for Lance Sijan. Aircraft circled and darted overhead, part of a gigantic search-and-rescue effort launched to recover him and Armstrong. Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Service histories state that 108 aircraft participated the first two days, and 14 more on the third when no additional contact was made with Sijan, known to those above as “AWOL 1.”

the third when no additional contact was made with Sijan, known to those above as “AWOL 1.”

Contact had been made earlier, and the answer to the authenticating question, “Who is the greatest football team in the world?” came easily for the Wisconsin native. “The Green Bay Packers,” Sijan replied. In continuing voice contacts, “the survivor was talking louder and faster,” the history notes. “AWOL did not know what happened to the backseater.”

The rescue force, meanwhile, was taking “ground fire from all directions” and was “worried about all the [friendly] fire hitting the survivor.” Finally, Jolly Green 15, an HH-3E helicopter, picked up a transmission from the ground: “I see you, I see you. Stay where you are. I’m coming to you!”.

For 33 minutes, Jolly Green 15 hovered over the jungle, eyes aboard searching the dense foliage below for movement. Bullets began piercing the fuselage, a few at first and then more and more. Getting no more voice contact from the ground and under a withering hail of fire, Jolly Green 15 finally left the area.

Rescue efforts the next day and electronic surveillance in the days that followed turned up no more contacts, and the search for “AWOL” was called off. One A-1E aircraft was shot down in the effort–the pilot was rescued–and several helicopter crewmen were wounded.

“If AWOL,” said the report, “only had some kind of signaling device– mirror, flare, etc.–pick-up would have been successful. The rescue of this survivor was not in the hands of man.”

Much later, a battered Lance Sijan was to ask his American cellmates, “What did I do wrong? Why didn’t I get picked up?” He told them he had lost his survival kit.

On that November day, except for enemy forces all around, Sijan was alone again. Although desperately in need of food, water and medical attention, he somehow evaded the enemy and capture as he painfully, day by day, dragged himself along the ground–toward, he hoped, freedom. But it was not to be.

Former Capt. Guy Gruters, who was to be one of Sijan’s cellmates later, told Airman: “He said he’d go for two or three days and nights–as long as he possibly could–and then he’d be exhausted and sleep. As soon as he’d wake up he’d start again, always traveling east. You’re talking 45 days now without food, and it was a max effort!”

Col. Bob Craner, the older cellmate in Hanoi, picked up the story: “When he couldn’t drag himself anymore and said, ‘This is the end,’ he saw he was on a dirt road. He lay there for a day, maybe, until a truck came along and they picked him up.

Incredibly, after a month and a half of clawing, clutching, dragging and hurting, Sijan was found three miles from where he had initially parachuted into the jungle.

Horribly emaciated and with the flesh of his buttocks worn to his hip bones, Lance Sijan still had some fight left. “He said they took him to a place where they laid him on a mat and gave him some food,” Craner related. “He said he waited until he felt he was getting a little stronger. When there was just one guard there, Captain Sijan beckoned him over. When the guy bent over to see what was the matter, Captain Sijan told me, ‘I just let him have it–wham!’ ” With the guard unconscious from a well-placed karate chop from a weakened left arm and hand, Sijan pulled himself back into the jungle. “He thought he was making it,” Craner said, “but they found him after a couple of hours.”

Once again Sijan had been robbed of precious freedom. Once again he was down, but–as other North Vietnamese were to learn–by no means out.

THE CODE OF CONDUCT

ARTICLE IV – If I become a prisoner of war, I will keep faith with my fellow prisoners. I will give no information or take part in any action which might be harmful to my comrades. If I am senior, I will take command. If not, I will obey the lawful orders of those appointed over me and will back them up in every way.

Sijan’s obsession with freedom had manifested itself much earlier, and rather uniquely, at the Air Force Academy. His arts instructor, Col. Carlin J. Kielcheski, remembers him well. “He had the crusty facade of a football player, yet he was very sensitive. I was particularly interested in those guys who broke the image of the typical artist.”

Kielcheski still has the “Humanities 499” paper Sijan submitted with his two-foot wooden sculpture of a female dancer. Sijan wrote:

“I feel that the female figure is one of nature’s purest forms. I want this statue to represent the quest for freedom by the lack of any restraining devices or objects. The theme of my sculpture is just that–a quest for freedom, an escape from the complexities of the world around us.”

Kielcheski chuckled. “Here was this bruiser of a football player coming up with these delicate kinds of things. He was not content to do what the other cadets did. He was very persistent and not satisfied with doing just any kind of job. He wanted to do it right and showed real tenacity to stick to a problem.”

Others remember different aspects of Sijan’s character. His roommate for three years, Mike Smith of Denver, said he was “probably the toughest guy mentally I’ve ever met.”

Sijan was a substitute end on the football team, Smith said. Football, he thought, hindered his academics, and his concern over grades conversely affected his performance and chances for stardom on the gridiron. “He had a lot of things going and tried to keep them all going. He came in from football practice dead tired. He’d sleep for an hour or two after dinner and then study until 1 or 2 in the morning. He knew he had to give up a lot to play football, but he had the determination to do it.”

Sijan did give up football his senior year. But one thing he did not sacrifice for studies was the company of young women.

They found him very attractive, and he had no trouble getting dates,” said Smith. “He was a big, hand some guy with a good sense of humor.” Maj. Joe Kolek, who roomed with Sijan one semester, agreed. In fact, he said, “It was pretty neat now and then to get Lance’s cast-offs.”

Smith recalls they talked sometimes about the Code of Conduct that was to test Sijan’s character so severely fewer than three years later. We found nothing wrong with the Code. We accepted the responsibility of action honorable to our country. It was strictly an extension of Lance’s personality. When he accepted something, he accepted it. He did nothing halfway. It seemed,” Smith said, “that there was always a reservoir of strength he got from his family.”

Sylvester Sijan, whose character and physique bear a striking resemblance to a middle-aged Jack Dempsey, owns the Barrel Head Grille in Milwaukee. Built into an inside wall is a mock 4-feet-around beer barrel top, a splendid woodwork fashioned by the elder Sijan from an oak table. A wooden shingle on the polished oak bears the engraved inscription, “Tradition.”

Sylvester Sijan’s forefathers immigrated from Serbia, a separate country prior to World War I that later became part of Yugoslavia. “Serbians have been noted for their heroic actions in circumstances where they were outnumbered,” the elder Sijan said. “They were vicious fighters on a one-to-one or a one-to-fifty basis, so they have a history of instinct and drive.” He thinks a mixture of that tradition, his son’s love for his home and his competitive spirit spurred him through the painful odyssey in Vietnam. What made Lance do what he did? One thing, for sure. He always wanted to come home, no matter where he was. He was going to come home whether it was in pieces or as a hero.

“Lance’s competitive nature kind of grew with him,” said Sylvester Sijan. “A person never knows how competitive he really is until he comes up against the ultimate situation. He could have been less courageous; he could have retreated into the ranks of the North Vietnamese and said, ‘Here I am, take care of me.’ But he chose to go the other way. He probably never doubted that somehow, somewhere he’d get out.”

Lance Sijan had wondered about his ultimate fate even before leaving for Vietnam, according to Mike Smith. In the Air Force at the time and stationed at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio, Smith enjoyed a visit from Sijan, who was on leave prior to going overseas. “I sensed a foreboding in him, and he and I dealt with the issue of not coming back,” Smith said. “I remember it distinctly because I talked with my wife about our conversation. I felt he had a premonition that he might not return.”

Jane Sijan, too, sensed something. In Milwaukee prior to leaving, Lance asked her to sew two extra pockets into his flight suit, and he took great pains coating matches with wax. “One night he was sitting on his bed,” she recalled. “He was sewing razor blades into his undershirts so he would have them if he was ever shot down.”

THE CODE OF CONDUCT

ARTICLE V – When questioned, should I become a prisoner of war, I am required to give name, rank, service number, and date of birth. I will evade answering further questions to the utmost of my ability. I will make no oral or written statements disloyal to my country and its allies or harmful to their cause.

Capt. Lance Sijan had been on the ground for 41 days when Col. Bob Craner and Capt. Guy Gruters took off from Phu Cat AB in their F-100 on Dec. 20, 1967. Pinpointing targets in North Vietnam from the “Misty” forward air control jet fighter, they were hit by ground fire and ejected. Both were captured and brought to a holding point in Vinh, where they were thrust into bamboo cells and chained.

Reaching back into his memory, crowded with recollections of more than five years as a prisoner of war, Craner told the story: “As best as I can recall, it was New Year’s Day of 1968 when they brought this guy in at night. The Rodent [a prison guard] came into the guy’s cell next to mine and began his interrogation. It was clearly audible. “He was on this guy for military information, and the responses I heard indicated he was in very, very bad shape. His voice was very weak. It sounded to me as though he wasn’t going to make it.

“The Rodent would say, ‘Your arm, your arm, it is very bad. I am going to twist it unless you tell me.’ The guy would say, ‘I’m not going to tell you; it’s against the Code.’ Then he would start screaming. The Rodent was obviously twisting his mangled arm. The whole affair went on for an hour and a half, over and over again, and the guy just wouldn’t give in. He’d say, ‘Wait till I get better, you S.O.B., you’re really going to get it.’ He was giving the Rodent all kinds of lip, but no information. “The Rodent kept laying into him. Finally I heard this guy rasp, ‘Sijan! My name is Lance Peter Sijan!’ That’s all he told him.”

Guy Gruters, also an Air Force Academy graduate, but a year senior to Sijan, was in a cell down the hall and did not know the identity of the third captive. He does recall that “the guy was apparently always trying to push his way out of the bamboo cell, and they’d beat him with a stick to get him back. We could hear the cracks.” After several days, when the North Vietnamese were ready to transport the Americans to Hanoi, Gruters and Craner were taken to Sijan’s cell to help him to the truck. “When I got a look at the poor devil, I retched,” said Craner. “He was so thin and every bone in his body was visible. Maybe 20 percent of his body wasn’t open sores or open flesh. Both hip bones were exposed where the flesh had been worn away.” Gruters recalled that he looked like a little guy. But then when we picked him up, I remember commenting to Bob, ‘This is one big sonofagun.”‘

While they were moving him, Craner related, “Sijan looked up and said, ‘You’re Guy Gruters, aren’t you?”

Gruters asked him how he knew, and Sijan replied, “We were at the academy together. Don’t you know me? I’m Lance Sijan.” Guy went into shock. He said, “My God, Lance, that’s not you!” “I have never had my heart-broken like that,” said Gruters, who remembered Sijan as a 220-pound football player at the academy. “He had no muscle left and looked so helpless.”

Craner said Sijan never gave up on the idea of escape in all the days they were together. “In fact, that was one of the first things he mentioned when we first went into his cell at Vinh: ‘How the hell are we going to get out of here? Have you guys figured out how we’re going to take care of these people? Do you think we can steal one of their guns?’

“He had to struggle to get each word out,” Craner said. “It was very, very intense on his part that the only direction he was planning was escape. That’s all that was on his mind. Even later, he kept dwelling on the fact that he’d made it once and he was going to make it again.” Craner remembers the Rodent coming up to them and, in a mocking voice, he paraphrased the Rodent’s message:

“Sijan a very difficult man. He struck a guard and injured him. He ran away from us. You must not let him do that anymore.”

“I never questioned the fact that Lance would make it,” said Gruters. “Now that he had help, I thought he’d come back. He had passed his low.”

The grueling truck ride to Hanoi took several days. Sijan–“in and out of consciousness, lucid for 15 seconds sometimes and sometimes an hour, but garbled and incoherent a lot,” according to Craner–told the story of his 45-day ordeal in the jungle while the trio were kept under a canvas cover during the day. The truck ride over rough roads at night, with the Americans constantly bouncing 18 inches up and down in the back, was torture itself. Craner and Gruters took turns struggling to keep an unsecured 55-gallon drum of gasoline from smashing them while the other cradled Sijan between his legs and cushioned his head against the stomach. “I thought he had died at one point in the trip,” said Craner. “I looked at Guy and said, ‘He’s dead.’ Guy started massaging his face and neck trying to bring him around. Nothing. I sat there holding him for about two hours, and suddenly he just came around. I said, ‘OK, buddy, my hat’s off to you.”‘

Finally reaching Hanoi, the three were put into a cell in “Little Vegas.” Craner described the conditions: “It was dark, with open air, and there was a pool of water on the worn cement floor. It was the first time I suffered from the cold. I was chilled to the bone, always shivering and shaking. Guy and I started getting respiratory problems right away, and I couldn’t imagine what it was doing to Lance. That, I think, accounts ultimately for the fact that he didn’t make it.”

“Lance was always as little of a hindrance to us as he could be,” said Gruters. “He could have asked for help any one of a hundred thousand times, but he never asked for a damned thing! There was no way Bob and I could feel sorry for ourselves.”

Craner said a Vietnamese medic gave Sijan shots of yellow fluid, which he thought were antibiotics. The medic did nothing for his open sores and wounds, and when he looked at Sijan’s mangled hand, “he just shook his head.” The medic later inserted an intravenous tube into Sijan’s arm, but Sijan, fascinated with it in his subconscious haze, pulled it out several times. Thus, Craner and Gruters took turns staying awake with him at night.

“One night,” the colonel said, “a guard opened the little plate on the door and looked in, and there was Lance beckoning to the guard. It was the same motion he told me he had made to the guy in the jungle, and I could just see what was going through the back reaches of his mind: ‘If I can just get that guy close enough. . . .”‘ He remembers that Sijan once asked them to help him exercise so he could build up his strength for another escape attempt. “We got him propped up on his cot and waved his arms around a few times, and that satisfied him. Then he was exhausted.” At another point, Sijan became lucid enough to ask Craner, “How about going out and getting me a burger and french fries?” But Sijan’s injuries and now the respiratory problem sapped his strength. “First he could only whisper a word, and then it got down to blinking out letters with his eyes,” said Gruters. “Finally he couldn’t do that anymore, even a yes or no.”

With tears glistening, Bob Craner remembered when it all came to an end. They had been in Hanoi about eight days. “One night Lance started making strangling sounds, and we got him to sit up. Then, for the first time since we’d been together, his voice came through loud and clear. He said, ‘Oh my God, it’s over,’ and then he started yelling for his father. He’d shout, ‘Dad, Dad, where are you? Come here, I need you!’

“I knew he was sinking fast. I started beating on the walls, trying to call the guards, hoping they’d take him to a hospital. They came in and took him out. As best as I could figure it was January 21.” “He had never asked for his dad before,” said Gruters, “and that was the first time he’d talked in four or five days. It was the first time I saw him display any emotion. It was absolutely his last strength.

It was the last time we saw him.” A few days later, Craner met the camp commander in the courtyard while returning from a bathhouse and asked him where Sijan was. “Sijan spend too long in the jungle,” came the reply. “Sijan die.”

Guy Gruters talked some more about Sijan: “He was a tremendously strong, tough, physical human being. I never heard Lance complain. If you had an army of Sijans, you’d have an incredible fighting force.”

Said Craner: “Lance never talked about pain. He’d yell out in pain sometimes, but he’d never dwell on it like, ‘Damn, that hurts.’ “Lance was so full of drive whenever he was lucid. There was never any question of, ‘I hurt so much that I’d rather be dead.’ It was always positive for him, pointed mainly toward escape but always toward the future.”

Craner recommended Sijan for the Medal of Honor. Why? “He survived a terrible ordeal, and he survived with the intent, sometime in the future, of picking up the fight. Finally he just succumbed.” “There is no way you can instill that kind of performance in an individual. l don’t know how many we’re turning out like Lance Sijan, but I can’t believe there are very many.”

THE CODE OF CONDUCT

ARTICLE VI – I will never forget that I am an American fighting man, responsible for my actions, and dedicated to the principles which made my country free. I will trust in my God and in the United States of America.

In Milwaukee, Sylvester Sijan started to bring up the point, and then he hesitated. He finally did, though, and then he talked about it unabashedly. “I remember one day in January, about the same time that year, driving down the expressway; I was feeling despondent, and I began screaming as loud as I could, things like, ‘Lance, where are you?’ I may have murmured such things to myself before, but I never yelled as loud as I did that day.” He wonders if maybe–just maybe–it may have been at the same time Lance was calling for him in Hanoi. “The realization that Lance’s final thoughts were what they were makes me feel most humble, most penitent, and yet somehow profoundly honored,” he said. He still wears a POW bracelet with Lance’s name on it. “I just can’t take it off,” he said, adding that “not too many people realize its significance anymore.”

Though Lance was declared missing in action, and though one package they sent to him in Hanoi came back stamped “deceased”–“which jarred me terribly,” Jane Sijan said–the family never gave up hope. “I’m such an optimist,” she said. “I even watched all the prisoners get off the planes on television [in 1973] hoping there had been some mistake.”

Lance’s body, along with the headstone used to mark his grave in North Vietnam, was returned to the United States in 1974 for interment in Milwaukee (23 other bodies were returned to the United States at the same time). At a memorial service in Bay View High School, the family announced the Captain Lance Peter Sijan Memorial Scholarship Fund.

“It is a $500 scholarship presented yearly to a graduate male student best exemplifying Lance’s example of the American boy,” said Jane. “It will be a lifetime effort on our behalf and will be carried on by our children.”

Lance Sijan, U.S. Air Force Academy Class of 1965, would be 72 years old now. He is the first academy graduate to be awarded the Medal of Honor. A dormitory at the academy was named Sijan Hall in his honor. “The man represented something,” Sylvester Sijan said of his son. “The old cliche that he was a hero and represented guts and determination is true. That’s what he really represented. How much of that was really Lance? What he is, what he did, the facts are there.” “We’ll never adjust to it,” he said. “People say, ‘It’s been a long time ago and you should be OK now,’ but it stays with you and well it should.”

“Lance was always such a pleasure; he was an ideal son, but then all our children are a joy and blessing to us,” said Jane Sijan. “It still hurts to talk about it, but I have certainly accepted it. I’m a very patient woman, and I wait for the day our family will all be together again, that’s all.”

On March 4, 1976, three other former prisoners of war, all living, also received Medals of Honor from President Ford. One of them was Air Force Col. George E. “Bud” Day [“All Day’s Tomorrows,” Airman, November 1976]. Col. Day later wrote to Airman: “Lance was the epitome of dedication, right to death! When people ask about what kind of kids we should start with, the answer is: straight, honest kids like him. They will not all stay that way–but by God, that’s the minimum to start with.”

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 8

SERVICE:

U.S. Marine Corps 1942-1945

U.S. Army Reserve 1946-1949

Iowa Air National Guard 1949-1951

U.S. Air Force 1951-1977

World War II 1942-1945

Cold War 1945-1977

Korean War 1953

Vietnam War 1967-1973 (POW)

Bud Day was born on February 24, 1925, in Sioux City, Iowa. He enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps on December 10, 1942, and spent 30 months in the South Pacific during World War II before receiving an honorable discharge on November 24, 1945.

After the war, Day joined the U.S. Army Reserve on December 11, 1946, and served until December 10, 1949. He was appointed a 2d Lt in the Iowa Air National Guard on May 17, 1950, and went on active duty in the U.S. Air Force on March 15, 1951.

Lt Day completed pilot training and was awarded his pilot wings at Webb AFB, Texas, in September 1952, and completed All-Weather Interceptor School and Gunnery School in December 1952. He served as an F-84 Thunder jet pilot with the 559th Strategic Fighter Squadron of the 12th Strategic Fighter Wing at Bergstrom AFB, Texas, from February 1953 to August 1955, with deployments to Omisawa, Japan, during this time in support of the Korean War.

His next assignment was as an F-84 and F-100 Super Sabre pilot with the 55th Fighter Bomber Squadron of the 20th Fighter Bomber Wing and later on the wing staff at RAF Wethersfield, England, from August 1955 to June 1959, followed by service as an Assistant Professor of Aerospace Science at the Air Force ROTC detachment at St. Louis University in St. Louis, Missouri, from June 1959 to August 1963. During his service in England, he became the first person ever to live through a no-chute bailout from a jet fighter.

CPT Day attended Armed Forces Staff College for Counterinsurgency Indoctrination training at Norfolk, Virginia, from August 1963 to January 1964, and then served as an Air Force Advisor to the New York Air National Guard at Niagara Falls Municipal Airport, New York, from January 1964 to April 1967.

MAJ Day then deployed to Southeast Asia, serving first as an F-100 Assistant Operations Officer at Tuy Hoa AB, South Vietnam, before organizing and serving as the first commander of the Misty Super FACs at Phu Cat AB, South Vietnam, from June 1967 until he was forced to eject over North Vietnam and was taken as a Prisoner of War on August 26, 1967. He managed to escape from his captors and make it into South Vietnam before being recaptured and taken to Hanoi. After spending 2,028 days in captivity, COL Day was released during Operation Homecoming on March 14, 1973. He was briefly hospitalized to recover from his injuries at March AFB, California, and then received an Air Force Institute of Technology assignment to complete his PhD in Political Science at Arizona State University from August 1973 to July 1974.

His final assignment was as an F-4 Phantom II pilot and Vice Commander of the 33rd Tactical Fighter Wing at Eglin AFB, Florida, from September 1974 until his retirement from the Air Force on December 9, 1977. MISTY 1, Col Bud Day, died on July 27, 2013, and was buried at Barrancas National Cemetery at NAS Pensacola, Florida.

His Medal of Honor Citation reads:

On 26 August 1967, Col. Day was forced to eject from his aircraft over North Vietnam when it was hit by ground fire. His right arm was broken in 3 places, and his left knee was badly sprained. He was immediately captured by hostile forces and taken to a prison camp where he was interrogated and severely tortured. After causing the guards to relax their vigilance, Col. Day escaped into the jungle and began the trek toward South Vietnam. Despite injuries inflicted by fragments of a bomb or rocket, he continued southward surviving only on a few berries and uncooked frogs. He successfully evaded enemy patrols and reached the Ben Hai River, where he encountered U.S. artillery barrages. With the aid of a bamboo log float, Col. Day swam across the river and entered the demilitarized zone. Due to delirium, he lost his sense of direction and wandered aimlessly for several days. After several unsuccessful attempts to signal U.S. aircraft, he was ambushed and recaptured by the Viet Cong, sustaining gunshot wounds to his left hand and thigh. He was returned to the prison from which he had escaped and later was moved to Hanoi after giving his captors false information to questions put before him. Physically, Col. Day was totally debilitated and unable to perform even the simplest task for himself. Despite his many injuries, he continued to offer maximum resistance. His personal bravery in the face of deadly enemy pressure was significant in saving the lives of fellow aviators who were still flying against the enemy. Col. Day’s conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Air Force and reflect great credit upon himself and the U.S. Armed Forces.

Recent Comments