Category Archives: United States Constitution

Thomas Mifflin – Signer of the United States Constitution – Pennsylvannia

Thomas Mifflin was born January 10, 1744 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, son of John Mifflin and Elizabeth Bagnall. He graduated from the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania) in 1760, and joined the mercantile business of William Biddle. After returning from a trip to Europe in 1765, he established a commercial business partnership with his brother, George Mifflin, and married his distant cousin, Sarah Morris, on March 4, 1765, and the young couple witty, intelligent, and wealthy soon became an ornament in Philadelphia’s highest social circles. In 1768 Mifflin joined the American Philosophical Society, serving for two years as its secretary. Membership in other fraternal and charitable organizations soon followed. Associations formed in this manner quickly brought young Mifflin to the attention of Pennsylvania’s most important politicians, and led to his first venture into politics. In 1771 he won election as a city warden, and a year later he began the first of four consecutive terms in the colonial legislature.

Thomas Mifflin was born January 10, 1744 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, son of John Mifflin and Elizabeth Bagnall. He graduated from the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania) in 1760, and joined the mercantile business of William Biddle. After returning from a trip to Europe in 1765, he established a commercial business partnership with his brother, George Mifflin, and married his distant cousin, Sarah Morris, on March 4, 1765, and the young couple witty, intelligent, and wealthy soon became an ornament in Philadelphia’s highest social circles. In 1768 Mifflin joined the American Philosophical Society, serving for two years as its secretary. Membership in other fraternal and charitable organizations soon followed. Associations formed in this manner quickly brought young Mifflin to the attention of Pennsylvania’s most important politicians, and led to his first venture into politics. In 1771 he won election as a city warden, and a year later he began the first of four consecutive terms in the colonial legislature.

Thomas Mifflin, who represented Pennsylvania at the Constitutional Convention, seemed full of contradictions. Although he chose to become a businessman and twice served as the chief logistical officer of the Revolutionary armies, he never mastered his personal finances. Early in the Revolutionary War, Mifflin left the Continental Congress to serve in the Continental Army. Although his family had been Quakers for four generations, he was expelled from the Religious Society of Friends because his involvement with a military force contradicted his faith’s pacifistic nature. Despite his generally judicious deportment, contemporaries noted his “warm temperament” that led to frequent quarrels, including one with George Washington that had national consequences.

Throughout the twists and turns of a checkered career Mifflin remained true to ideas formulated in his youth. Believing mankind an imperfect species composed of weak and selfish individuals, he placed his trust on the collective judgment of the citizenry. As he noted in his schoolbooks, “There can be no Right to Power, except what is either founded upon, or speedily obtains the hearty Consent of the Body of the People.” Mifflin’s service during the Revolution, in the Constitutional Convention, and, more importantly, as governor during the time when the federal partnership between the states and the national government was being worked out can only be understood in the context of his commitment to these basic principles and his impatience with those who failed to live up to them.

Mifflin’s business experiences colored his political ideas. He was particularly concerned with Parliament’s taxation policy and as early as 1765 was speaking out against London’s attempt to levy taxes on the colonies. A summer vacation in New England in 1773 brought him in contact with Samuel Adams and other Patriot leaders in Massachusetts, who channeled his thoughts toward open resistance. Parliament’s passage of the Coercive Acts in 1774, designed to punish Boston’s merchant community for the Tea Party, provoked a storm of protest in Philadelphia. Merchants as well as the common workers who depended on the port’s trade for their jobs recognized that punitive acts against one city could be repeated against another. Mifflin helped to organize the town meetings that led to a call for a conference of all the colonies to prepare a unified position.

In the summer of 1774 Mifflin was elected by the legislature to the First Continental Congress. There, his work in the committee that drafted the Continental Association, an organized boycott of English goods adopted by Congress, spread his reputation across America. It also led to his election to the Second Continental Congress, which convened in Philadelphia in the aftermath of the fighting at Lexington and Concord.

Mifflin was prepared to defend his views under arms, and he played a major role in the creation of Philadelphia’s military forces. Since the colony lacked a militia, its Patriots turned to volunteers. John Dickinson and Mifflin resurrected the so-called Associators’ (a volunteer force in the colonial wars, perpetuated by today’s 111th Infantry, Pennsylvania Army National Guard). Despite a lack of previous military experience, Mifflin was elected senior major in the city’s 3rd Battalion.

Mifflin’s service in the Second Continental Congress proved short-lived. When Congress created the Continental Army as the national armed force on 14 June 1775, he resigned, along with George Washington, Philip Schuyler, and others, to go on active duty with the regulars. Washington, the Commander-in-Chief, selected Mifflin, now a major, to serve as one of his aides, but Mifflin’s talents and mercantile background led almost immediately to a more challenging assignment. In August, Washington appointed him Quartermaster General of the Continental Army. Washington believed that Mifflin’s personal integrity would protect the Army from the fraud and corruption that too often characterized eighteenth-century procurement efforts. Mifflin, in fact, never used his position for personal profit, but rather struggled to eliminate those abuses that did exist in the supply system.

As the Army grew, so did Mifflin’s responsibilities. He arranged the transportation required to place heavy artillery on Dorchester Heights, a tactical move that ended the siege of Boston. He also managed the complex logistics of moving troops to meet a British thrust at New York City. Promoted to brigadier general in recognition of his service, Mifflin nevertheless increasingly longed for a field command. In 1776 he persuaded Washington and Congress to transfer him to the infantry. Mifflin led a brigade of Pennsylvania Continentals during the early part of the New York City campaign, covering Washington’s difficult nighttime evacuation of Brooklyn. Troubles in the Quartermaster’s Department demanded his return to his old assignment shortly afterwards, a move which bitterly disappointed him. He also brooded over Nathanael Greene’s emergence as Washington’s principal adviser, a role which Mifflin coveted.

Mifflin’s last military action came during the Trenton-Princeton campaign. As the Army’s position in northern New Jersey started to crumble in late November 1776, Washington sent him to Philadelphia to lay the groundwork for a restoration of American fortunes. Mifflin played a vital, though often overlooked, role in mobilizing the Associators to reinforce the Continentals and in orchestrating the complex resupply of the tattered American forces once they reached safety on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River. These measures gave Washington the resources to counterattack. Mifflin saw action with the Associators at Princeton. His service in the campaign resulted in his promotion to major-general.

Mifflin tried to cope with the massive logistical workload caused by Congress’ decision in 1777 to expand the Continental Army. Congress also approved a new organization of the Quartermaster’s Department, but Mifflin had not fully implemented the reforms and changes before Philadelphia fell. Dispirited by the loss of his home and suffering from poor health, Mifflin now attempted to resign. He also openly criticized Greene’s advice to Washington. These ill-timed actions created a perception among the staff at Valley Forge that Mifflin was no longer loyal to Washington.

The feuding among Washington’s staff and a debate in Congress over war policy led to the so-called Conway Cabal. A strong faction in Congress insisted that success in the Revolution could come only through heavy reliance on the militia. Washington and most of the Army’s leaders believed that victory depended on perfecting the training and organization of the Continentals so that they could best the British at traditional European warfare. This debate came to a head during the winter of 1777-78, and centered around the reorganization of the Board of War, Congress’ administrative arm for dealing with the Army. Mifflin was appointed to the Board because of his technical expertise, but his political ties embroiled him in an unsuccessful effort to use the Board to dismiss Washington. This incident ended Mifflin’s influence in military affairs and brought about his own resignation in 1779.

Mifflin lost little time in resuming his political career. While still on active duty in late 1778 he won reelection to the state legislature. In 1780 Pennsylvania again sent him to the Continental Congress, and that body elected him its president in 1783. In an ironic moment, “President” Mifflin accepted Washington’s formal resignation as Commander-in-Chief. He also presided over the ratification of the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolution. Mifflin returned to the state legislature in 1784, where he served as speaker. In 1788 he began the first of two one-year terms as Pennsylvania’s president of council, or governor.

Although Mifflin’s fundamental view of government changed little during these years of intense political activity, his war experiences made him more sensitive to the need for order and control. As Quartermaster General, he had witnessed firsthand the weakness of Congress in dealing with feuding state governments over vitally needed supplies, and he concluded that it was impractical to try to govern through a loose confederation. Pennsylvania’s constitution, adopted in 1776, very narrowly defined the powers conceded to Congress, and during the next decade Mifflin emerged as one of the leaders calling for changes in those limitations in order to strike a balanced apportionment of political power between the states and the national government.

Such a system was clearly impossible under the Articles of Confederation, and Mifflin had the opportunity to press his arguments when he represented Pennsylvania at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Although his dedication to Federalist principles never wavered during the deliberations in Philadelphia, his greatest service to the Constitution came later when, as the nationalists’ primary tactician, he helped convince his fellow Pennsylvanians to ratify it.

Elected governor under the new state constitution in 1790, Mifflin served for nine years, a period highlighted by his constant effort to minimize partisan politics in order to build a consensus. Although disagreeing with the federal government’s position on several issues, Mifflin fully supported Washington’s efforts to maintain the national government’s primacy. He used militia, for example, to control French privateers who were trying to use Philadelphia as a base in violation of American neutrality. He also commanded Pennsylvania’s contingent called out in 1794 to deal with the so-called Whiskey Rebellion, even though he was in sympathy with the economic plight of the aroused western farmers.

In these incidents Mifflin regarded the principle of the common good as more important than transitory issues or local concerns. This same sense of nationalism led him to urge the national government to adopt policies designed to strengthen the country both economically and politically. He led a drive for internal improvements to open the west to eastern ports. He prodded the government to promote “National felicity and opulence … by encouraging industry, disseminating knowledge, and raising our social compact upon the permanent foundations of liberty and virtue.” In his own state he devised a financial system to fund such programs. He also took very seriously his role as commander of the state militia, devoting considerable time to its training so that it would be able to reinforce the Regular Army.

Mifflin retired in 1799, his health debilitated and his personal finances in disarray. In a gesture both apt and kind, the commander of the Philadelphia militia (perpetuated by today’s 111th Infantry and 103rd Engineer Battalion, Pennsylvania Army National Guard) resigned so that the new governor might commission Mifflin as the major-general commanding the states senior contingent. Voters also returned him one more time to the state legislature. He died on 23 January 1800 during the session and was buried (at state expense, since his estate was too small to cover funeral costs,) at Trinity Lutheran Church Cemetery, Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

2nd Amendment

Constitution Lesson #2 – I feel that there is no room for interpretation on this. The reason this amendment was put in the Constitution was so that the people would be equally armed and capable of throwing off the shackles of a tyrannical government if it ever came to that again. For those that argue that we do not need firearms available, try using an M-16 A2 against a Tank. We are already out gunned and the underdog. If you have any opinion that there should be more gun control and bans than there already are, then you probably do not belong in America. It is very cut and dry. Read, study, discuss, and ask questions.

Constitution Lesson #2 – I feel that there is no room for interpretation on this. The reason this amendment was put in the Constitution was so that the people would be equally armed and capable of throwing off the shackles of a tyrannical government if it ever came to that again. For those that argue that we do not need firearms available, try using an M-16 A2 against a Tank. We are already out gunned and the underdog. If you have any opinion that there should be more gun control and bans than there already are, then you probably do not belong in America. It is very cut and dry. Read, study, discuss, and ask questions.

SECOND AMENDMENT OF THE CONSTITUTION

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

Shall not be infringed. So it’s stops there. It’s unconstitutional to even have to get a firearm ID card, permits, and registration for the firearm

Shall not be infringed! Enough said!

So with ‘them’ wanting to twist in laws of regulations on our purchases, do we stick solely to gun shows and private sales for guns and ammo? I mean, that would be the best option right?

As of right now, that does seem like the best option for many. Again, it is the same as the First Amendment; it really depends on what state you live in anymore. The more the government knows about you, the more they can use against you. No sense in giving them more intelligence that isn’t necessary. I could understand why someone would not want “them” knowing you purchased a firearm.

I still can’t get over the fact that when this was written other than a few cannon some may have had the use of that the actual arms were exactly the same yet some ill informed people think that we should only have muskets. This document is not frozen in time it evolves with the world. If the first amendment covers current communication why can’t they see the second covers current arms?

We have guns registered by state. The others were private sale. But now I even wonder about the ammo I just bought last week at a store. I mean, what else have ‘they’ been monitoring besides our emails and phone calls? Start making your own ammo. Reloading is a useful skill to take up.

Some of the liberals have their heads buried so far up their butt that they actually think the 2nd amendment was created for hunting and recreation.

“Shall not be infringed” says it all. But it also talks about a well regulated militia. And I think that’s a very important part. Together we are stronger.

The discipline and regulation of said militia is important so that you do not have a bunch of disorganized idiots running around trying to play Rambo.

“A well regulated militia…” The army national guard? Or private militias? Which would that apply to?

Private. Thought so. I thought that was private such as the minutemen.

Private; meaning the individual citizen, meaning all of us who individually elect to do so.

Wouldn’t it stand for both as a militia consists of 2 parts, organized (state guards) and unorganized (private militias consisting of every able bodied citizen)?

Having a firearm is not about fighting police or government agents. Having a firearm represents that you are prepared for the absolute worst, heaven forbid. Nobody thinks they are going to stop tanks with an AR. The original purposes of the rifle were for competition shooting, and varmint hunting. I think blaming responsible gun owners is absolute nonsense. I don’t know a single gun owner who would willingly supply arms to a criminal or felon, for any amount. The very nature of half of the gun control arguments derive from fear and ignorance of a craft, hobby and a divine right. Not divine from God, but from Nature. You have the right to defend yourself, and we all know there are awful excuses for human beings on this planet. Every time I turn the news on, or log into Facebook, a girl got raped, a couple got murdered, and we’re on the brink of another war. Enough already. Stop demonizing good, law abiding people. We get it. Stop hurting the working class, and stop demonizing innocent people.

It encourages all citizens to be soldiers so to speak. Well armed to defend freedom, more on a domestic level.

It is so cut and dry that the only point that was possibly discussable was the private militia, and that was short lived. It’s simple and profound.

As is the whole Constitution. It is on two pages for the Constitution and one page for the Declaration of Independence so that it would be short, to the point, and easily interpreted. Very different from today’s legislative/Congressional bills.

A private militia can be commanded by an ex or retired Officer of the US Armed Forces.

Go and by a fresh replica today of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights today. Look at them, and be amazed by the fact they were only 2 pieces of parchment!

Simple yet priceless words.

Militias are perfectly legal. They have to be known to the government, but they are legal. There are many, and at least one in every state.

That is if you want to do it the law way, which is a good idea, or they can shut you down in a hurry, technically.

Many people I know of are part of the state militia but also do “activities” in smaller groups. Squad size, if you will.

The bad thing is that the left wing media has painted a bad picture for militias even though they have not been in a terrorist attack.

Here’s the thing with the militia. You run around calling yourself a MILITIA, and people automatically think NUT JOB. We don’t need this. Instead of running around like idiots, in surplus army gear, just practice shooting with your buddies at a range. The left wing media make militias look like neo Nazi and crazy hillbillies.

Shall not be infringed . . . there is nothing more to be said . . . no one has the authority to take away something God has given.

This is the sad part . . . how can someone paint something as “terroristic” that is perfectly legal according to the United States Constitution?

People pin Patriots in a bad light to convince the weak that “Patriots” are bad and the government is justified for taking our rights away.

The only good thing about the Left is that they make themselves look like total idiots multiple times on a daily basis. What people forget is that liberal sentiment resides on the coasts, but inland, central, northern, and southern parts of the United States are a different world. This is still a 50/50 fight at the least. Sure, liberals control the media, but we are fixing that. Gun owners, both Red and Blue States, are telling the current regime no way their gun control agenda will work and it is falling apart.

“Shall not be fringed upon”. Enough said!

The Second Amendment says ‘the right of the people’, it does not say it is a privilege; and that RIGHT SHALL NOT be infringed. We know that felons are not allowed firearms. It does not pertain to misdemeanercrime too. My question is this. Are the rights of those felons regardless if it’s a violent crime or not, are their rights being infringed upon? I’ve heard said that gun ownership is a privilege not a right. That rights can’t be taken but privilege can. I do know of rights that are trampled on every day. I wonder also if background checks then infringe. The point of a background check would be for them to prepare to infringe.

Insulting Militia is not going to get us anywhere when many people on here are in and support militias. It is a right protected by the Constitution to form militias. I agree that it needs to be organized, but as was stated by the boss earlier, in fighting isn’t going to be tolerated.

But you don’t just have to be a felon domestic dispute will get them taken as well regardless. Form a hunting club, or a marksmanship team. Network with police officers, and sheriff’s deputies whenever possible. Get in good with your neighbors. Practice your sport. Get proficient. This should be your new craft or hobby on the same level of “Bowling, Softball, Volleyball, Flag Football,” or whatever you used to occupy your time with.

When the law was written, most felons would have seen the gallows. No reason to restrict their firearm ownership. Take their lives. They don’t sit on death row clogging up the legal system with endless appeals. Background checks, waiting periods and limits on types and modifications are ALL ways of infringing on our God-given right to protect ourselves from a government that’s gotten too big for its breeches. I’m a firm believer that if you can afford to buy a weapon that’s very much a military weapon, like an M134 Dillon Minigun or an M1 Abrams tank and it’s various ammunition and armament, you should be allowed to.

Host shooting competitions. For the love of god, Develop Rifle Competency!

The first ‘assault rife’- the lever-action repeating rifle, was immediately available to any civilian that had the money to purchase one . . . of course when the second amendment was penned private citizens owned cannon, mortars and naval warships, there was no discussion at that time about limiting possession of ‘arms’ based on their type . . . if you had the money you could own whatever you wanted we’ve gotten very far away from what was intended when the amendment was written . . . for the most part because the elected elite are scarred to death that WE THE PEOPLE might actually remember why that right is enumerated and might actually exercise it in for its intended purpose . . .

THE RIGHT OF THE PEOPLE . . . Shall NOT BE INFRINGED . . . In Simple English . . . Any Questions?

Whoever controls the money and the weapons, has the power . . . That’s what they want . . . And the social media and news media promote it . . . They hope we are too busy playing and not watching . . . .

This amendment is so simple, it raises too many questions. No wonder it’s so difficult for a liberal to understand.

It is well put. It is difficult to have a discussion with people that an automatic firearm should be legal.

“Shall not be infringed ” doesn’t get any more clear than that!!!

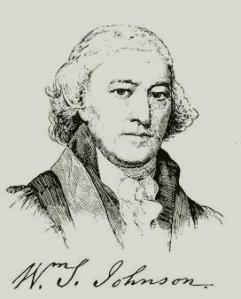

William Samuel Johnson – Signer of the United States Constitution – Connecticut

William Samuel Johnson was one of the best educated of the Founding Fathers. His knowledge of the law led him to oppose taxation without representation as a violation of the colonists’ rights as Englishmen, but his strong ties with Great Britain made renunciation of the King personally reprehensible. Torn by conflicting loyalties, he remained neutral during the Revolution, speaking out only against extremism on both sides. Once George III accepted American independence, however, Johnson felt released from his allegiance and readily committed his considerable intellectual abilities to the strengthening of the new nation. Fellow delegate William Pierce said of him, “Johnson possesses the manners of a Gentleman and engages the Hearts of Men by the sweetness of his temper, and that affectionate style of address with which he accosts his acquaintance …. eloquent and clear, always abounding with information and instruction, . . . [He is] one of the first classics in America.”

William Samuel Johnson was one of the best educated of the Founding Fathers. His knowledge of the law led him to oppose taxation without representation as a violation of the colonists’ rights as Englishmen, but his strong ties with Great Britain made renunciation of the King personally reprehensible. Torn by conflicting loyalties, he remained neutral during the Revolution, speaking out only against extremism on both sides. Once George III accepted American independence, however, Johnson felt released from his allegiance and readily committed his considerable intellectual abilities to the strengthening of the new nation. Fellow delegate William Pierce said of him, “Johnson possesses the manners of a Gentleman and engages the Hearts of Men by the sweetness of his temper, and that affectionate style of address with which he accosts his acquaintance …. eloquent and clear, always abounding with information and instruction, . . . [He is] one of the first classics in America.”

Johnson was already a prominent figure before the Revolution. The son of a well-known Anglican clergyman and later president of King’s (Columbia) College, Johnson received his primary education at home. He then graduated from Yale College in 1744, going on to receive a master’s degree from his alma mater in 1747 (as well as an honorary degree from Harvard the same year). Although his father urged him to enter the clergy, Johnson decided instead to pursue a legal career. Self-educated in the law, he quickly developed an important clientele and established business connections extending beyond the boundaries of his native colony. He also held a commission in the Connecticut colonial militia for over 20 years, rising to the rank of colonel, and he served in the lower house of the Connecticut legislature (1761 and 1765) and in the upper house (1766 and 1771-75). He was a member as well of the colony’s supreme court (1772-74).

Johnson was first attracted to the Patriot cause by what he and his associates considered Parliament’s unwarranted interference in the government of the colonies. He attended the Stamp Act Congress in 1765 and served on the committee that drafted an address to the King arguing the right of the colonies to decide tax policies for themselves. He opposed the Townshend Acts passed by Parliament in 1767 to pay for the French and Indian War and supported the non-importation agreements devised by the colonies to protest taxation without representation.

As the Patriots became more radical in their demands for independence, Johnson found it difficult to commit himself wholeheartedly to the cause. Although he believed British policy unwise, he found it difficult to break his own connections with the mother country. A scholar of international renown, he had many friends in Britain and among the American Loyalists. As the famous English author, Samuel Johnson, said of him, “Of all those whom the various accidents of life have brought within my notice, there is scarce anyone whose acquaintance I have more desired to cultivate than yours.” He was also bound to Britain by religious and professional ties. He enjoyed close associations with the Anglican Church in England and with the scholarly community at Oxford, which awarded him an honorary degree in 1766. He lived in London from 1767 to 1771, serving as Connecticut’s agent in its attempt to settle the colony’s title to Indian lands.

Fearing the consequences of independence for both the colonies and the mother country, Johnson sought to avoid extremism and to reach a compromise on the outstanding political differences between the protagonists. He rejected his election to the First Continental Congress, a move strongly criticized by the Patriots, who removed him from his militia command. He was also strongly criticized when, seeking an end to the fighting after Lexington and Concord, he personally visited the British commander, General Thomas Gage. The incident led to his arrest for communicating with the enemy, but the charges were eventually dropped.

Johnson’s pro-peace activities apparently never seriously damaged his prestige. He served as a legal counsel for Connecticut in its dispute with Pennsylvania over western lands (1779-80) and was nominated by Joseph Reed, president of the College of Philadelphia (later the University of Pennsylvania), to succeed him as head of the college.

Once independence was achieved, Johnson felt free to participate in the government of the new nation, serving in the Continental Congress (1785-87). His influence as a delegate was recognized by his contemporaries. Jeremiah Wadsworth wrote of him to a friend, “Dr. Johnson has, I believe, much more influence than either you or myself. The Southern Delegates are vastly fond of him.”

Johnson played a major role as one of the Convention’s most important and respected delegates. His eloquent speeches on the subject of representation carried great weight during the debate. He looked to a strong federal government to protect the rights of Connecticut and the other small states from encroachment by their more powerful neighbors. To that end he supported the so-called New Jersey Plan, which called for equal representation of the states in the national legislature.

In general, he favored extension of federal authority. He argued that the judicial power “ought to extend to equity as well as law” (the words “in law and equity” were adopted at his motion) or, in other words, that the inflexibility of the law had to be tempered by fairness. He denied that there could be treason against a separate state since sovereignty was “in the Union;” and he opposed prohibition of any ex post facto law, one which made an act a criminal offense retroactively, because such prohibition implied “an improper suspicion of the National Legislature.”

Johnson was influential even in the final stages of framing the Constitution. He gave his fullest support to the Connecticut Compromise, which foreshadowed the final Great Compromise that devised a national legislature with a Senate that provided equal representation for all states and a House of Representatives based on population. He also served on the Committee of Style, which framed the final form of the document.

Johnson played an active role in Connecticut’s ratification process, emphasizing the advantages that would accrue to the small states under the Constitution. He was especially proud of the document’s legal clauses, in which “the force, which is to be employed, is the energy of Law; and this force is to operate only on individuals, who fail in their duty to their country.”

As one of Connecticut’s first senators (1789-91), Johnson took an active part in shaping the Judiciary Act of 1789, a critical law that established the details of the federal judiciary system. He also supported Hamiltonian measures that sought to strengthen the role of the executive in the federal government, but voted against giving the President the power to remove cabinet officers without senatorial approval. Johnson had become president of Columbia College in 1787, and when the federal government moved from New York to Philadelphia at the end of the First Congress, he retired from public office to retain his position at the school.

As president of Columbia to 1800, Johnson recruited faculty members and established the school on a firm financial basis. While maintaining the school’s strongly religious spirit, he did much to improve its prestige and reputation for scholarship. As a prominent Anglican layman, he also helped reorganize the church under a new, American episcopate.

He was born on 7 October 1727, in Stratford, Connecticut and passed on 14 November 1819, in Stratford, Connecticut. He is buried in the Old Episcopal Cemetery in Stratford, Connecticut.

Richard Bassett – Signer of the United States Constitution – Delaware

Richard Bassett was born at Bohemia Ferry in the Province of Maryland’s Cecil County. His mother, Judith Thompson, had married part-time tavern-owner and farmer Michael Bassett who deserted the family during Richard’s childhood. Since Judith Thompson was the great-granddaughter and heiress of Augustine Herrman, the original owner of Cecil County’s massive estate of Bohemia Manor, her family raised young Richard. Eventually this heritage provided him with inherited wealth, including the Bohemia Manor plantation as well as much other property in Delaware’s New Castle County.

Richard Bassett was born at Bohemia Ferry in the Province of Maryland’s Cecil County. His mother, Judith Thompson, had married part-time tavern-owner and farmer Michael Bassett who deserted the family during Richard’s childhood. Since Judith Thompson was the great-granddaughter and heiress of Augustine Herrman, the original owner of Cecil County’s massive estate of Bohemia Manor, her family raised young Richard. Eventually this heritage provided him with inherited wealth, including the Bohemia Manor plantation as well as much other property in Delaware’s New Castle County.

Bassett studied law under Judge Robert Goldsborough of Province of Maryland’s Dorchester County and, in 1770, was admitted to the Bar. He moved to Delaware and began a practice in Kent County’s court town of Dover, which, in 1777, became the newly independent state’s capital city. By concentrating on agricultural pursuits as well as religious and charitable concerns, he quickly established himself amongst the local gentry and “developed a reputation for hospitality and philanthropy.” In 1774, at the age of 29, Richard married Ann Ennals and they had three children, Richard Ennals, Ann (known as Nancy) and Mary. After Ann Ennals’ death he married Betsy Garnett in 1796. They were active members of the Methodist Church, and gave the church much of their time and attention.

Bassett was a reluctant revolutionary, more closely in tune with the approach of George Read than with his neighbors from Kent County, Caesar Rodney and John Haslet. Nevertheless, in 1774 he was elected to the local Boston Relief Committee. When the new government of Delaware was organized, Bassett served on the 1776 Delaware Council of Safety, and was a member of the convention responsible for drafting the Delaware Constitution of 1776, which was adopted September 20, 1776. He was then one of the conservatives elected to 1st Delaware General Assembly, and served for four sessions, from 1776-80. Subsequently, he was a member of the House of Assembly for the 1780-82 sessions, and returned to the Legislative Council, for three sessions from 1782-85. He concluded his state legislative career with a final term in the House of Assembly during the 1786-87 session. He thereby represented Kent County in all but one session of the Delaware General Assembly from independence to the adoption of the U.S. Constitution of 1787.

However, Bassett’s most notable contributions during the American Revolution were his efforts to mobilize the state’s military. Some sources credit him with developing the plans for raising and staffing the 1st Delaware Regiment, with his neighbor, John Haslet at its command. Known as the “Delaware Continentals” or “Delaware Blues”, they were from the smallest state, but at some 800 men, were the largest battalion in the Continental Army. In 1776, historian David McCullough describes them as “turned out in handsome red trimmed blue coats, white waistcoats, buckskin breeches, white woolen stockings, and carrying fine, ‘lately imported’ English muskets”. Raised in early 1776, they went into service in July and August 1776. Bassett also participated in the recruitment of the reserve militia that served in the “Flying Camp” of 1776, and the Dover Light Infantry, led by another neighbor, Thomas Rodney.

When the British Army marched through northern New Castle County, on the way to the Battle of Brandywine and the capture of Philadelphia, Bassett “appears to have joined his friend Rodney in the field as a volunteer”. Once the Delaware militia returned home after the British retired from the area, Bassett continued as a part-time soldier, assuming command of the Dover Light Horse, Kent County’s militia cavalry unit. In 1799 Bassett was elected governor of Delaware and held his position until 1801.

Bassett was one of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention and, without supplying much input, signed the Constitution. Meanwhile, the Delaware Constitution of 1776 was in need of revision, and Bassett once again joined with another of Delaware’s Founding Fathers, John Dickinson in leading the convention to draft a revision, which became the Delaware Constitution of 1792. Upon his retirement from the United States Senate in 1793, Bassett began a six-year term as the first Chief Justice of the Delaware Court of Common Pleas. At the time it was a court of general civil jurisdiction and the predecessor of the present Delaware Superior Court. By this time Bassett was formally a member of the Federalist Party, and as such was elected Governor of Delaware in 1799. It was during his time in office that Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours first came to Delaware to begin his gunpowder business.

It was also during his term as governor that Thomas Jefferson was elected President of the United States, causing great concern for the future of the country among the Federalists. The retiring President John Adams, rushed the Judiciary Act of 1801 through the Federalist 6th Congress, creating a number of new judgeships on the United States circuit courts. Being a staunch Federalist and old political ally, Adams, on his last day in office, February 18, 1801, appointed Bassett, as part of the so-called “midnight judge” appointments, to one of the positions, judge of the Third Circuit. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on February 20, 1801, and received his commission the same day. But the legislation was repealed by the new Jeffersonian 7th Congress, and his tenure ended quickly on July 1, 1802. He never again held public office.

In addition to his high-profile in government, Bassett was a devout and energetic convert to Methodism. Having met Francis Asbury in 1778 at the home of their mutual friend, Judge Thomas White, Bassett soon had a conversion experience, and for the remainder of his life devoted much of his attention and wealth to the promotion of Methodism. He and Asbury remained lifelong friends. This association caused him to become linked in many people’s minds to the loyalists, as both White and Asbury were viewed to be opposed to the war. But it also led to a strong abolitionist belief, which led him to free his own slaves and advocate the emancipation of others.

Bassett died at Bohemia Manor and was first buried there. In 1865 his remains were moved to a Bassett and Bayard mausoleum in the Wilmington and Brandywine Cemetery in Delaware’s largest city, Wilmington.

Abraham Baldwin – Signer of the United States Constitution – Georgia

Abraham Baldwin, was born on November 22, 1754, to Lucy Dudley and Michael Baldwin in North Guilford, Connecticut. He represented Georgia at the Constitutional Convention. Baldwin was a fervent missionary of public education. Throughout his career he combined a faith in democratic institutions with a belief that an informed citizenry was essential to the continuing wellbeing of those institutions. The son of an unlettered Connecticut blacksmith, Baldwin through distinguished public service clearly demonstrated how academic achievement could open opportunities in early American society. Educated primarily for a position in the church, he served in the Continental Army during the climactic years of the Revolution. There, close contact with men of widely varying economic and social backgrounds broadened his outlook and experience and convinced him that public leadership in America included a duty to instill in the electorate the tenets of civic responsibility.

Abraham Baldwin, was born on November 22, 1754, to Lucy Dudley and Michael Baldwin in North Guilford, Connecticut. He represented Georgia at the Constitutional Convention. Baldwin was a fervent missionary of public education. Throughout his career he combined a faith in democratic institutions with a belief that an informed citizenry was essential to the continuing wellbeing of those institutions. The son of an unlettered Connecticut blacksmith, Baldwin through distinguished public service clearly demonstrated how academic achievement could open opportunities in early American society. Educated primarily for a position in the church, he served in the Continental Army during the climactic years of the Revolution. There, close contact with men of widely varying economic and social backgrounds broadened his outlook and experience and convinced him that public leadership in America included a duty to instill in the electorate the tenets of civic responsibility.

Baldwin also displayed a strong sense of nationalism. Experiences during the war as well as his subsequent work in public education convinced him that the future well-being of an older, more prosperous state like Connecticut was closely linked to developments in newer frontier states like Georgia, where political institutions were largely unformed and provisions for education remained primitive. His later political career was animated by the conviction that only a strong central government dedicated to promoting the welfare of the citizens of all the states could guarantee the fulfillment of the ideals and promises of the Revolution.

The Baldwins were numbered among the earliest New England settlers. Arriving in Connecticut in 1639, the family produced succeeding generations of hard-working farmers, small-town tradesmen, and minor government officials. Abraham Baldwin’s father plied his trade in Guilford, Connecticut. Abraham eventually rose to the rank of lieutenant in the local unit of the Connecticut militia. A resourceful man with an overriding faith in the advantages of higher education, he moved his family to New Haven where he borrowed heavily to finance his sons’ attendance at Yale College (now Yale University). Abraham Baldwin never married, but he made a similar sacrifice, for after his father’s death he assumed many family debts and personally financed the education of the family’s next generation.

Baldwin graduated from Yale in 1772, but, intending to become a Congregationalist minister, he remained at the school as a graduate student studying theology. In 1775 he received a license to preach, but he decided to defer full-time clerical duties in order to accept a position as tutor at his alma mater. For the next three years he continued in this dual capacity, becoming increasingly well-known both for his piety and modesty and for his skill as an educator with a special knack for directing and motivating the young men of the college.

Baldwin’s continuing association with Yale College contributed directly to his entry into military service. The college, which had produced a major share of Connecticut’s clergy for nearly a century, now became the major source of chaplains for the states Continental Army contingent. Baldwin apparently served as a chaplain with Connecticut forces on a part-time basis during the early stages of the war, and finally in February 1779 he succeeded the Reverend Timothy Dwight, another Yale tutor, as one of the two brigade chaplains allotted to Connecticut’s forces. He was appointed as chaplain in Brigadier General Samuel H. Parsons’ brigade, remaining with the unit until the general demobilization of the Army that followed the announcement of the preliminary treaty of peace in June 1783.

The duties of a Revolutionary War chaplain were quite extensive, varying considerably from the modern concept of a clergyman’s military role. In addition to caring for the spiritual needs of the 1,500 or so soldiers of differing denominations in the brigade, Baldwin assumed a major responsibility for maintaining the morale of the men and for guarding their physical welfare. He was also assigned certain educational duties, serving as a political adviser to the brigade commander and subordinate regimental commanders. In his sermons and in less formal conversations with the officers and men he was expected to help the soldiers understand the basis for the conflict with the mother country and thereby to heighten their sense of mission and dedication to the Patriot cause.

Although Baldwin’s unit did not participate in combat during the last four years of the war, it still played a major role in Washington’s defensive strategy. The Connecticut brigades were assigned to garrison duty near West Point. There they helped secure vital communications along the Hudson River and guard this critical base area against British invasions. They performed their mission well; the Continental brigades in the Hudson Valley formed the bedrock of Washington’s main army against which no British general was likely to attack. With his center thus secured, Washington was free to launch successful offensive operations against smaller enemy forces in other parts of the country. The soldiers in Baldwin’s brigade eventually trained for an amphibious attack on the British stronghold at New York City late in the war, but the plan was never put into effect.

Baldwin had little to do with these purely military matters, but his service as a chaplain proved vital to the Patriot cause. Along with the rest of the main Continental line units from the New England and middle states, Baldwin’s Connecticut brigade had weathered the darkest days of the war. During 1778 these units had received rigorous training under Washington’s famed Inspector General, Frederick von Steuben, and they had emerged as seasoned professionals, the equal of Britain’s famous Redcoats. Nevertheless, the’ deprivations of such a long war exacted a toll on morale, leading to desertions and occasional mutinies in the 1780s. The Connecticut units, however, remained among the most reliable. Thanks in great part to the success of leaders like Baldwin, the troops had been thoroughly educated as to the nation’s war aims and the need for extended service by the Continental units. As a result, Connecticut stood firm.

Military service in turn had a profound influence on Baldwin’s future. During these years he became friends with many of the Continental Army’s senior officers, including Washington and General Nathanael Greene, who would take command in the south in late 1780. He was also a witness to Major General Benedict Arnold’s betrayal of his country. These associations moved the somewhat cloistered New England teacher and theology student toward a broader political outlook and a strong moral commitment to the emerging nation.

In 1783 Baldwin returned to civilian life and to a change in career. He rejected opportunities to serve as a minister and to assume the prestigious post as Yale’s Professor of Divinity. While still in the Army he had studied law and had been admitted to the Connecticut bar. Now, after settling his family’s affairs, he left New England for the frontier regions of Georgia, where he established a legal practice in Wilkes County near Augusta. Two men probably influenced this decision. Nathanael Greene had announced his intention to move to the state he had so recently freed from British occupation and was encouraging other veterans to join him in settling along the frontier. More importantly, Governor Lyman Hall, himself a Yale graduate, was interested in finding a man of letters to assist in developing a comprehensive educational system for Georgia. He apparently asked Yale’s president, Ezra Stiles, to help him in the search, and Baldwin was persuaded to accept the responsibility.

Baldwin decided that the legislature was the proper place in which to formulate plans for the education of Georgia’s citizens. A year after moving to the state, he won a seat in the lower house, one he would continue to hold until 1789. During his first session in office he drew up a comprehensive plan for secondary and higher education in the state that was gradually implemented over succeeding decades. This plan included setting aside land grants to fund the establishment of Franklin College (today’s University of Georgia), which he patterned after Yale.

Baldwin quickly emerged as one of the leaders in the Georgia legislature. In addition to sponsoring his educational initiatives, he served as the chairman of numerous committees and drafted many of the states first laws. His role reflected not only an exceptional political astuteness, but also an ability to deal with a wide variety of men and situations. As the son of a blacksmith, Baldwin exhibited a natural affinity for the rough men of the Georgia frontier; as the graduate of one of the nation’s finest schools, he also related easily to the wealthy and cultured planters of the coast. This dual facility enabled him to mediate differences that arose among the various social and economic groups coalescing in the new state. As a result, he exercised a leadership role in the legislature by devising compromises necessary for the adoption of essential administrative and legal programs.

Baldwin’s exceptional work in the legislative arena prompted political leaders in his adopted state to assign him even greater responsibilities. In early 1785 Georgia elected him to the Continental Congress, initiating a career in national government that would end only with his death. Although he had moved to Georgia to serve as a “missionary in the cause of education:’ as he put it, he nevertheless willingly assumed the burdens associated with national politics in the cause of effective government. In 1787 Georgia called on Baldwin to serve in the Constitutional Convention where, avoiding the limelight, he earned the respect of his colleagues both for his diligence as a delegate and his effectiveness as a compromiser. Baldwin remained active in politics during his years as president of the University of Georgia. He continued to hold his seat in the Georgia Assembly until 1789, but in 1785, he was also elected to the Confederation congress. Two years later, Baldwin served as one of four Georgia delegates to the constitutional convention of 1787 (the other delegates were William Few Jr., William Houston, and William Pierce. Of the Georgia delegates, only Baldwin and William Few signed the constitution.

Baldwin was an active participant in the deliberations over representation that were at the heart of the constitutional process. He had originally supported the idea of representation in the national legislature based on property qualifications, which he saw as a way to bond together the traditional leadership elements and the new sources of political and economic power. When delegates from his native state convinced him that small states like Connecticut would withdraw from the Convention if the Constitution did not somehow guarantee the equality of state representation, he changed his stand. His action tied the vote on the issue and paved the way for consideration of the question by a committee. Baldwin eventually helped draw up the Great Compromise, whereby a national legislature gave equal voice to all thirteen states in a Senate composed of two representatives from each, but respected the rights of the majority in a House of Representatives based on population. His role in this compromise was widely recognized, and Baldwin himself considered his work in drafting the Constitution as his most important public service.

After the adoption of the Constitution, Baldwin continued to serve in the last days of the old Continental Congress and then went on to serve five terms in the House of Representatives and two terms in the Senate, including one session as the President Pro Tem of that body. His political instincts prompted him to support the more limited nationalist policies associated with James Madison, and he was widely recognized as a leader of the moderate wing of the Democratic-Republican party. Throughout his years of congressional service, Baldwin remained an effective molder of legislative opinion, working in committees as well as in informal political circles to develop the laws that fleshed out the skeletal framework provided by the Constitution.

Baldwin’s political philosophy was encapsulated in his often quoted formula for representative governments: “Take care, hold the wagon back; there is more danger of its running too fast than of its going too slow.” A man of principle, who had learned much from his service in the Continental Army, Baldwin demonstrated throughout a lengthy public career the value of accommodation between competing political interests, the critical need of national unity, and the importance of education to a democratic society.

Baldwin is remembered today in Georgia primarily for his statewide educational program that created a state university and provided state funds for that institution. Highlighting his own education principles, Baldwin once stated that Georgia must “place the youth under the forming hand of Society, that by instruction they may be moulded to the love of Virtue and good Order.” He believed that no republic was secure without a well-informed constituency. Baldwin never married. In a curious parallel to a later renowned Georgian, Alexander Stephens, Baldwin assumed custody of six of his younger half-siblings upon his father’s death and reared, housed, and educated them all at his own expense.

On March 4, 1807, at age fifty-three, Baldwin died while serving as a U.S. senator from Georgia. Later that month the Savannah Republican and Savannah Evening Ledger reprinted a eulogy of the great statesman, which had first appeared in a Washington, D.C., newspaper: “He originated the plan of the University of Georgia, drew up the charter, and with infinite labor and patience, in vanquishing all sorts of prejudices and removing every obstruction, he persuaded the assembly to adopt it.” Baldwin is buried in Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, D.C. Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College in Tifton, Georgia and Baldwin County in middle Georgia are named in his honor.

Daniel Carroll – Signer of the United States Constitution – Maryland

Daniel Carroll was born on 22 July 1730 in Upper Marlboro, Prince Georges County, Maryland, the oldest son of Daniel Carroll, a native of Ireland, and Eleanor Darnall Carroll, of English descent. He spent his early years at his family’s home, a large estate of thousands of acres which his mother had inherited. (Several acres are now associated with the house museum known as Darnall’s Chance, listed on the National Register of Historic Places).

Daniel Carroll was born on 22 July 1730 in Upper Marlboro, Prince Georges County, Maryland, the oldest son of Daniel Carroll, a native of Ireland, and Eleanor Darnall Carroll, of English descent. He spent his early years at his family’s home, a large estate of thousands of acres which his mother had inherited. (Several acres are now associated with the house museum known as Darnall’s Chance, listed on the National Register of Historic Places).

Daniel was sent abroad for his education. Between 1742 and 1748 he studied under the Jesuits at the College of St. Omer in Flanders, established for the education of English Catholics after the Protestant Reformation. Then, after a tour of Europe, he sailed home and soon married Eleanor Carroll, a first cousin of Charles Carroll of Carrollton.

Carroll gradually joined the Patriot cause. A planter, slaveholder and large landholder, he was concerned lest the Revolution fail economically and bring about not only his family’s financial ruin, but mob rule as well.

Carroll, supported the cause of American independence, risking his social and economic position for the Patriot cause. As a friend and staunch ally of George Washington, he worked for a strong central government that could secure the achievements and fulfill the hopes of the Revolution. Carroll fought in the Convention for a government responsible directly to the people of the country.

At the time, colonial laws excluded Catholics from holding public office. Once these laws were nullified by the Maryland constitution of 1776, Carroll was elected to the Senate of the Maryland legislature (1777-81). At the end of his term, Carroll was elected to the Continental Congress (1781-84). In 1781, he signed the Articles of Confederation. His involvement in the Revolution, like that of other Patriots in his extended family, was inspired by the family’s motto: “Strong in Faith and War”.

Carroll was an active member of the Constitutional Convention. Like his good friend James Madison, Carroll was convinced that a strong central government was needed to regulate commerce among the states and with other nations. He also spoke out repeatedly in opposition to the payment of members of the United States Congress by the states, reasoning that such compensation would sabotage the strength of the new government because “…the dependence of both Houses on the state Legislatures would be complete…. The new government in this form is nothing more than a second edition of [the Continental] Congress in two volumes, instead of one, and perhaps with very few amendments.”

At the Constitutional Convention, Daniel Carroll played an essential role in formulating the limitation of the powers of the federal government. He was the author of the presumption – enshrined in the Constitution – that powers not specifically delegated to the federal government were reserved to the states or to the people. Carroll spoke about 20 times during the debates at the Constitutional Convention and served on the Committee on Postponed Matters. Returning to Maryland after the convention, he campaigned for ratification of the Constitution, but was not a delegate to the state convention.

When it was suggested that the President should be elected by the Congress, Carroll, seconded by Wilson, moved that the words “by the legislature” be replaced with “by the people”. He and Thomas Fitzsimons were the only Roman Catholics to sign the Constitution, a symbol of the advance of religious freedom in America during the Revolutionary period.

Following the Convention, Carroll continued to be involved in state and national affairs. He was a key participant in the Maryland ratification struggle. He defended the Constitution in the pages of the Maryland Journal, most notably in his response to the arguments advanced by the well-known Anti-federalist Samuel Chase. After ratification was achieved in Maryland, Carroll was elected as a representative from the sixth district of Maryland to the First Congress. Given his concern for economic and fiscal stability, he voted for the assumption of state debts by the federal government.

One of three commissioners appointed to survey the District of Columbia, Carroll owned one of the four farms taken for it; Notley Young, David Burns, and Samuel Davidson were the other landowners. The capitol was built on the land which Carroll transferred to the government. On 15 April 1791, Carroll and David Stuart, as the official commissioners of Congress, laid the cornerstone of the District of Columbia at Jones Point near Alexandria, Virginia.

He later was elected to the Maryland Senate. He was appointed a commissioner (co-mayor) of the new capital city, but advanced age and failing health forced him to retire in 1795. Interest in his region kept him active. He became one of George Washington’s partners in the Patowmack Company, a business enterprise intended to link the East with the expanding West by means of a Potomac River canal.

Carroll was one of only five men to sign both the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution of the United States.

Daniel Carroll died on 5 July 1796, at the age of 65 at his home near Rock Creek in the present village of Forest Glen, Md. He was buried there in St. John’s Catholic Cemetery.

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney – Signer of the Constitution – South Carolina

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (C.C.), born 25 February 1746, at Charleston, South Carolina, was the son of Charles and Eliza Lucas Pinckney. His cousin, Charles, also a signer of the Constitution, from Charleston, South Carolina, was also from colony of South Carolina. C.C.’s mother Eliza Lucas held a special position as an agriculturist, while his elder brother Thomas Pinckney became the Governor of South Carolina in addition to holding a position in George Washington’s regime as an administration diplomat. C.C. followed in his brother’s footsteps when he later served as an administration diplomat in Thomas Jefferson’s White House and as South Carolina’s Governor.

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (C.C.), born 25 February 1746, at Charleston, South Carolina, was the son of Charles and Eliza Lucas Pinckney. His cousin, Charles, also a signer of the Constitution, from Charleston, South Carolina, was also from colony of South Carolina. C.C.’s mother Eliza Lucas held a special position as an agriculturist, while his elder brother Thomas Pinckney became the Governor of South Carolina in addition to holding a position in George Washington’s regime as an administration diplomat. C.C. followed in his brother’s footsteps when he later served as an administration diplomat in Thomas Jefferson’s White House and as South Carolina’s Governor.

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, was one of the representatives from South Carolina at the Constitutional Convention, an American aristocrat. Like other first families of South Carolina, whose wealth and social prominence could be traced to the seventeenth century, the Pinckneys maintained close ties with the mother country and actively participated in the Royal colonial government. Nevertheless, when armed conflict threatened, he rejected Loyalist appeals and embraced the Patriot cause. Pragmatically, his decision represented an act of allegiance to the mercantile-planter class of South Carolina’s seaboard, which deeply resented Parliament’s attempt to institute political and economic control over the colonies. Yet Pinckney’s choice also had a philosophical dimension. It placed him among a small group of wealthy and powerful southerners whose profound sense of public duty obliged them to risk everything in defense of their state and the rights of its citizens. In Pinckney’s case this sense of public responsibility was intensified by his determination to assume the mantle of political and military leadership traditionally worn by members of his family.

Balancing this allegiance to his native state, Pinckney also became a forceful exponent of nationalism during the Revolutionary War. Unlike many of his contemporaries, who generously responded only when their own states were in danger, Pinckney quickly came to grasp the necessity for military cooperation on a national scale. No state was truly safe, he reasoned, unless all the states were made safe. This belief, the product of his service in the Continental Army, easily translated into a spirited defense of strong national government after the war.

As a boy, Pinckney witnessed firsthand the close relationship between the colonial elite and the British. His father was the colony’s chief justice and also served as a member of its Royal Council; his mother was famous in her own right for introducing the cultivation of indigo, which rapidly became a major cash crop in South Carolina. In 1753 the family moved to London where the elder Pinckney served as the colony’s agent, in effect, as a lobbyist protecting colonial interests in political and commercial matters. C.C. Pinckney enrolled in the famous Westminster preparatory school, and he with his brother Thomas remained in England to complete his education when the family returned to America in 1758. After graduating from Christ Church College at Oxford, he studied law at London’s famous Middle Temple. He was admitted to the English bar in 1769, but he continued his education for another year, studying botany and chemistry in France and briefly attending the famous French military academy at Caen.

Returning to South Carolina after an absence of sixteen years, C.C. quickly threw himself into the commercial and political life of the colony. To supplement an income derived from plantations, he launched a successful career as a lawyer. He became a vestryman and warden in the Episcopal Church and joined the socially elite 1st Regiment of South Carolina militia, which promptly elected him as lieutenant. In 1770 he won a seat for the first time in the state legislature, and in 1773 he served briefly as a regional attorney general. During this period he married Sarah Middleton, the daughter of Henry Middleton. Sarah passed away in 1784 and C.C. remarried Mary Stead two years later.

When war between the colonies and the mother country finally erupted in 1775, C.C. cast aside his close ties with England and South Carolina’s Royal colonial government to stand with the Patriots. He served in the Provincial Congresses that transformed South Carolina from Royal colony to independent state and in the Council of Safety that supervised affairs when the legislature was not in session. During this period C.C. played an especially important role in those legislative committees that organized the state’s military defenses.

Directing the organization of military units from the relative safety of the state legislature did not satisfy C.C.’s sense of public obligation. Going beyond his previous militia service, he now volunteered as a full-time regular officer in the first Continental Army unit organized in South Carolina. As a senior company commander, he raised and led the elite Grenadiers of the 1st South Carolina Regiment. He participated in the successful defense of Charleston in June 1776, when British forces under General Sir Henry Clinton staged an amphibious attack on the state capital. Later in 1776 he took command of the regiment, with the rank of full colonel, a position he retained to the end of the war. A strong disciplinarian, he also understood the importance of troop motivation, especially when his men were forced to serve for long periods under dangerous and stressful conditions.

Following the successful repulse of General Clinton’s forces in 1776, the southern states enjoyed a hiatus in the fighting while the British Army concentrated on operations in the northern and middle states. Dissatisfied with remaining in what had become a backwater of the war, C.C. set out to join Washington near Philadelphia. He arrived in 1777, just in time to participate in the important military operations centering around Brandywine and Germantown. His sojourn on Washington’s staff was especially significant to his development as a national leader after the war. It allowed him to associate with key officers of the Continental Army, men like Alexander Hamilton and James McHenry, who, beginning as military comrades, would become important political allies in the later fight for a strong national government. The opportunity to form such far-reaching political alliances seldom occurred for other Continental officers from the deep south.

In 1778 C.C. returned to South Carolina to resume command of his own regiment just as the state experienced a new threat from the British. His 1st South Carolina joined with other Continental and militia units from several states in a successful repulse of an invasion by a force of Loyalist militia and British regulars based in Florida. But disaster ensued when a counterattack bogged down before the Patriots could reach St. Augustine. The American Army suffered severe logistical problems and then a disintegration of the force itself, as senior officers bickered among themselves while disease decimated the units. Only half of the American soldiers survived to return home.

At the end of 1778 the British shifted their attention to the southern theater of operations. Their new strategy called for their regular troops to sweep north, while Loyalist units remained behind to serve as occupying forces. To frustrate this plan, the Continental Congress dispatched Major General Benjamin Lincoln to South Carolina to reorganize the army in the Southern Department. Lincoln placed C.C. in command of one of his Continental brigades. In that capacity Pinckney participated in the unsuccessful assault on Savannah by the Americans and their French allies in October 1779, and then in a gallant but equally unsuccessful defense of Charleston in 1780. The capture of Charleston gave the British their greatest victory, and in May Pinckney, along with the rest of Lincoln’s army, became a prisoner of war.

The victors made a distinction in the treatment of prisoners. They allowed the militiamen to go home on parole while they imprisoned the continentals. C.C. was one of the ranking officers in the prison camp established by Clinton on Haddrell’s Point in Charleston Harbor. There he played a key role in frustrating British efforts to subvert the loyalty of the captured troops, who suffered terribly from disease and privation. When an effort was made to wean C.C. himself from the Patriot cause, he scornfully turned on his captors with words that became widely quoted throughout the country: “If I had a vein that did not beat with the love of my Country, I myself would open it. If I had a drop of blood that could flow dishonourable, I myself would let it out.”

C.C. was finally freed in 1782 under a general exchange of prisoners. By that time the fighting had ended, but he remained on active duty until the southern regiments were disbanded in November 1783, receiving a brevet promotion to brigadier general in recognition of his long and faithful service to the Continental Army.

Pinckney turned his attention to his law practice and plantations at the end of the Revolution, seeking to recover from serious financial losses suffered during his period of active service. He continued to represent the citizens of the Charleston area in the lower house of the legislature, however, a task he willingly carried out until 1790. Once again he became active in the state militia, rising to the rank of major general and commanding one of South Carolina’s two militia divisions. During these years he also endured personal tragedy: his wife died in 1784, and he was wounded the following year in a duel with Daniel Huger, an event that would later lead him to advocate laws against dueling.

C.C. made no secret of his concern over what he saw as a dangerous drift in national affairs. Freed of the threat of British invasion, the states appeared content to pursue their own parochial concerns. Pinckney was one of those leaders of national vision who preached that the promises of the Revolution could never be realized unless the states banded together for their mutual political, economic, and military well-being. In recognition of his forceful leadership, South Carolina chose him to represent the state at the Constitutional Convention that met in Philadelphia in 1787. There he joined Washington and other nationalist leaders whom he had met during the Pennsylvania campaign. Pinckney agreed with them that the nation needed a strong central government, but he also worked for a carefully designed system of checks and balances to protect the citizen from the tyranny so often encountered in Europe. When he returned to Charleston, he worked diligently to secure South Carolina’s ratification of the new instrument of government. In 1790 he then participated in a convention that drafted a new state constitution modeled on the work accomplished in Philadelphia.

Retiring from politics in 1790, C.C. devoted himself to various religious and charitable works, including the establishment of a state university, strengthening of Charleston’s library system, and the promotion of scientific agriculture. He repeatedly declined President Washington’s offer of high political office, but in 1796 he finally agreed to serve as ambassador to France.

C.C.’s appointment signaled the beginning of one of the new nation’s first international crises. The French government rejected his credentials, and then in the so-called XYZ Affair the leaders of the French Revolution demanded a bribe before agreeing to open negotiations about French interference with American shipping. Exploding at this affront to America’s national honor, Pinckney broke off all discussion and returned home, where President John Adams appointed him to one of the highest posts in the new Provisional Army which Congress had voted to raise in response to the diplomatic rupture with France. As a major general, C.C. commanded all forces south of Maryland, but his active military service abruptly ended in the summer of 1800 when a peaceful solution to the “Quasi-War” between France and the United States was successfully negotiated.

Despite his earlier intention to retire, C.C. once again became deeply involved in national and state politics. He ran unsuccessfully for Vice President on the Federalist ticket in 1800 and was later defeated in presidential races won by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. He also served for two terms in the South Carolina senate. Until the end Pinckney remained a Federalist of the moderate stamp, seeking to preserve a balance between state and national powers and responsibilities. C.C. died on 16 August 1825, at Charleston, South Carolina and is buried at St. Michael’s Episcopal Church Cemetery, Charleston, South Carolina. His tomb bears an inscription that captures the essence of his loyalty to the highest national aspirations and standards of his period: “One of the founders of the American Republic. In war he was a companion in arms and friend of Washington. In peace he enjoyed his unchanging confidence.”

Richard Dobbs Spaight – Signer of the Constitution – North Carolina

Throughout his short life Richard Dobbs Spaight, who represented North Carolina in the Constitutional Convention, exhibited a marked devotion to the ideals heralded by the Revolution. The nephew of a Royal governor, possessed of all the advantages that accompanied such rank and political access, Spaight nevertheless fought for the political and economic rights of his fellow citizens, first on the battlefield against the forces of an authoritarian Parliament and later in state and national legislatures against those who he felt sought excessive government control over the lives of the people. The preservation of liberty was his political lodestar.

Throughout his short life Richard Dobbs Spaight, who represented North Carolina in the Constitutional Convention, exhibited a marked devotion to the ideals heralded by the Revolution. The nephew of a Royal governor, possessed of all the advantages that accompanied such rank and political access, Spaight nevertheless fought for the political and economic rights of his fellow citizens, first on the battlefield against the forces of an authoritarian Parliament and later in state and national legislatures against those who he felt sought excessive government control over the lives of the people. The preservation of liberty was his political lodestar.

Always an ardent nationalist, Spaight firmly supported the cause of effective central government. In this, he reflected a viewpoint common among veterans of the Revolution: that only a close union of all the states could preserve the liberties won by the cooperation of all the colonies. At the same time, Spaight believed that to guarantee the free exercise of these liberties, the powers of the state must be both limited and strictly defined. He therefore advocated constitutional provisions at the Convention that would protect the rights of the small states against the political power of their more populous neighbors, just as he later would fight for a constitutionally defined bill of rights to defend the individual citizen against the powers of government.

Richard Dobbs Spaight was born on 25 March 1758, at Newbern, North Carolina to Richard and Elizabeth Wilson Spaight. He was the great-great nephew of royal governor Arthur Dobbs. At the death of young Spaight’s father in 1763, Governor Dobbs and Frederick Gregg were appointed his guardians. (See http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr06-0313 for the appointment papers) His widowed mother married Thomas Clifford Howe but did not live long.

In 1767, at age nine, the orphaned lad sailed to Ireland to be raised and educated among his Anglo-Irish relatives (probably under care of the Dobbs family). This experience, which would include matriculation at the University of Glasgow, thrust the young colonial into the intellectual ferment swirling around the philosophers of the Enlightenment. These men taught that government was a solemn social contract between the people and their sovereign, with each party possessing certain inalienable rights. Like many of their American counterparts, the Anglo-Irish politicians considered themselves Englishmen with all the ancient rights and privileges such citizenship conferred and were quick to oppose any abridgment of those rights by Parliament. But while the Irish had been able to retain home rule, the American colonies were finding the power of their popular assemblies increasingly curtailed by a Parliament anxious to end an era of “salutary neglect.” The contrast was not lost on young Spaight. The Declaration of Independence found a sympathetic audience in Ireland, and Spaight’s loyalty to the Patriot cause only increased with the news in 1777 that North Carolina units had participated in the battle of Brandywine.