Save Our Sacred Sites . . . . STOP the Lancaster Pipeline

For months, Native Americans have been scouring fields in southwestern Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, finding proof of their Native American ancestors who once called it home. Discovered artifacts include pottery shards, stone tools, and beads to name a few. Seven new archaeological sites have been registered with the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

Why is this of great concern? Why instead of joy is there anger and anxiety? These sacred grounds have been located along the path of a proposed natural gas pipeline which will take gas to be shipped from Cove Point, Maryland to companies and people overseas. None of the gas will be used for the community. Will all the findings and work make a difference in the ultimate location of the pipeline . . . Who Knows?

August 2014, Williams Partners (Williams), the Oklahoma-based company that will build the Central Penn Line South pipeline, told federal regulators its survey of “cultural resources” along the proposed route was nearly complete. There is, the company acknowledged, a “significant degree of cultural resource sensitivity” in Lancaster County; so the company devoted extra time and scrutiny to investigating the path.

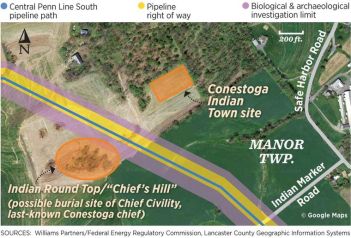

The maps haven’t changed – The route still cuts through several known archaeological sites, including Conestoga Indian Town — perhaps the most important Native American cultural site in Pennsylvania.

Williams officials say the maps will change by the time the company submits its official application to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in March 2015. Williams will not say exactly how the maps will be revised. Native Americans and their allies are not taking the company’s word for it. Why should they? What has been the experience of the Native American with companies when it comes to protection of sacred grounds?

they? What has been the experience of the Native American with companies when it comes to protection of sacred grounds?

If all else fails, members of the American Indian Movement (AIM) last week reiterated a vow to block bulldozers to stop the pipeline from being built: “Everyone has been telling [Williams] about how sacred this land is, and it means nothing to them,” said Carlos Whitewolf, a local Native American leader. “We have gotten support from a lot of AIM members, from out-of-state as well,” he said. “When the time comes, we will have some people down here.”

As part of its cultural resource survey, Williams dug at 15-meter intervals along a 300-foot-wide corridor paralleling the proposed path, looking for artifacts. The company has worked closely with the Pennsylvania Museum and Historical Commission; detailed survey reports won’t be publicly available until the company files its application later this year.

Federal law requires pipeline companies to conduct surveys and attempt to go around — even under — any cultural resources they find. In addition to evaluating the route, Williams reached out to 35 Native American tribes, seeking input. But NO ONE reached out to the local Native American opponents of the pipeline – the Native American residents of Lancaster County.

“It would have been nice if Williams had put something in the newspaper, ‘Calling all Native Americans,’ ” said MaryAnn Robins, President of the Circle Legacy Center, a local Native American group. “I have no qualms about going to meet with [the company]. In fact, I challenge them to meet with me.”

In part, the disconnect may be due to the fact that the last of the Susquehannocks, or Conestogas, who once populated this area were killed in the infamous “Conestoga Massacre” of 1783; the tribe no longer exists. But Robins, who traces her lineage to the Onondaga, said Native Americans share a sense of collective history — and outrage when they think it’s being defiled.

The Circle Legacy Center drafted a letter it hopes to have published in Native American newspapers with national circulation, including Indian Country Today and the Native American Times. “We collectively condemn the planning, authorization and construction” of the pipeline, the letter asserts. Of particular concern is the pipeline’s route through “Conestoga Indian Town,” land set aside for the Susquehannocks by William Penn in Manor Township; it is, the letter asserts, “the most significant Native American site in all of Pennsylvania.”

Current maps show the pipeline bisecting it, running between the site where six Susquehannocks were slaughtered during the “Conestoga Massacre” to the northeast, and “Indian Round Top,” which some Native Americans also call “Chief’s Hill.” It may be the burial site of Chief Civility, the last of the Susquehannock chiefs. “Nearly the entire block between Brenneman Road, Safe Harbor Road, Indian Marker Road, and Highville Road was Conestoga Indian Town,” said Darvin Martin, a local historian who has studied the area. “There are certainly graves throughout,” and even if Chief Civility is not buried on Indian Round Top, Martin said it almost certainly was used as a sight tower to send smoke signals north and south.

Current maps show the pipeline bisecting it, running between the site where six Susquehannocks were slaughtered during the “Conestoga Massacre” to the northeast, and “Indian Round Top,” which some Native Americans also call “Chief’s Hill.” It may be the burial site of Chief Civility, the last of the Susquehannock chiefs. “Nearly the entire block between Brenneman Road, Safe Harbor Road, Indian Marker Road, and Highville Road was Conestoga Indian Town,” said Darvin Martin, a local historian who has studied the area. “There are certainly graves throughout,” and even if Chief Civility is not buried on Indian Round Top, Martin said it almost certainly was used as a sight tower to send smoke signals north and south.

MaryAnn Robins is more succinct: “its sacred grounds.”

Opponents of the pipeline are organizing, trying to draw national attention to the cause, reaching out to Hollywood and music industry celebrities they think might be sympathetic. Pipeline opponents have also sent pleas to actor Leonardo DiCaprio, singer Neil Young and ESPN host Keith Olbermann, among others, seeking support. The group also has taken to social media with its “Save Lancaster County’s Sacred Native American Grounds” page. The threats, or promises, to take physical action were reiterated, when Whitewolf told a crowd at a Conestoga Fire Hall pipeline meeting that “We will show up in big numbers, and you will have a war on your hands.” Gene Thunderwolf, another local Native American opponent: “We are not afraid to occupy.”

Robin Maguire says there is no promise the route of the pipeline will change. Williams has long known about Conestoga Indian Town and other culturally sensitive sites along the route. “Six months ago we had a private meeting with Williams,” she said. “We showed them all our findings and they were blown away by what we showed them. Now here we are, looking at these same maps again.” Ms Robins is not willing to bet they’ll change. “There’s so much cultural history around here,” she said. “We can’t let them just erase it away.”

Let’s look at the Susquehannock History.

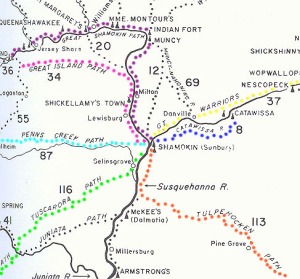

The story begins with Captain John Smith of Jamestown fame, who, while exploring the upper Chesapeake Bay in 1608, had the first recorded European encounter with the native people known as the Susquehannock. That name, as well as the name for the Susquehanna River, is derived from the word Sasquesahanough, a descriptive term used by Smith’s Algonquian interpreter to mean People at the Falls, or People of the Muddy River. Historically, we often come to know tribal groups by the name that others call them, and not what they call themselves. Of course, this trend arises naturally from the fact that most tribes simply call themselves the People, and all others are the Others. How they differentiate among groups of others is how a name becomes attached to a tribe.

In the case of the Susquehannocks, colonial history records numerous names which can be associated with this tribe. The true nature of their society, whether composed of a single tribe in a single village, or a confederacy of smaller tribes occupying scattered villages, will probably never be known, since Europeans seldom visited this inland region during the early colonial period. It’s likely that the Susquehannocks had occupied the same land for several hundred years. What is known is that at the time of the Jamestown settlement in Virginia, the Susquehannocks controlled a vast territory, composed of the Susquehanna River and its tributaries, from what is now New York, across Pennsylvania, to Maryland. They had a formidable village in the lower river valley near present-day Lancaster, Pennsylvania, when Captain Smith met them. He estimated the population of their village to be two thousand, although he never visited it. Modern estimates of their population, including the whole territory in 1600, range as high as seven thousand. But the story of the Susquehannocks has a violent and tragic end. Within a hundred and fifty years, this once powerful tribe was completely obliterated.

During the 1600′s, the Susquehannocks, like many eastern tribes, were constantly forming alliances and waging wars with their neighbors, both native and European, for control and profit. Historically, the Susquehannocks had always been allies of the Huron and enemies of the Iroquois. During this time they were known to combat other tribes as well, such as the Delaware to the east, the Powhatan to the south, and the Mohawk to the north. Besides control of their native land and its natural trading routes, the Susquehannocks were fighting for the profits of business with the European fur traders. They were perhaps the only tribe to achieve friendly relations with all the Europeans: the French, the Dutch, the Swedes, and the English, at one time or another. They signed treaties with colonial governors of New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia.

During the 1600′s, the Susquehannocks, like many eastern tribes, were constantly forming alliances and waging wars with their neighbors, both native and European, for control and profit. Historically, the Susquehannocks had always been allies of the Huron and enemies of the Iroquois. During this time they were known to combat other tribes as well, such as the Delaware to the east, the Powhatan to the south, and the Mohawk to the north. Besides control of their native land and its natural trading routes, the Susquehannocks were fighting for the profits of business with the European fur traders. They were perhaps the only tribe to achieve friendly relations with all the Europeans: the French, the Dutch, the Swedes, and the English, at one time or another. They signed treaties with colonial governors of New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia.

But the price of constant warfare, along with the ravages of disease, took its toll. As warriors were killed in battle by the hundreds, their numbers quickly declined, and the social structure began to fail. Smallpox epidemics devastated their population at least twice. Many Susquehannocks left their homeland to join other tribes in New York, North Carolina, and Ohio. By the end of the 1600′s, only a few hundred Susquehannocks remained as an identifiable tribe. After migrating as far away as Virginia, they returned to their ancestral home to build a new village, where they lived under the protection of the provincial government of Pennsylvania. Here they were known as the Conestoga, referring to the name of their village, Conestoga Town on the Conestoga River. Some historians have suggested that Conestoga may well have been what the Susquehannock called themselves all along, but the evidence is circumstantial at best.

Conestoga Town quickly became an important center for trade and treaty signings. William Penn himself visited in 1700, as did several succeeding governors of the Commonwealth. Its importance may have been more symbolic than practical, for here was a genuine Indian community, friendly to the colonial settlers, within easy travel distance of the politicians in Philadelphia. The historical record is replete with references to the politicking at Conestoga Town during the first few decades of the 1700′s, but it is remarkably vacant of any meaningful insight into the daily life at Conestoga Town (or even exactly where the town was located!). Although no official censuses were kept, documents of the day suggest that the population of this small, isolated tribe declined steadily, from more than a hundred to a few dozen, within two generations.

The final chapter of the Susquehannocks is well documented in the historical record. In 1763, Chief Pontiac of the Ottawas led uprisings against settlers in the Great Lakes region, including western Pennsylvania. Although the Conestoga were peaceful farmers and craftsman, with no connection to the rebellion in the west, they were attacked by a vigilante group known as the Paxton Boys, who found the Conestoga an easy target. The Paxton Boys murdered the six people they found in the village. The provincial council ordered the rest of the Conestoga to be taken into protective custody, but the measures failed. The Paxton Boys broke into the workhouse and slaughtered all fourteen members of the tribe. Two residents of Conestoga survived the attacked only because they had been away working at another farm. They were a husband and wife known as Michael and Mary. Governor John Penn eventually issued them papers of protection until their death. When they died, the history of the Susquehannocks died with them.

Final Census of the Conestoga, recorded by Lancaster County Sheriff John Hays, 1763

Murdered at Conestoga Town:

• Sheehays • Wa-a-shen (George)

• Tee-Kau-ley (Harry) • Ess-canesh (son of Sheehays)

• Tea-wonsha-i-ong (an old woman) • Kannenquas (a woman)

Murdered at the Lancaster Workhouse:

• Kyunqueagoah (Captain John) • Koweenasee (Betty, his wife)

• Tenseedaagua (Bill Sack) • Kanianguas (Molly, his wife)

• Saquies-hat-tah (John Smith) • Chee-na-wan (Peggy, his wife)

• Quaachow (Little John, Capt John’s son) • Shae-e-kah (Jacob, a boy)

• Ex-undas (Young Sheehays, a boy) • Tong-quas (Chrisly, a boy)

• Hy-ye-naes (Little Peter, a boy) • Ko-qoa-e-un-quas (Molly, a girl)

• Karen-do-uah (a little girl) • Canu-kie-sung (Peggy, a girl)

Survivors on the farm of Christian Hershey:

• Michael • Mary (his wife)

The fate of the Susquehannock was by no means unique. In fact, it was worse for most eastern tribes. In the first few decades of colonial settlement, native peoples who inhabited the coastal regions, including whole tribes, were wiped out at an astonishing rate. Many of their names are lost to history. For the Susquehannock, although the tribe ceased to exist as a consolidated community, their legacy remains with the descendants who survive to embrace their lineage, and with the name that will never be forgotten. As long as the Susquehanna River flows to the sea, we will remember the Susquehannocks.

Our job now is to protect where our Native American ancestors lived and their burial sites from ultimate desecration and destruction by Williams. It is a matter of history, honor, and respect for our Native American ancestors.

~~~Cherokee

Recent Comments