Category Archives: Code Talkers

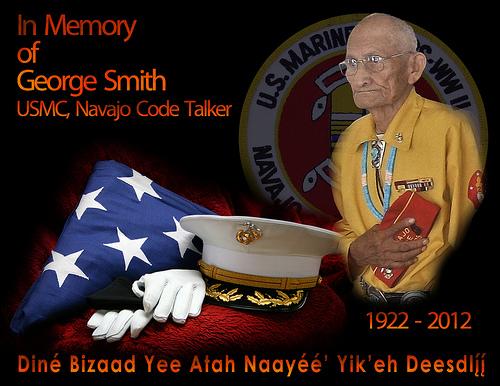

George Smith – United States Marine Corps – Code Talker

George Smith, 90, of Sundance, New Mexico, died 30 October 2012 at Gallup Indian Medical Center. He was born 15 June 1922 in Mariano Lake, New Mexico and was Salt People Clan, born for Black Streak Wood People Clan.

George Smith, 90, of Sundance, New Mexico, died 30 October 2012 at Gallup Indian Medical Center. He was born 15 June 1922 in Mariano Lake, New Mexico and was Salt People Clan, born for Black Streak Wood People Clan.

Grandson Merrill Teengar presented the eulogy by sharing moments from Smith’s life as a family man and Marine during the service at Rollie Mortuary.

“He loved his family and especially fond of the little ones,” Teengar said. “During his last visit to the hospital, he said ‘Don’t worry, everything will be OK. I lived my life. It’s time for me to go.'”

Like many Navajo boys, Smith spent his youth herding sheep with his brothers and spent time renaming the familiar landscape that comprise the back hills of Rehoboth and Breadsprings, N.M.

“He mentioned these days like they happened days before,” Teengar said.

Smith attended school in Crownpoint, which generated stories about school dances that he shared with his grandchildren.

“His grandchildren would tease him about the school dances he talked about,” Teengar said then added that his grandfather smiled ear to ear when watching the grandchildren imitate the dances.

His education continued at Wingate, where dancing was not allowed, Teengar said.

Smith enlisted in the U.S. Marines in 1943 and was trained as a rifle marksman then as a Code Talker and served in the battles of Ryukyu Islands, Saipan and Tinian and served in Hawaii, Japan and Okinawa.

He was one of three brothers who joined the military – his oldest brother Ray Smith joined the Army and his younger brother Albert Smith joined the Marines and also became a Code Talker.

Smith was 17 and Albert was 15 when they enlisted but changed their ages by two years.

He was honorably discharged 07 January 1946 with the rank of corporal.

After the war, he worked as a destroyer of old ammunition at the Fort Wingate Army Depot then as a mechanic at Fort Wingate Trading Post. “He loved fixing vehicles and did it well,” Teengar said then added that Smith taught his children and grandchildren the “ins and outs” of vehicle maintenance. “It came to the point where he could diagnose a vehicle problem while talking to someone on the phone,” Teengar said.

Smith eventually worked as an auto and heavy equipment diesel mechanic at Navajo Engineering and Construction Authority (NECA) in Fort Defiance then in Shiprock. He retired in 1995. Under NECA, he was sent to school in Peoria, Ill. and earned diesel mechanic credentials. Because Smith talked about his job with his family, his grandchildren gave him the nickname “NECA dude.”

He was a member of the Navajo Code Talkers Association and the Church Rock Veterans Organization. His favorite parade was the Gallup Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial where he enjoyed seeing familiar faces in the crowd.

Through his work with the Navajo Code Talkers Association, he traveled to many places including a revisit to Pearl Harbor and Saipan.

The funeral service, spoken in both English and Navajo, was a fitting homage to Navajo Code Talker George Smith, who delivered the code, based on the Navajo language that helped the United States defeat Japanese forces during World War II.

Corporal Smith was buried with full military honors at the Rehobeth Cemetery.

John Brown, Jr. – United States Marine Corps – Code Talker

John Brown Jr., 87, one of the original 29 U.S.M.C. WWII Code Talkers and a former Navajo Tribal councilman, passed on Wednesday morning, 21 May 2009.

John Brown Jr., 87, one of the original 29 U.S.M.C. WWII Code Talkers and a former Navajo Tribal councilman, passed on Wednesday morning, 21 May 2009.

Flags were ordered to be flown at half-staff by President Joe Shirley of the Navajo Nation in Brown’s honor.

“. . . with sadness, we heard of the passing of Mr. John Brown Jr., one of the original 29 Navajo Code Talkers and one of the Navajo Nation’s great warriors,” Shirley said. “For so long, these brave men were the true unsung heroes of World War II, shielding their valiant accomplishments not only from the world but from their own families. The recognition and acknowledgment of their great feats came to them late in life but, for most, not too late. These heroes among us are now a very precious few, and we, as a nation, mourn their loss. We offer our deepest condolences to the family of Mr. John Brown Jr.”

John Brown, Jr. was born 24 December 1921, in Chinle, near Canyon de Chelly to John and Nonabah Begay Brown. Brown attended Chinle Boarding School and graduated in 1940 from Albuquerque Indian School. He was playing basketball when he heard about the bombing at Pearl Harbor, said his son Frank Brown.

“Sometime after that he remembered a number of Marine recruiters started talking to the young Navajo boys,” Frank Brown said. Brown ended up going to Fort Wingate to the military installation. His father remembered being signed up, sworn in and given his physical right then and there, Frank Brown said. Brown was immediately sent to Camp Pendleton for basic training. “They weren’t allowed to go home to say goodbye to their family or write letters,” Frank Brown said. “At some phase in their basic training, they were taken into one big room and a commandant told them they were all there for a special reason, and they were to devise a code in their language,” Frank Brown said. “The boys were left there in the room and they didn’t know what the heck to do. But they devised the code using names of animals and mammals to describe what would go with the alphabet.”

That code consisted of translations for 211 English words and was later expanded to 411 words, according to the president’s office. The code also included Navajo equivalents for the letters in the English alphabets so the Code Talkers could spell out names and locations. The  code and the Code Talkers would help end World War II.

code and the Code Talkers would help end World War II.

Navajo Code Talkers participated in battles in the Pacific from 1942 to 1945. Frank Brown said his father served in four major battles at Tarawa, Saipan, Tinian and Guadalcanal. The code was not declassified until 1968.

Brown was one of the original 29 Code Talkers presented with the Congressional Gold Medal by President George W. Bush on July 26, 2001 — 56 years following World War II.

“It is, indeed, an honor to be here today before you, representing my fellow distinguished Navajo code talkers,” Brown said at the presentation at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. “Only destiny has demanded my presence here, for we must never forget that these such events are made possible only by the ultimate sacrifice of thousands of American men and women who, I am certain, are watching us now. And yes, it is fitting, too, here in the Capitol Rotunda – such a historic place, where so many heroes have been honored. I’m proud that the Navajo Code Talkers today join the ranks of these great Americans. I’d like especially to thank Senator Bingaman and all of work that he has given to make this occasion possible, to recognize the code talkers.”

“I enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1942, not to become a Code Talker — that came later — but to defend the United States of America in the war against the Japanese emperor.”

“My mother was afraid for my safety, so my grandfather told her to take one of my shoes, place an arrowhead in it, take it to the mountain called Two Little Hills, and go there every day to pray that I would remain safe. Maybe she was more successful than she imagined because the Marine Corps soon had the Navajo Marines develop a secret code using our language. My comrade and I volunteered to become Navajo radio operators, or Code Talkers,” Brown said at the presentation.

“Our precious and sacred Navajo language was bestowed upon us, not a nation, but a holy people. Our language is older than the Constitution of the United States. I’m proud that, at this point in American history, our native language and the code we developed came to the aid of our country, saving American lives and helping the other U.S. armed forces ultimately to defeat the enemies.”

“After the original 29 Code Talkers, there are just five of us that live today: Chester Nez, Lloyd Oliver, Allen Dale June, Joe Palmer and myself. We have seen much in our lives. We have experienced war and peace. We know the value of freedom and democracy that this great nation embodies. But our experience has also shown us how fragile these things can be and how we must stay ever vigilant to protect them, as Code Talkers, as Marines.

“We did our part to protect these values. It is my hope that our young people will carry on this honorable tradition as long as the grass shall grow and water shall flow,” Brown said.

“Mr. President, we four original code talkers present this day, including the families of my comrades who aren’t able to be here with us, are honored to be here to receive this award. Thank you,” Brown said.

President Richard Nixon awarded Navajo Code Talkers a special certificate in appreciation for their patriotism, resourcefulness and courage in 1971. They were included in the Bicentennial Parade in Washington July 4, 1976.

The U. S. Senate passed a bill declaring August 14 National Code Talkers Day in May 1982.

Frank Brown said his father lived a hard life, first training as a welder, then becoming a journeyman and master carpenter and cabinetmaker. He was one of the veterans who returned to Navajo land and helped to build the Navajo government by serving as a member of the Navajo Tribal Council from 1962 to 1982. He also served three terms as Crystal Chapter president. “He was always active in politics,” Frank Brown said. “He was a wonderful speaker.”

Brown began a second career as a traditional counselor for the tribe’s Division of Social Services, driving 130 miles to Chinle and back each day. After that, he went on a lecture tour speaking about the Navajo Code Talkers around the country and becoming active in the Navajo Code Talkers Association, his son said. “Dad was also a traditional practitioner, constantly learning the traditional way of life but at the same time he was always active in the Mormon Church,” Frank Brown said.

Brown is survived by his wife Loncie Polacca Brown and his children Dorothy Whilden, Preston Brown, Everett Brown, Virgil Brown and Frank Brown. His other children were the late Dale Brown and the late Ruth Ann McComb.

He is buried at Crystal Cemetery, San Juan County, New Mexico.

Dan Akee – United States Marine Corps – Code Talker

Dan Akee, of the Kiyanni and Ashihii clans, was born in Coalmine Canyon in November 1922. He grew up in the Coalmine Mesa area. He started school in 1928 at an early age at the Tuba City Boarding School. Akee withdrew from school shortly after he started for medical reasons and went to a convalescence home in Kayenta, Ariz. to recover from tuberculosis. There he taught himself and reached a 10th grade level equivalent.

Dan Akee, of the Kiyanni and Ashihii clans, was born in Coalmine Canyon in November 1922. He grew up in the Coalmine Mesa area. He started school in 1928 at an early age at the Tuba City Boarding School. Akee withdrew from school shortly after he started for medical reasons and went to a convalescence home in Kayenta, Ariz. to recover from tuberculosis. There he taught himself and reached a 10th grade level equivalent.

Akee enlisted in the United States Marine Corps in 1943, shortly after the outbreak of WWII. Akee trained as a code talker and was detailed to the 4th Marine Division, 25th Regiment. From 1943-45, Akee took part in some of the most ferocious fighting in the Pacific theater. He participated in the Marshall Islands, Saipan, Tinian and Iwo Jima campaigns.

As a code talker, Akee transmitted and received messages in coded Navajo, a code that was never broken. During battle, Akee was often on the front lines, receiving communication for his regiment. Especially at Iwo Jima, he lost many of his regiment and friends. Some years ago, the Retired Sergeant Major received the Congressional Silver Medal of Honor for his service.

After the war, Akee retired to civilian life with a rank of Sergeant Major, the highest rank for a non-commissioned Marine officer. He went back to high school at the Sherman Institute in Calif. but did not get a high school diploma, because of post war stress trauma. According to Akee, he recovered from the trauma with the help of Navajo Way and Christianity. He worked on the railroad and in a uranium ore processing plant. In 1967, he became an interpreter with Tuba City Hospital’s mental health department where he retired in 1988 after 21 years of service.

After delivering a prayer of remembrance in Navajo, Akee outlined the skills needed to memorize the approximately 555 Navajo words in the highly classified system. The code terms were designed to communicate locations and information of strategic importance during the Second World War. Navajo words, he said, were integrated to represent approximately 450 military terms not in the traditional language, such as submarine and dive-bomber.

The Tuba City resident explained it took five months to memorize the code, which remained top-secret until declassified in 1968. He emphasized the importance of indigenous language preservation and how the code was used to save many lives on both sides, and especially hasten the end of the war.

The approximately 450 Navajo Marines were not allowed to discuss their Signal Corps role in World War II until the 1990s. In 2001, they received Congressional Medals for service to their country.

School officials said the honorary high school diploma is long overdue and recognizes Akee’s achievement as a code talker and his outstanding and tireless lifetime of service to the Navajo people and the United States.

Dan Akee and his wife have 12 children. As of 2011, Sergeant Major Dan Akee and his wife had 73 grandchildren.

Chester Nez – United States Marine Corps – Code Talker

Twenty-nine Navajo Marines created an unbreakable military code used during World War II. Memories of those glory days are fading, and Chester Nez is the last living original Code Talker.

Twenty-nine Navajo Marines created an unbreakable military code used during World War II. Memories of those glory days are fading, and Chester Nez is the last living original Code Talker.

All the rest of the U.S. Marines who created the first unbreakable code that baffled the Japanese during World War II have died. Nez has been asked to tell his own story many times. When he tells it in English, he refers to pre-written answers his family keeps on a sheet of notebook paper. The questions are almost always the same. When his memory fails him — at 93, Nez is now an old man — he looks off into the distance. “Ask my son,” he says.

But when he speaks in Navajo, in the vivid light of the late afternoon, the colors of his memories are saturated, the edges sharp.

He remembers the words that helped slay the enemy even as they pierced his own sacred beliefs.

He remembers the words that helped protect him on the fields of battle.

And he remembers a full life. There is so much more to remember about Iiná, life.

Summers spent chasing after lambs and goats among the high desert scrub southwest of Gallup, N.M.

The school on the Navajo Reservation. A Marine Corps recruiter in a crisp uniform. A bus trip to California.

The room at Camp Elliott where Nez would help devise the simple code.

A war to fight in a faraway land.

A home to return to.

Demons to bury.

A family.

A career.

A medal.

“Chéch’iltah déé’ naashá. I’m from Chi Chil Tah, among the oaks, in Jones Ranch, N.M,” he introduces himself in Navajo. “I belong to my mother’s matriarchal clan Black Sheep, and I’m born for my father’s clan, the Sleeping Rock people.”

Ti’ níléí dah’azká biláahdi hat’íí hóló “Let’s go see what’s behind that mesa.”

The 1930s were the heyday of Navajo shepherds. Most families who lived on the reservation tended to a flock. A large flock was a sign of wealth and success.

But in 1934, the federal government, as trustee, imposed a livestock-reduction policy because sheep and cattle were destroying the land through overgrazing. Navajo leaders and families fought the government, but in the end, many had their animals confiscated and sold, slaughtered or herded off canyon cliffs to their deaths.

Dine Nez was a shepherd on the high mesa of the reservation near Jones Ranch, where rolling hills of piñon, ponderosa, juniper and oak are divided by lush meadows and deep canyons. As the herds were thinned, he began to see that his son, Chester, would have to learn to make a living in the White man’s world.

He enrolled his son in a government-run school in Fort Defiance, in northeastern Arizona, far from the grazing lands of their home.

When Chester Nez reached high school in the early 1940s, educators moved some students to Tuba City Boarding School, on the far western portion of the reservation north of Flagstaff. The Department of the Army operated the school. The boys learned English in the schools and grew up far from their families. Still, while the land was vast, they knew little of the world beyond the sacred mountains that framed their home.

Since ancient times, Navajos have looked to four sacred mountains to define the boundaries of their world — Blanca Peak in Colorado, Mount Taylor in New Mexico, the San Francisco Peaks in Arizona and Hesperus Peak in Colorado. For Nez, language and life had always been defined by the images and formations of the land around him.

Then, on a spring day in 1942, U.S. Marines came to the boarding school, looking for Navajo boys.

Four months earlier, 3,000 miles away, a sky full of planes had unleashed fire on Pearl Harbor. The reservation was quiet, but the world was at war. The military, ferrying troops to battle sites across the Pacific, was urgently seeking an undecipherable code to transmit classified information. It had attempted to use various languages and dialects as code, but each was quickly cracked by cryptographers in Tokyo.

Philip Johnston, a former Army engineer and the son of Presbyterian missionaries who had lived on the Navajo reservation, proposed an idea: Try using the Navajo language. Written record of it was scarce. Its syntax and grammar were elaborate. The spoken language used tones that were difficult for an untrained ear to understand. The language might prove harder for the enemy to decipher.

So that day in 1942, the Marine recruiters in red and white uniforms with shiny buttons showed up at the school’s Old Main. They were seeking smart Navajo boys who spoke their native language and understood English. Nez longed to see life beyond the Navajo Reservation.

“I told my buddy Roy Begay, ‘Let’s go see what’s behind that mesa,’.” Nez remembered. “We said, ‘táá ako’nihíí d’odoo,‘ We agree, and we will join, too.’,”

A. Wol-la-chee. Ant. B. Shush. Bear. C. Moasi. Cat. D. Be. Deer. E. Dzeh. Elk. F. Ma-e. Fox. When school finished in 1942, a charter bus full of young Navajo men, including Nez and Begay, pulled out of Fort Wingate, east of Gallup, N.M. The bus was headed for California with enlistees on a secret mission. The men said farewell to their four sacred mountains. They left behind a simpler life on the reservation for the uncertainties of war.

Nez remembers losing his jet-black hair to a barber’s razor shortly after he arrived in San Diego for boot camp. “I touched my head. It was sleek as the canvas pants I wear,” Nez said, sliding his hand along the fabric of his pant leg.

The 29 men became the all-Navajo 382nd Marine Platoon.

Their first task was learning the military’s communication system. Next, they were asked to build a code using Navajo words. The code would have to be accurate, consistent, simple and easily memorized. One soldier suggested creating an alphabet using Navajo words, while another proposed using native words for animals, plants, neighboring tribes or weapons, according to Sally McClain, author of “Navajo Weapon.” McClain collected first-person accounts from several of the original Code Talkers. Nez said words for the code came from everyday words used on the reservation, such as lamb, nut, quiver, cross and yucca.

The men easily attached familiar words to letters to create a code alphabet.

“A.” Wol-la-chee. Ant.

“B.” Shush. Bear.

“C.” Moasi. Cat.

“D.” Be. Deer.

“E.” Dzeh. Elk.

“F.” Ma-e. Fox.

So the word “enemy,” E-N-E-M-Y, would be Dzeh — Nesh-chee — Dzeh — Na-as-tsosi — Tash-as-zih.

More challenging was devising a code to represent military equipment such as ships, airplanes or the ranks of officers. The men struggled to describe war objects they had never seen during their lives on the reservation.

“Major general.” So-na-kih. Two stars.

“Reconnaissance.” Ha-a-cidi. Inspector.

“Artillery.” Be-al-do-tso-lani. Many big guns.

Nez has long forgotten which words he suggested. “Doo bénáshniihda,” I can’t remember, he said, closing his eyes and searching his memory for answers. He does remember another challenge of creating the code. As the system took shape, each Navajo word took on a new meaning. But Navajo words carried their own significance. Using them in battle, Nez feared, would bring him harm.

Ách’ááh tsodizin A shield made of prayer

In Navajo culture, elders impress upon their children that the spoken Navajo word is potent. Words uttered in a harmful way bring harm to the speaker or his family, they say. A child growing up on the reservation in the 1930s would have understood this. Nizaad baa’ áhályá, he would be told. Be cautious of how you speak. Saad, words, carry unseen power.

Nez knew the code was meant to help confound the enemy. But that would mean using the language, his words, to bring harm. He turned to his family. The words carried unseen power, but they were also powerful enough to offer him a shield. Historically, Navajo words used by a soldier in war could be protected by a religious ritual called ách’ááh tsodizin — a shield made of prayer. Such a shield was worn by Naayéé’ Neizghání, Monster Slayer, a Navajo hero who, according to belief, killed people-eating giants. Other Navajo soldiers had prayers conducted for them by tribal medicine people on the reservation before they shipped out.

But Nez could not return to the reservation. The original 29 Code Talkers were not allowed to leave the base. Their secret code had to be protected.

At Camp Pendleton, in California, Nez packed up his Marine uniforms, his fatigues, and placed them in the mail.

Soon the package reached his father’s home on the reservation.

Dine Nez gathered up the package and had a medicine man perform a ách’ááh tsodizin over them. Then he sent the clothes back to his son.

The creation of the code was only the first part of the 382nd Marine Platoon’s orders.

Once the encryption system was written, the men would go to war. In August 1942, Chester Nez put on his uniform and boarded a ship for New Caledonia.

As he went, he said, he carried the power of the prayer shield to protect him from the harm that would be inflicted.

Anaa’í. Enemy. Nááts’ósí. Japanese. Be’eldooh alháá dildoni. Machine Gun. Nish’náájígo. Dahdikadgo. On your right flank. Diiltááh. Destroy. The men of the 382nd Platoon sent messages informing U.S. command of Japanese tactics, strategy and troop movement in battles at Iwo Jima, Peleliu and Guadalcanal. Nez and his friend Begay were part of an assault team and helped gather intelligence.

They would land on beaches, go behind battle lines and relay back information about the enemy. The group worked in pairs, carrying 30 pounds of radio equipment. Using walkie-talkies, the men sent messages in Navajo and a Navajo soldier on the other end translated. The language was familiar, but the reality of war was very far away from the reservation.

Nez shakes his head to make the vision disappear. “Tábaahjii’ nihil nida’iiz’éél, Nááts’ósí nidaaztseedgo ákóó nideeztaad. We would land on the beaches, which were littered with dead Japanese bodies,” Nez says in Navajo. “My faith told me not to walk among the dead, to stay away from the dead. But which soldier could avoid such? This was war. War is death. I walked among them.” The battles thundered with the sounds of artillery. And they were so far away from their dry Navajo lands.

“I remember sitting in the foxhole with Roy and rain poured,” Nez said.

Other groups of Navajos would eventually become Code Talkers as well. By war’s end, there were about 420 Code Talkers, and the code had expanded to more than 500 words.

But Nez’s platoon was the first.

Nez said he felt safe during the war because of the shield of prayer. He believes it is the reason he survived.

Ya’at’eeh shíye’ “Hello, my son.”

When Nez finished his military service in 1945, he jumped off the bus in Gallup, N.M., harboring a secret. Like the other Code Talkers, he had been ordered to keep silent about the Navajo code he helped create. He didn’t breathe a word about it for more than 20 years.

Unlike jubilant celebrations in metropolitan cities for returning American troops, Nez’s Navajo community of Chi Chil Tah, 23 miles southwest of Gallup, was subdued. He hitchhiked to Cousins Brothers Trading Post, and the store’s owner dropped him off near his father’s hogan. For Nez, there would be no ticker-tape welcome, just the quiet of the reservation and his father’s home. He admired his father deeply. His father had raised him and eight other siblings. Their mother had died when Nez was young. But as he returned home, he remembered his mother, too, whom he would never see again.

He reached the hogan, and his father appeared.

The man reached out and shook Nez’s hand.

“Ya’at’eeh shíye,‘.” he said.

The words mean “Hello, my son.” But in Navajo they mean much more. The message brimmed with a father’s affection, recognized a son’s place in an extended family and spoke to a trusting father-son relationship.

Six decades later, Nez’s eyes tear up when he remembers the words. “To say something like that, which is very, very close to you, is very, very moving, if not uncomfortable,” Nez said. “It’s real sad to come home and see your parent.” Soon after his son’s return, Dine Nez hired Hastiin Tsé Lichíí’ Nééz, Tall Red Rock, to perform the Enemy Way, a religious ritual meant to bring peace to a returning warrior by re-enacting a war party. It’s believed the rite cleanses a soldier of war’s taint and heads off post-war ailments. It is still practiced today for returning soldiers. When Tsé Lichíí’ Nééz repeated the final prayers during the ceremony for Nez, the grief, trauma and stress of war was bundled up, buried in the ground, and with a shot of a gun, symbolically returned to the earth. The code was included in the memories of the war that were to be forgotten.

“I felt better. … I felt I was like a new man,” Nez said. “I forgot all the things that I went through during World War II.” People inquired of his whereabouts in the Pacific, Nez said, but no one probed him about his role in the war. Shil nilí “I appreciate it.”

Nez finished high school at Haskell Indian Nations University in Lawrence, Kan., then studied fine arts at the University of Kansas.

He stayed in the Marine reserve and served in the Korean War, returning again to the reservation, where he married and raised a family. For two decades, Nez painted murals at Raymond G. Murphy VA Medical Center, in Albuquerque, where he retired in 1974.

Nez returned to his roots, once more, to Chi Chil Tah where he cared for a sibling and a flock of sheep. He moved in with his son’s family in Albuquerque in 1990.

More than a half-century after he was discharged from the Marines, Nez met President George W. Bush.

On July 26, 2001, Bush handed Congressional Gold Medals to five living original Navajo Code Talkers who had come to Washington, D.C. The medal is an expression of national appreciation for distinguished achievements and contributions. “President Bush was the nicest man I met,” Nez said. “He seemed very glad to shake hands with the Code Talkers. I thought we deserved the medal.” Only long after the Enemy Way ceremony had buried his memories would Nez share his stories. He wanted people to know what he and the others did in the war.

After all, noted his son, Michael, the story was kept a secret for so long.

It is an obvious point of pride for the former Marine.

Baa’ ahééh nisin, “I’m pleased and grateful about it,” Nez said. Shil nilí, “I appreciate it.” J’o ako téé’go nise báá “That’s my journey to war and back.”

Nez, who has had a long life with many children, is wealthy according to Navajo beliefs. The father of six children, he has nine grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren. He has outlived all but two of his children and shares a home with Michael and his family.

Today, Nez uses a wheelchair. Diabetes has claimed his legs. Time has dulled his hearing.

Nez tells his story seated in the living room of his son’s home. Behind him, the wall is covered with family portraits. The afternoon sun glows through the window.

He wears the recognizable uniform of the Code Talkers, brown pants that symbolize the earth, gold shirt for the color of corn pollen and a red cap that represents the tint of blood.

Asked how he wants to be remembered, Nez said he wants his legacy to be when his country, America, called on him. Of the 29 original Code  Talkers, he’s the only one left, and he struggles to convey how he feels about being the last living symbol. Proud, patriotic, happy to be among his family.

Talkers, he’s the only one left, and he struggles to convey how he feels about being the last living symbol. Proud, patriotic, happy to be among his family.

J’o ako téé’go nise báá, “That’s my journey to war and back,” he said.

Soft evening twilight moves over the Sandia Mountains east of Michael Nez’s home. The gold in Chester Nez’s shirt deepens. The faces in the family photographs are no longer sharply defined. Darkness creeps into the living room. Nez wheels himself into the bedroom. A grandson prepares him for bed.

Mr. Nez passed earlier this year – 2014.

Joe Palmer a.k.a. Balmer Slowtalker – United States Marine Corps – Code Talker

Joe Palmer was born Balmer Slowtalker on 10 March 1922 to Judge and May Slowtalker in Leupp, Arizona.

Joe Palmer was born Balmer Slowtalker on 10 March 1922 to Judge and May Slowtalker in Leupp, Arizona.

As a Marine in WWII Palmer and 28 other Code Talkers used their native language to transmit military messages on enemy tatics, Japanese troop movements and other battlefield informatian by telephone and radio.

He was honorably discharged in January of 1946. During his service he received the Purple Heart, 4 Bronze Star Medals and a Presidential Citation. In July of 2001 he received the U.S. Congressional Gold Medal for his service as one of the original 29 Navajo Code Talkers. He was a retired lineman for the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

According to the Naval Historical Center in Washington, the Navajo Code Talkers took part in every assault the Marines conducted in the Pacific from 1942 to 1945 and were praised for their skill, speed and accuracy. Their work was impossible for the enemy to decode. After the war, Palmer and the others were told to keep the Navajo code a secret. Even after the information was declassified in 1968, they were reluctant to discuss it or take credit for their deeds.

Palmer, 84, Of Yuma, AZ, died on Saturday, 18 November 2006 at the VA Medical Center in Tucson. He leaves his wife, Flora Nejo Palmer; son, Kermit (Earlena); granddaughter, Cejae; brothers, Tom, Thomas (Carol), Kee (Susie), Keeteddy (Sandra), John (Zannie) and Jimmie; and sisters, Betty Slowtalker and Bessie Scott. Joe was preceded in death by his father, Judge Slowtalker and mother, Mary. He is buried at Desert Lawn Memorial Park, Yuma, AZ

Lloyd Oliver – United States Marine Corps – Code Talker

“Gentle, kind and humble.” That’s how Lloyd Oliver struck many people upon their first meeting with him. Oliver, one of just two of the remaining original 29 Navajo Code Talkers, answered the final reveille last week far from his birthplace of Shiprock, Arizona

“Gentle, kind and humble.” That’s how Lloyd Oliver struck many people upon their first meeting with him. Oliver, one of just two of the remaining original 29 Navajo Code Talkers, answered the final reveille last week far from his birthplace of Shiprock, Arizona

Oliver, 87, died 16 March 2011 of pancreatitis in Avondale, Ariz., near where he had made his home with his second wife, Lucille.

Oliver was born April 23, 1923, into Bit’ahnii (Folded Arms Clan), born for Kinlichíi’nii (Red House Clan). His chei was Naakaii Dine’é (Mexican People Clan) and his nálí was Tódích’íi’nii (Bitter Water Clan).

He grew up in Shiprock, where he graduated from Shiprock Agricultural High School in 1941. A year later, at age 19, he enlisted in the Marines and became one of the first of the elite group later named the Navajo Code Talkers. He didn’t set out to be a hero, said Oliver’s nephew Lawrence Oliver, whose father Willard also was a code talker. “I was sitting with my dad once and asked him if he knew why Uncle Lloyd enlisted,” Lawrence said. “(Willard) said that (Lloyd’s) girlfriend was mad at him.” Willard Oliver died in 2009.

Lloyd Oliver served in the Marines until 1945, when he was discharged with the rank of corporal. More than five decades would pass before his family knew how pivotal he had been in winning the war in the Pacific.

Oliver, who preferred not to have a hearing aid, spoke audibly but his words could be difficult to understand. The Code Talkers were instructed not to discuss their roles and felt compelled to honor those orders even after the code was declassified in 1968. His military records make a single mention of “code talker.” He otherwise was listed as “communication duty,” or “communication personnel.”

Years later, his hearing remained impaired because of gun blasts and other explosives during the war. He rarely brought up his time as a Code Talker, but his eyes gleamed when holding a picture of himself in his uniform. He kept a Marine cap and a U.S. flag displayed on his bedroom walls in the home he shared with his wife on the Yavapai Apache Reservation.

Like thousands of other GIs, Oliver returned to his hometown, married and had a child. Things didn’t work out, however, and he moved to Phoenix to find work.

There he learned silver and metalsmithing, and developed a distinctive style as a jewelry maker. He supported himself selling his work through Atkinson’s Trading Post in Scottsdale, Ariz., continuing well into his 70s.

Oliver was known for being industrious and self-sufficient. His grandson, Steven Lloyd Oliver, recalls a visit the two made to New York City in 2009, where the code talkers had been invited to take part in the Veteran’s Day parade.

2009, where the code talkers had been invited to take part in the Veteran’s Day parade.

Oliver’s death meant that only one of the original 29 Navajo Code Talkers survived — Chester Nez of Albuquerque, N.M. The 87-year-old Oliver died at a hospice center in the Phoenix suburb of Avondale where he had been staying for about three weeks, his nephew, Lawrence, said Friday.

“It’s very heartbreaking to know that we are losing our Navajo Code Talkers, and especially one of the original 29 whose stories would be tremendously valuable,” said Yvonne Murphy, secretary of the Navajo Code Talkers Foundation. Hundreds of Navajos followed in the original code talkers’ footsteps, sending thousands of messages without error on Japanese troop movements, battlefield tactics and other communications critical to the war’s ultimate outcome. The Code Talkers took part in every assault the Marines conducted in the Pacific.

Navajo President Ben Shelly called Oliver a “national treasure” and ordered flags lowered across the reservation in his honor.

Arthur Hubbard, Sr. – Navajo Code Talker – United States Marine Corps

It was a moving final farewell to one of Arizona’s most distinguished citizens as funeral services were held for 102-year-old Arthur Hubbard, Sr. — a Navajo code talker instructor who was instrumental in helping win World War II for the allies. Mr. Hubbard was a man of many accomplishments.

It was a moving final farewell to one of Arizona’s most distinguished citizens as funeral services were held for 102-year-old Arthur Hubbard, Sr. — a Navajo code talker instructor who was instrumental in helping win World War II for the allies. Mr. Hubbard was a man of many accomplishments.

The memorial service at Pinnacle Presbyterian Church in Scottsdale was a time to be sad and reflective, but also to appreciate a life well-lived, for Hubbard Sr. lived a very long time and did some extraordinary things. “We should all celebrate… If you are over 100 years old, you have lived your full life and he has done that,” said Navajo Nation President Ben Shelly.

Hubbard was born on January 23, 1912 in the Tohono O’odham Nation in Topawa, Arizona about three weeks before Arizona became a state. He grew up in Ganado, Arizona part of the Navajo Nation, and studied at the University of Arizona. He was the leader of a Navajo tribal band, as a trombone player and singer.

From 1939 to 1945 Hubbard voluntarily served in the U. S. Marine Corps. During World War II, he was a Navajo Code Talker instructor training over 200 men to transmit coded messages using the Navajo language. After his military duties, the then Governor Jack Williams appointed him Director of Indian Development District of Arizona. In 1972 he became state senator in Arizona, serving for 12 years until 1984. This made him the first Native American senator in the Arizona State Legislature. His other work included serving as a water rights advisor to the Tohono O’odham Nation, and as a Navajo culture and language instructor at Arizona State University. He also played an important part in the establishment of Diné College (originally known as Navajo Community College), which was the first college established within the Navajo Nation.

Hubbard was inducted into the Arizona Veterans Hall of Fame and the Arizona Democratic Party Hall of Fame. He received the Navajo Code Talker Congressional Silver Medal in 2000. A 2011 Arizona Senate resolution listed Hubbard as the first Native Americans to serve in the Senate. Tribal leaders called Hubbard a powerful advocate for American Indians.

“The talks and experiences of his teachings were to each and every one of us. It is a loss, but yet we hold that dear and continue forward,” said Hubbard’s nephew, Gordon J. Smith. Through it all, Hubbard remained humble, saying of each accomplishment: “There was a job to be done and I did it.”

He died at age 102 on February 7, 2014, in Phoenix, Arizona. On his death, flags across the Navajo Nation were flown at half-staff in his honor. He was buried at the National Veterans Memorial Cemetery, 23029 N. Cave Creek Rd., Phoenix, AZ.

Recent Comments