Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? – Chapter 27 – Bray

For many people this article will intensify the conflict regarding women serving in combat roles in the military. However when one reviews the history of wars involving the United States, one will discover many women have served not only in traditional combat roles, also in roles of espionage and infiltration traditionally held by men.

Former U.S. Army Capt. Linda L. Bray says her male superiors were incredulous upon hearing she had ably led a platoon of military police officers through a firefight during the 1989 invasion of Panama. (Operation Just Cause)

Former U.S. Army Capt. Linda L. Bray says her male superiors were incredulous upon hearing she had ably led a platoon of military police officers through a firefight during the 1989 invasion of Panama. (Operation Just Cause)

Instead of being lauded for her actions, the first woman in U.S. history to lead male troops in combat said higher-ranking officers accused her of embellishing accounts of what happened when her platoon bested an elite unit of the Panamanian Defense Force. After her story became public, Congress fiercely debated whether she and other women had any business being on the battlefield.

The Pentagon’s longstanding prohibition against women serving in ground combat ended in 2013, when then-Defense Secretary Leon Panetta announced that most combat roles jobs will now be open to female soldiers and Marines. Panetta said women are integral to the military’s success and will be required to meet the same physical standards as their male colleagues.

“I’m so thrilled, excited. I think it’s absolutely wonderful that our nation’s military is taking steps to help women break the glass ceiling,” said Bray, 54, of Clemmons, N.C. “It’s nothing new now in the military for a woman to be right beside a man in operations.”

The end of the ban on women in combat comes more than 23 years after Bray made national news and stoked intense controversy after her actions in Panama were praised as heroic by Marlin Fitzwater, the spokesman for then-President George H.W. Bush.

Bray and 45 soldiers under her command in the 988th Military Police Company, nearly all of them men, encountered a unit of Panamanian special operations soldiers holed up inside a military barracks and dog kennel.

Her troops killed three of the enemy and took one prisoner before the rest were forced to flee, leaving behind a cache of grenades, assault rifles and thousands of rounds of ammunition, according to Associated Press news reports published at the time. The Americans suffered no casualties. Citing Bray’s performance under fire as an example, Rep. Patricia Schroeder, D-Colo., introduced a bill to repeal the law that barred female U.S. military personnel from serving in combat roles. But the response from the Pentagon brass was less enthusiastic. Schroder’s bill died after top generals lobbied against the measure, saying female soldiers just weren’t up to the physical rigors of combat.

“The responses of my superior officers were very degrading, like, ‘What were you doing there?'” Bray said. “A lot of people couldn’t believe what I had done, or did not want to believe it. Some of them were making excuses, saying that maybe this really didn’t happen the way it came out.”

“The routine carrying of a 120-pound rucksack day in and day out on the nexus of battle between infantrymen is that which is to be avoided and that’s what the current Army policy does,” Gen. M.R. Thurman, then the head of the U.S. Southern Command, testified before the Senate Armed Services Committee.

For Bray, the blowback got personal.

The Army refused to grant her and other female soldiers who fought on the ground in Panama the Combat Infantryman Badge. She was awarded the Army Commendation Medal for Valor, an award for meritorious achievement in a non-combat role.

Bray was also the subject of an Army investigation over allegations by Panamanian officials that she and her soldiers had destroyed government and personal property during the invasion that toppled Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega.

Though eventually cleared of any wrongdoing, the experience soured Bray on the Army. In 1991, she resigned her commission after eight years of active duty and took a medical discharge related to a training injury.

Today’s military is much different from the one Bray knew, with women already serving as fighter pilots, aboard submarines and as field supervisors in war zones. But some can’t help but feel that few know of their contributions, said Alma Felix, 27, a former Army specialist.

“We are the support. Those are the positions we fill and that’s a big deal — we often run the show — but people don’t see that,” Felix said. “Maybe it will put more females forward and give people a sense there are women out there fighting for our country. It’s not just your typical poster boy, GI Joes doing it.”

(Information for this article was gathered from newspapers, military documents and interviews)

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 20

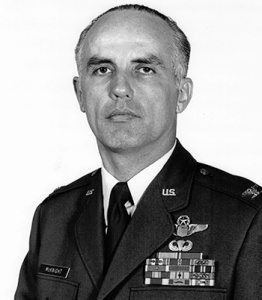

MCKNIGHT, GEORGE GRISBY

MCKNIGHT, GEORGE GRISBY

Branch/Rank: UNITED STATES AIR FORCE/O3

Unit: 602 ACS

Home City of Record: ALBANY OR

Date of Loss: 06-November-65

Country of Loss: NORTH VIETNAM

Aircraft/Vehicle/Ground: A1E

Missions: 50+MISSION

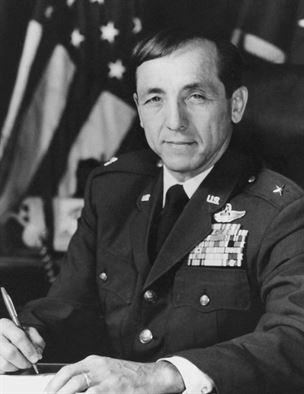

Colonel O-6, U.S. Air Force

U.S. Air Force Reserve 1955-1956

U.S. Air Force 1956-1986

Cold War 1955-1986

Vietnam War 1964-1973 (POW)

George McKnight was born in 1933 in Albany, Oregon. He was commissioned a 2d Lt in the U.S. Air Force through the Air Force ROTC program on July 15, 1955, and went on active duty beginning January 23, 1956. Lt McKnight completed pilot training and was awarded his pilot wings at Laredo AFB, Texas, in February 1957, and then completed F-100 Super Sabre Combat Crew Training in September 1957.

His first assignment was as an F-100 pilot with the 35th Fighter-Bomber Squadron at Itazuke AB, Japan, from October 1957 to June 1961 followed by service as an F-100 pilot with the 428th and then the 430th Tactical Fighter Squadron at Cannon AFB, New Mexico, from July 1961 to January 1965.

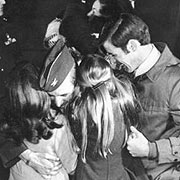

During this time, he deployed to Southeast Asia and flew combat missions from Takhli Royal Thai AFB, Thailand, from November to December 1964. Capt McKnight next completed A-1 Skyraider training at Eglin AFB, Florida, and then served as an A-1 pilot with the 602nd Fighter Squadron at Bien Hoa AB, South Vietnam, from July 1965 until he was forced to bail out over North Vietnam and was taken as a Prisoner of War on November 6, 1965. McKnight, a captain at the time, was taken as a POW in November 1965. He was an A-1 Skyraider pilot, assigned to the 602nd Fighter Squadron at Bien Hoa Air Base, South Vietnam. After spending 2,656 days in captivity, Col McKnight was released during Operation Homecoming on February 12, 1973. He was briefly hospitalized to recover from his injuries at Travis AFB, California, and then attended the Air War College at Maxwell AFB, Alabama, from August 1973 to July 1974.

Speaking about his POW experience, COL McKnight states:

“I was a POW for 7 years, 3 months, 2 days, 4 hours and 3 minutes,” he said of the confinement that lasted until the end of the war. He and 10 others, including U.S. Sen. John McCain, had a name for their prison and for themselves. “We called it Alcatraz Prison and ourselves the Alcatraz 11. We were all in solitary confinement.”

McKnight said he never saw his fellow American prisoners until they were released, with the exception of one escape attempt. Prisoners were kept in individual cells and communicated with one another by tapping on the walls — a code they learned in case they were captured.

“It was exactly like text messaging,” he said with a laugh. “So we invented it. We want our money back.”

When he returned to the Air Force War College in Montgomery, Ala., he met a woman in the Nurse Corps. He and Suzanne married, and 34 years later are “living happily ever after.”

To McKnight, Veterans Day is a time to especially honor the country’s young service men and women.

“It’s amazing they can get those men and women without the threat of the draft,” he said, his voice catching with emotion. “Those guys today are volunteers. So they are very special soldiers.”

His next assignment was to flight retraining and F-4 Phantom II Combat Crew Training before serving as Special Assistant to the Deputy Chief of Operations for the 463rd Tactical Fighter Squadron at RAF Lakenheath, England, from March 1975 to April 1976.

COL McKnight then served as Deputy Commander for Operations of the 32nd Tactical Fighter Squadron at Camp New Amsterdam in the Netherlands from May 1976 to March 1978, followed by studies at the Defense Language Institute and then service as Defense Air Attaché to the Democratic Republic of the Congo from October 1978 to May 1982. His final assignment was as Commander in Chief of the U.S. Air Force/Canadian Forces Officer Exchange Program in Ottawa City, Canada, from November 1982 until his retirement from the Air Force on March 1, 1986.

His Air Force Cross Citation reads:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Section 8742, Title 10, United States Code, awards the Air Force Cross to Lieutenant Colonel George G. McKnight for extraordinary heroism in military operations against an opposing armed force while a Prisoner of War in North Vietnam on 12 October 1967. On that date, he executed an escape from a solitary confinement cell by removing the door bolt brackets from his door. Colonel McKnight knew the outcome of his escape attempt could be severe reprisal or loss of his life. He succeeded in making it through a section of housing, then to the Red River and swam down river all night. The next morning he was recaptured, severely beaten, and put into solitary confinement for two and a half years. Through his extraordinary heroism and aggressiveness in the face of the enemy, Colonel McKnight reflected the highest credit upon himself and the United States Air Force.

Have We Forgotten Our Heroes? Chapter 17

Name: Samuel Robert Johnson

Name: Samuel Robert Johnson

Rank/Branch: O4/United States Air Force

Unit: 433rd TFS

Date of Birth: 11 October 1930

Home City of Record: Dallas TX

Date of Loss: 16 April 1966

Country of Loss: North Vietnam

Status (in 1973): Returnee

Aircraft/Vehicle/Ground: F4C

Missions: 25

NOTE: Flew 62 missions in Korea in F-86’s

Samuel Robert “Sam” Johnson (born October 11, 1930) is a retired career U.S. Air Force officer and fighter pilot and an American politician. He currently is a Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives from the 3rd District of Texas. The district includes much of Collin County, as well as Plano, where he lives.

Johnson grew up in Dallas and graduated from Woodrow Wilson High School. Johnson graduated from Southern Methodist University in his hometown in 1951, with a degree in business administration. While at SMU, Johnson joined the Delta Chi social fraternity as well as the Alpha Kappa Psi business fraternity. He served a 29-year career in the United States Air Force, where he served as director of the Air Force Fighter Weapons School and flew the F-100 Super Sabre with the Air Force Thunderbirds precision flying demonstration team. He commanded the 31st Tactical Fighter Wing at Homestead AFB, Florida and an air division at Holloman AFB, New Mexico, retiring as a Colonel.

He is a veteran of both the Korean and Vietnam Wars as a fighter pilot. During the Korean War, he flew 62 combat missions in the F-86 Sabre. During the Vietnam War, Johnson flew the F-4 Phantom II.

In 1966, while flying his 25th combat mission in Vietnam, he was shot down over North Vietnam. He was a prisoner of war for seven years, including 42 months in solitary confinement. During this period, he was repeatedly tortured.

Johnson was part of a group of 12 prisoners known as the Alcatraz Gang, a group of prisoners separated from other captives for their resistance to their captors. They were held in “Alcatraz”, a special facility about one mile away from the Hỏa Lò Prison, notably nicknamed the “Hanoi Hilton”. Johnson, like the others, was kept in solitary confinement, locked nightly in irons in a 3-by-9-foot cell with the light on around the clock. Johnson recounted the details of his POW experience in his autobiography, Captive Warriors(available through amazon).

Mr. Johnson states “The nearly seven years that I spent in Hanoi but most especially the more than two years in a camp called Alcatraz engendered a close-knit bond between me and some great Americans. I count these men as true friends and their courage and ideals have brought home vividly to me what America is all about. I can only emphasize that the freedoms that most Americans take for granted are in fact, real and must be preserved. I have returned to a great nation and our sacrifices have been well worth the effort. I pledge to continue to serve and fight to protect the freedoms and ideals that the United States stands for” and he has done so.”

A decorated war hero, Johnson was awarded two Silver Stars, two Legions of Merit, the Distinguished Flying Cross, one Bronze Star with Combat “V” for Valor, two Purple Hearts, four Air Medals, and three Air Force Outstanding Unit Awards. He was also retroactively awarded the Prisoner of War Medal following its establishment in 1985. He walks with a noticeable limp, due to an old war injury.

After his military career, he established a homebuilding business in Plano. He was elected to the Texas House of Representatives in 1984 and was re-elected four times. In 1990, Johnson was inducted into the Woodrow Wilson High School Hall of Fame. In October 2009, the Congressional Medal of Honor Society awarded Johnson the National Patriot Award, the Society’s highest civilian award given to Americans who exemplify patriotism and strive to better the nation.

On May 8, 1991, he was elected to the House in a special election brought about by eight-year incumbent Steve Bartlett’s resignation to become mayor of Dallas. Johnson defeated fellow conservative Republican Thomas Pauken, also of Dallas, 24,004 (52.6 percent) to 21,647 (47.4 percent). Johnson thereafter won a full term in 1992 and has been reelected nine times. The 3rd has been in Republican hands since 1968. The Democrats did not even field a candidate in 1992, 1994, 1998, or 2004.

2004: Johnson ran unopposed by the Democratic Party in his district in the 2004 election. Paul Jenkins, an independent, and James Vessels, a member of the Libertarian Party ran against Johnson. Johnson won overwhelmingly in a highly Republican district. Johnson garnered 86% of the vote (178,099), while Jenkins earned 8% (16,850) and Vessels 6% (13,204).

2006: Johnson ran for re-election in 2006, defeating his opponent Robert Edward Johnson in the Republican primary, 85 to 15 percent. In the general election, Johnson faced Democrat Dan Dodd and Libertarian Christopher J. Claytor. Both Dodd and Claytor are West Point graduates. Dodd served two tours of duty in Vietnam and Claytor served in Operation Southern Watch in Kuwait in 1992. It was only the fourth time that Johnson had faced Democratic opposition. Johnson retained his seat, taking 62.5% of the vote, while Democrat Dodd received 34.9% and Libertarian Claytor received 2.6%. However, this was far less than in years past, when Johnson won by margins of 80 percent or more.

2008: Johnson retained his seat in the House of Representatives by defeating the Democrat Tom Daley and Libertarian nominee Christopher J. Claytor in the 2008 general election. He won with 60 percent of the vote, an unusually low total for such a heavily Republican district.

2010: Johnson won re-election with 66.3% of the vote against Democrat John Lingenfelder (31.3%) and Libertarian Christopher Claytor (2.4%).

2014: Johnson handily won re-nomination to his thirteenth term, twelfth full term, in the U.S. House in the Republican primary held on March 4, 2014. He polled 30,943 votes (80.5 percent); two challengers, Josh Loveless and Harry Pierce, held the remaining combined 19.5 percent of the votes cast.

In the House, Johnson is an ardent conservative. By some views, Johnson had the most conservative record in the House for three consecutive years, opposing pork barrel projects of all kinds, voting for more IRAs and against extending unemployment benefits. The conservative watchdog group Citizens Against Government Waste has consistently rated him as being friendly to taxpayers. Johnson is a signer of Americans for Tax Reform’s Taxpayer Protection Pledge. Johnson is a member of the conservative Republican Study Committee, and joined Dan Burton, Ernest Istook and John Doolittle in re-founding it in 1994 after Newt Gingrich pulled its funding. He alternated as chairman with the other three co-founders from 1994 to 1999, and served as sole chairman from 2000 to 2001.

On the Ways and Means Committee, he was an early advocate and, then, sponsor of the successful repeal in 2000 of the earnings limit for Social Security recipients. He proposed the Good Samaritan Tax Act to permit corporations to take a tax deduction for charitable giving of food. He chairs the Subcommittee on Employer-Employee Relations, where he has encouraged small business owners to expand their pension and benefits for employees. Johnson is a skeptic of calls for increased government regulation related to global warming whenever such government interference would, in his mind, restrict personal liberties or damage economic growth and American competitiveness in the market place. He also opposes calls for government intervention in the name of energy reform if such reform would hamper the market and or place undue burdens on individuals seeking to earn decent wages. He has expressed his belief that the Earth has untapped sources of fuel, and has called for allowing additional drilling for oil in Alaska. Johnson is one of two Vietnam-era POWs still serving in Congress.

Johnson is married to the former Shirley L. Melton, of Dallas. They are parents of three children and ten grandchildren.

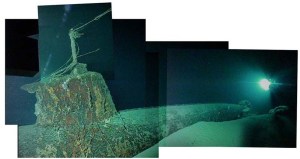

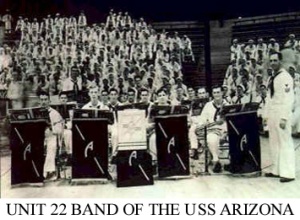

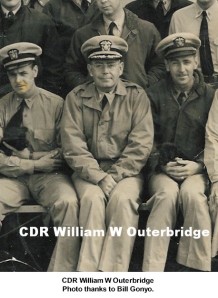

beginning of World War II, Captain William Outerbridge skippered the USS Ward, a re-commissioned ship built during the World War I period. Reportedly in his first command and on his first patrol off Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, Outerbridge

beginning of World War II, Captain William Outerbridge skippered the USS Ward, a re-commissioned ship built during the World War I period. Reportedly in his first command and on his first patrol off Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, Outerbridge and the USS Ward detected a Japanese two-man midget submarine near the entrance to Pearl Harbor. The USS Ward detected the midget sub at 6:45 AM and sank it at 6:54 AM, firing the first shots in defense of the U.S. in World War II. Captain Outerbridge was reportedly awarded the Navy Cross for Heroism.

and the USS Ward detected a Japanese two-man midget submarine near the entrance to Pearl Harbor. The USS Ward detected the midget sub at 6:45 AM and sank it at 6:54 AM, firing the first shots in defense of the U.S. in World War II. Captain Outerbridge was reportedly awarded the Navy Cross for Heroism.

Recent Comments